Â

By Nika Madyoon

An explosion pushed her away, and everything turned pitch black. She heard nothing; Hiroshima was “a dead city.” Just a moment ago she was with her friend, standing in town admiring the beautiful sky.

Then she saw the nuclear bomb drop from the silver airplane up above.

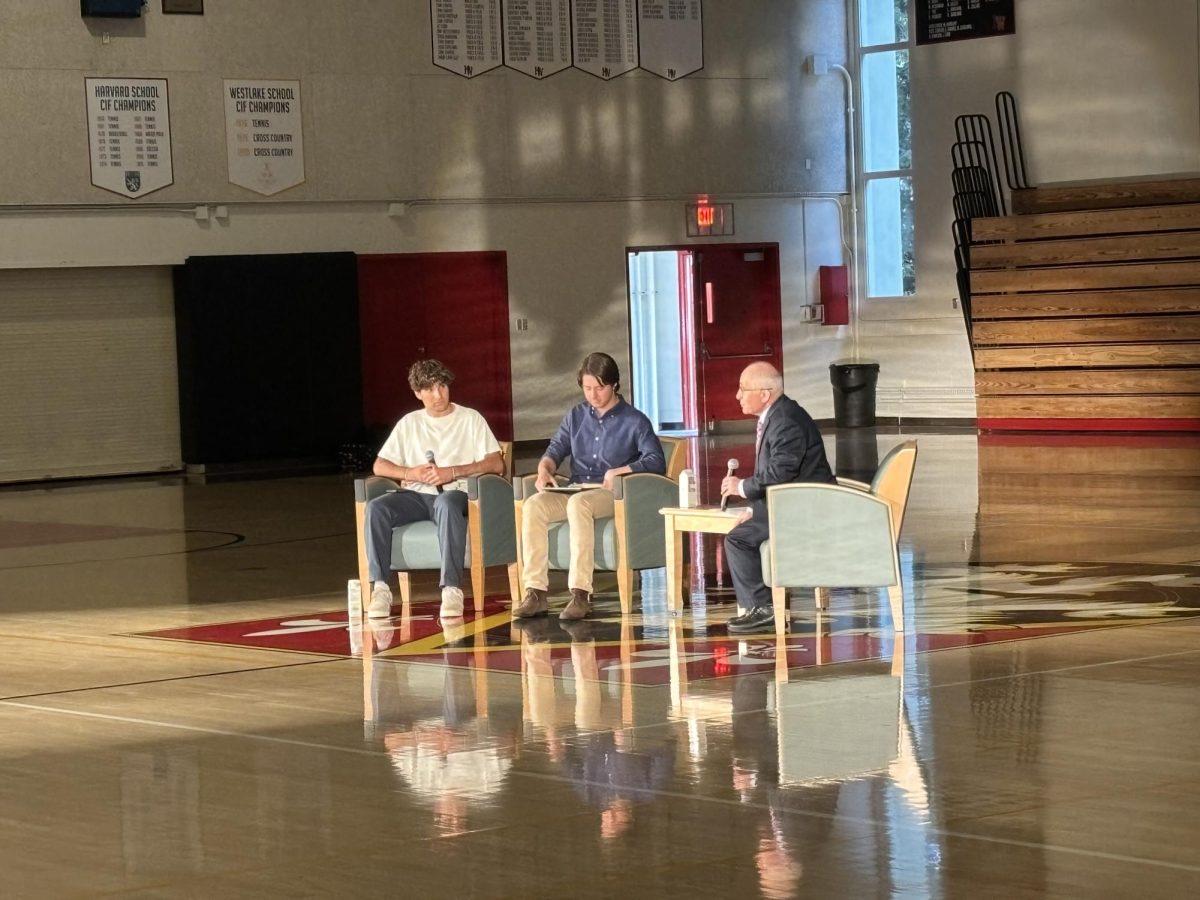

Shigeko Sasamori survived the bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and she shared her experience with students and faculty members in Feldman-Horn last week.

The meeting, though primarily set up for students in Japanese classes, was open to anyone interested.

Sasamori, who was 13 years old at the time of the bombing, was burned on her hands, face, and chest. Her legs, unlike many other victims, remained intact. She said it was a miracle that she survived. She recalled her laziness that saved her legs that day.

After work, she was accustomed to taking off her dirty pants and changing into a clean pair.

But that day, she simply added another layer of pants, without which sheâs not sure she would still be able to walk.

After the bombing, she was placed in a school auditorium with the wounded, where she stayed for five days without food, water, or care.

She heard the moans of fellow survivors, but she was unable to open her eyes, or even to distinguish between night and day. Asking for water and reciting her name and address were all that she could muster.

Her mother searched for her every day after the bombing, calling out her name.

“Here I am,” Sasamori said upon hearing her mother.

Her mother heard the quiet voice and found her daughter. Later on, her mother told her that she was unrecognizable. Sasamori said her mother described her face as black, swollen like a basketball, and covered in burns and ashes.

Her father proceeded to cut off all of her burnt hair. She warned the audience of curious students and faculty that the next detail would be gruesome: he cut the skin around her face and peeled off the blackness, only to reveal a yellow, puffy infection consuming her.

Soybean oil, she said, was the medicine of the day, replacing doctors and modern medication.

The city was “like a hell.” Maggots and flies ate up the bodies that littered the streets. The explosion led to a fire that engulfed the city. She described it as a “fire ocean.”Â

Sasamori told the story of her motherâs best friend, who told Sasamoriâs mother how lucky she was to have found her daughter. She was not as fortunate. Sasamori emotionally described the womanâs story.

She found her oldest child trapped beneath the remains of the city, still alive. After trying with all her might to save her child, she saw the fire approaching.

Her daughter told her to leave, to go take care of the two younger siblings she had at home. She was forced to leave her first child there to be consumed by flames. Stories like this, Sasamori explained, were not at all rare.

Despite the horrors she has faced, Sasamori remains extremely positive. She continued to remind the audience how happy she was to meet them, how they give her “wonderful energy.”

She stressed the importance of communication, telling of her experience in America and of how fond she is of the country and its people.

Sasamori was one of 25 Japanese girls adopted by Norman Cousins as part of his Hiroshima Project in 1955. The Hiroshima Maidens, as they were called, were taken to Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City for reconstructive plastic surgery.

The nurses that helped Sasamori during her recovery inspired her to want to become a nurse. She returned to Japan later in life and spoke with her father, who encouraged her to make a decision based on what she really wanted.

Describing herself as “so naïve,” Sasamori says she returned to the United States.

She explained that Japanese people and Americans may look different, but are really the same inside.

“We can think, we can talk, we can do,” she said.

Sasamori is against war.

“War is a horrible thing. Donât you think?” she asked the audience.

When her son was born, she took one look at him and said, “This baby is not going to war.” She didnât want him to kill, explaining that killing makes one a criminal. Most parents would not want that for their child, she reflected.

Sasamori reminded the audience how lucky they were, urging them not to sit on the “lucky seat” for too long, for they would someday fall off.

She told them that sitting and crying about what happened in the past does not help anything, encouraging them to worry about the future and what they can do to change it.

“You have a big future waiting,” she said.

And the key element to presenting future stories like her own, she explained towards the beginning of her story, was: “No more war.”

A loud round of applause filled the room once the period came to an end.

“Keep smiling,” she said.