Two Pandemics: From the Past to the Present

March 23, 2021

Every morning at 7:45 a.m., Sofia Llevat ’22 wakes up to her phone alarm. She stands in front of her closet, contemplating what to wear to virtual school. While Llevat resists the urge to stay in her pajamas, she still can’t remember the last time she wore a pair of jeans. From there, she sits at her desk for the remainder of the day, besides exercise and food breaks. The next day, it happens all over again.

“[Staying motivated has] been difficult,” Llevat said.

For Llevat, that silver lining has come in the form of finding ways to keep busy. 102 years ago, prior to the merger in 1991, students at both the Harvard Military School and the Westlake School for Girls found themselves in a similar situation. The first cases of the H1N1 virus pandemic, colloquially known as the Spanish Influenza, emerged in Los Angeles during the fall of 1918. Shortly after, schools were closed for approximately eight weeks.

Students follow the tradition of community service

While the influenza spread throughout the states, World War I was simultaneously coming to a close abroad. Although women were precluded from combat during WWI, Westlake girls were on the front lines during the influenza. The students raised money, crocheted bandages and worked as nurses. Many Harvard Military School alumni directly advanced into the War as soldiers. Flash-forward a century later, students like Kendra Ross ’23 are still actively engaged in current affairs.

“The pandemic definitely heightens the importance of giving in times of hardship,” Ross said. “[It] highlights, even more, the circumstances we’re living in and the amount of help needed [within] the community.”

Following in the history of Westlake service, Ross, in tandem with her sister Julianna Ross ’22, has organized COVID-19-safe community service opportunities, such as a toy drive for orphaned children.

Jessica Wahl draws comparisons between the 1918 and 2020 pandemics

Upper School Librarian Jessica Wahl has followed history in a different way. As a silent film lover, her extensive research on the subject led her to create an Instagram account called “Silence is Platinum” in 2010 to feature lesser-known silent film performers.

In her research of the early 20th century, she found that while other age groups were not spared, the influenza overwhelmingly targeted young adults, killing many up-and-coming silent film performers. Upon further investigation into the impacts of the 1918 pandemic, the circumstances became increasingly familiar, she said.

“Even though [the Influenza of 1918] was so long ago, we’re looking at a lot of the same stuff today,” Wahl said. “It would be interesting if we did have people that survived the pandemic alive today to talk about it, but we don’t. It’s just a matter of looking back and seeing how things fared then and how we can apply it to what’s happening now.”

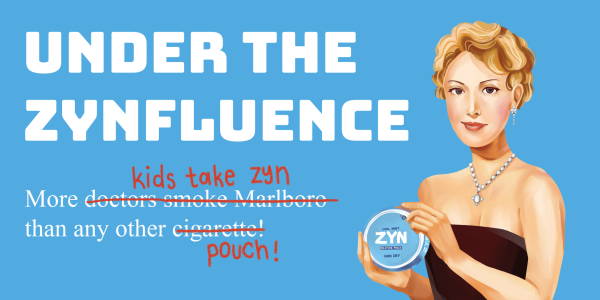

Wahl said she equates the satire she discovered in poetry and songs to contemporary memes and the war-related volunteer work to recent protests and community service.

“Reading through these articles from like 100 years ago, where it talks about the importance of wearing a mask and talking about how theaters and restaurants closed, it’s so parallel,” Wahl said.

Alexis Arinsburg shares her findings on the 1918 pandemic’s impact on the Harvard Military School and the Westlake School For Girls

Last May, archivist Alexis Arinsburg ’98 began researching the influenza’s impact on both Harvard Military School and Westlake School for Girls. After sifting through Harvard’s school paper, The Sentinel, and Westlake’s Vox Puellarum, which is Latin for “The Voice of the Girls,” Arinsburg discovered several references to the influenza.

Although the case count at the Westlake School for Girls is unknown, The Sentinel recorded that there were 45 cases among the boarders at Harvard Military School. All but two students recovered.

“The cases are all light—scarcely more than severe colds, but they are so numerous that I considered it unwise to keep the school open the remainder of the week,” Headmaster of Harvard Military School Robert B. Gooden told The Los Angeles Times on Oct. 11, 1918. “All of the boys are recovering. There are 290 pupils enrolled but most of them are boys who reside at home. The sickness broke out among those who board at the school.”

Carlton Canfield, a 17-year-old student from a well-known family in Santa Cruz, died from the virus on campus after it developed into a severe case of pneumonia. It is unknown whether or not his parents made it to his bedside in time to say goodbye. An article from the Santa Cruz Evening News, published Oct. 15, 1918, described the funeral service, noting the exquisite floral offerings and “two appropriate duets.”

“His sudden death will be a shock to scores of girls and boys in this city and the universal sympathy of the community will be extended [to] the parents in their great grief,” wrote the Santa Cruz Evening News on Oct. 12, 1918

In both pandemics, the school invests in safety precautions and adjusts accordingly

During the 1918 Influenza outbreak, the Harvard gym was converted into a hospital with a doctor accompanied by 12 full-time nurses. In addition, Harvard Military School built a hospital at a separate location with a resident nurse to address any potential cases.

According to an email from President Rick Commons sent Jan. 8, the school hired two registered nurses on each campus and invested in PPE supplies, HVAC upgrades, improvements to classroom technology and a contact tracing app.

“We didn’t miss a beat,” Arinsburg said. “Two days later, everyone’s back online. It was more disruptive back then because we couldn’t continue with academics, the way that students are able to today. So much of their social life was upended, and in sports, they lost a whole season.”

Harvard Military School made up the lost time by holding school until 1 p.m. on Saturdays and omitting winter and spring break. The suspension of athletics meant that Harvard forfeited its football season in favor of basketball—a decision that was backed by the city.

While the school was able to replicate many aspects of in-person school virtually during the current pandemic, two seasons of athletics were indefinitely postponed or canceled. Llevat, who plays field hockey, said she predicted losing the upcoming season of field hockey because of how difficult it was to practice under the safety guidelines when the school opened for athletics.

“I was excited because I love my team, and I was so happy to play with them again after a whole year,” Llevat said. “There were practices in person at school socially distant, which is very difficult to do with a sport like field hockey. It was really hard to adjust to practicing a sport that’s pretty face-to-face.”

Arinsburg shares her takeaways from the school newspapers

Arinsburg said both school papers painted a rosy picture of the 1918 Influenza’s impact. And while the current pandemic isn’t over yet, she said she is encouraged by their upbeat reflections.

“As summer comes and books are laid aside for a few weeks of recreation, I am sure that we can all look back and say that this has been a very happy and successful year,” Lillian Miller, a member of the Westlake School for Girls Class of 1919, wrote in Vox Puellarum. “It was not without interruption, however, for we were obliged to lose seven weeks of lessons in the first semester during the quarantine. But with the assistance of our teachers and greater personal effort, we succeeded in covering the ground by the beginning of the second term. So we find that bad beginnings usually have good endings.”