Driving Dangerously

April 24, 2013

As the end of the school day rolls around, Susie* ’14 and her two friends head towards the school parking lot, piling into her gray Jetta after an argument over who called “shotgun” first.

They roll down their windows as they pull out of the school driveway, unconcerned with the driving law that they are breaking.

According to the California Vehicle Code, drivers under 18 who have had their license for less than a year cannot carry any passengers under 20 or drive between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. without an adult over 25 in the car.

This law, however, doesn’t stop a large fraction of the student body from legally driving their friends.

“I drive people all the time,” Susie said. “My parents don’t really allow it, seeing as they’re not big fans of me breaking the law, but I don’t tell them. If I’m out all day, how are they ever going to find out I had other people in my car?”

Susie says she doesn’t hesitate to give a friend a ride and generally ends up with an underage passenger in her car once or twice a week.

“It’s not a big deal since everyone does it,” she said.

Police officers cannot pull drivers over specifically to check if they are abiding by these restrictions.

Drivers must have committed another infraction, such as running a red light or speeding, for police to legally pull them over and charge them.

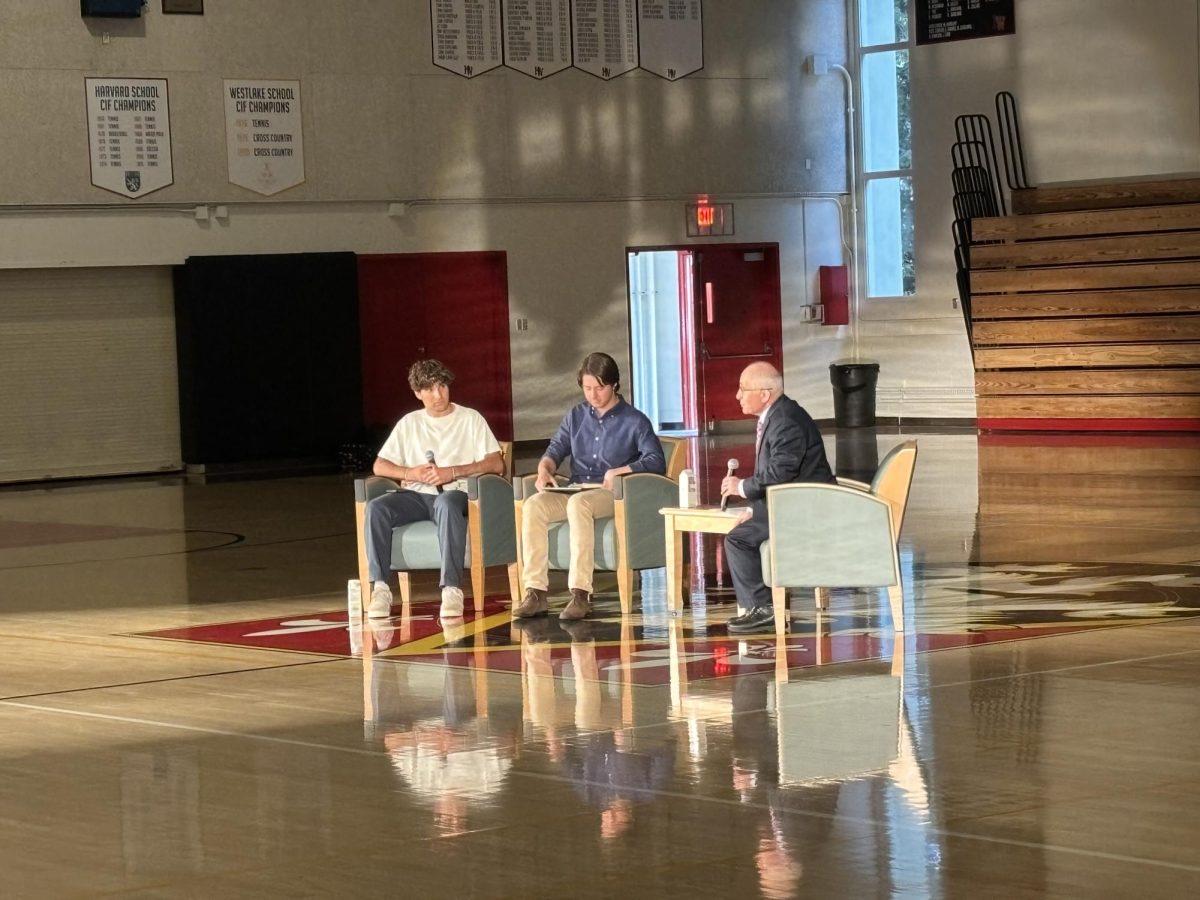

“As far as laws go, it’s still a relatively new law,” attorney John Dewell ’90 said. “Most police officers who are enforcing this law didn’t grow up under it, so they don’t necessarily check for it. But that’s changing as people become of age, and the younger police officers who grew up with it are familiar with it.”

Although the law mentions several exceptions, including medical emergencies and sometimes school, they are not often applicable to drivers in high school.

“Let me put it this way,” Dewell said. “The quickest down and dirty answer is that there is no exception for carpooling to and from school.”

For the first year after obtaining a provisional license, minors cannot regularly carpool, with the only possible exception being an underage student who is also attending the school.

This is a gray area because “your parents would have to write you a note stating what the reason is, that there’s no alternative means of transportation, and that this will go on during this given time period, one month, two months, three months,” Dewell said. “And it does take a pretty good reason for doing it.”

For Harvard-Westlake students with immediate siblings they could potentially carpool with, this “gray area” is mostly inapplicable because the bus service would qualify as an alternative means of transportation.

It takes a specific type of situation to qualify for this exception, said Dewell. Siblings that qualify would need to live in an area where school busses or adequate public busses could not reach them. If their parents were also unavailable to drive them and the sibling did not have a license or the family owned only one other car, the siblings would qualify as having no alternative means.

“You have to try everything else first,” Dewell said. “What they’re really driving is they don’t want you with kids your age, especially in school situations.”

The requirements for this exception correspond with this interpretation because a signed note from the school, not parents or guardians, is required to qualify for this exception.

“It can be a note by someone from the school, either a dean or someone above that level,” Dewell said. “Clearly, you’re not going to get that from the school, that’s why it doesn’t apply.”

Despite the law’s rigidity, 44.6% of the 35 students who answered this question in the Chronicle poll responded that they illegally drive passengers under 20 at least once a month, with 7.5% of the 35 breaking the law daily.

Sabrina* ’14 used to give rides to her friends; however, a recent speeding ticket caused her to think twice about letting anyone under the age of 20 into her car. Now that she has the ticket on her record, being pulled over with a minor in her car would be a second strike and could result in a suspension of her license.

“I used to drive other people, drive past curfew,” she said. “My parents completely allowed it, so I didn’t really care.”

Penalties for first time violations of the provisional license restrictions can include a fine of up to $35 and 8 – 16 hours of community service. Repurcussions increase with a second violation: fines are up to $50 and 18 – 24 hours of service can be assigned.

“The fact that your license during those first few years between 16 and 18 is provisional, pretty much the courts can do whatever they want,” Dewell said. “The courts can say, ‘You know what? We’re going to suspend the license and not let you drive for a year.’”

The fear of having her license suspended has stopped Sabrina from breaking any driving laws.

“The curfew my parents set for me used to be around 3 a.m. but since I got my ticket it’s been pushed to 11 p.m. to comply with the actual curfew [law],” she said. “I also basically never drive anyone, maybe once a month under special circumstances, but that’s it. It’s not worth getting my license taken away for.”

*Names have been changed.