A white line of powder cut across his reflection as he took out a small silver straw to take a hit off a mirror in his desk drawer. Moments after he finished, his students rushed into the office to surprise him with a teaching award.

Two grams of cocaine had become part of performing arts teacher Ted Walch’s daily routine when he taught two decades ago at a private school in Northern California.

“I had thought, ‘You’re going to be named the most outstanding teacher’ — that’s going to be great,’ ” Walch said. “But here I was feeling guilty and miserable and awful.”

Although Walch rarely used at school, the drug was always within his reach — in his car, his pocket and lined up, ready to go in his desk drawer — if he was desperate as he was on this particular day.

He considers the incident, nearly being caught by his own students, one of the darkest days of his addiction.

A colleague had first offered the “exotic, high-priced, out-of-the-mainstream” drug to the then 36-year-old teacher in 1978.

For Walch, the fast-acting stimulant became a powerful addition to an already-established schedule of drug and alcohol consumption.

“I loved to do a rhythm of martinis followed by cocaine, followed by shots of Nyquil to wash down Valium, followed by Percocet to wake up and repeat the cycle all over again.”

Alcohol was a part of the culture he grew up in and since his college years, Walch had considered himself a “maintenance alcoholic.” Every day, a drink was the “first thing picked up” and the “last thing put down.” Cocaine provided a “nice balance” to alcohol’s mellow buzz by making him feel “vibrant, jazzy and alive.”

When he tried cocaine, Walch knew that nearly every male in his family had struggled with addiction, especially alcoholism.

“I don’t recall or, perhaps, I don’t prefer to recall knowing the consequences [of cocaine] for someone who clearly as I do has an addictive personality,” he said.

White

Marvin* ’15 did not know the kids at the party who offered him cocaine and was not sober when he headed to the bedroom in the back of the house with the strangers to snort a few lines.

“White,” he said. “I remember it being very white just lying there on the dark wooden table.”

When the cocaine began absorbing into his blood, Marvin’s pupils dilated while his heart rate and blood pressure climbed. The stresses on his body put Marvin at risk for a heart attack and seizure. Though rare, his first use could have resulted in sudden death, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

It would take a few minutes for Marvin after snorting the cocaine to perceive the increased energy and euphoria that would last anywhere from 15 to 30 minutes.

“At first, I felt amazing and limitless,” Marvin said. “Words can’t describe how invigorated I felt. It was like an explosion of happiness and energy.”

The intense high from cocaine which Abigail* ’13 describes as “pretty enjoyable” experience led her to continue using it. She first tried it at the start of her senior year, when college students brought cocaine to her friend’s kickback.

“I won’t do it on a regular basis,” Abigail insists, calling herself a “dumb teenager.” “It’s all about experimenting.”

Upper school psychologist Sheila Siegel said teenagers ignore the potential repercussions of using cocaine.

“The initial motive is experimenting and part of adolescence is trying to individuate and doing things your parents don’t approve of,” Siegel said. “Unfortunately, with cocaine, it feels really good and you don’t realize the cost.”

More high schoolers have learned to steer clear of cocaine since the height of its popularity among teenagers in the 1990s. The number of 12th graders reporting past-year cocaine usage continued to decline from 5.2 percent in 2007 to 2.7 percent in 2012, according to the 2012 NIDA Monitoring the Future survey.

For Abigail, the best part of cocaine’s high was how she felt more “social and comfortable than ever before.”

Walch echoed her sentiment, describing how the drug made him feel like a more articulate version of himself. But in the end, he refutes the notion that cocaine is a social drug to be used at parties and makes users more talkative.

“You don’t sleep,” Walch said. “You think weirdly. It’s incredibly isolating. You have blackouts and fears that Lord knows where they come from.”

Marvin woke up terrified and paranoid the morning after he had tried cocaine.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, repeated cocaine use can cause irritability, panic attacks, paranoia and even “full blown psychosis.”

Although he recalls the high fondly, Marvin does not plan to continue using cocaine.

“Cocaine was awesome but I don’t think it’s worth it when you think of the big picture,” Marvin said.

Despite knowing these risks, Alex* ’14 does not think he’ll use enough cocaine to suffer the long term consequences and said he minimizes the dangers by only using the drug in “safe environments.”

If he were caught he could be sent to jail for up to a year. As a felon, he would lose his right to vote and the arrest would haunt job applications for the rest of his life.

Citing the existence of “functioning coke addicts,” Alex remains confident that he will not succumb to the negative effects of the drug.

“If the drug is significantly decreasing the happiness or value of my life, I can stop on my own,” Alex claims.

Walch warns of the decreasing high of the powerfully addictive narcotic as a user becomes tolerant to the drug.

“It is the most incredibly addictive drug because it’s never as good as the first time. But you keep hoping it might be.”

Towards the end of his addiction, the only high left for Walch was the “thought of scoring the cocaine.”

“The actual cocaine itself didn’t even have a high left,” Walch said.

Down and Out

Seven years of using cocaine left Walch $40,000 in debt. But he still needed to satisfy his $200 a day addiction.

“All you want is to either have the drug or know where you’re going to get it next,” Walch said. “It’s a diabolical instrument.”

In dire financial straits, Walch saw an “opportunity not to be missed” when a student came to confide in Walch his own problem with cocaine, not knowing that his teacher was also addicted.

“My cocaine problem was that I was in debt and needed cocaine,” Walch said. “His cocaine problem was that he was rich but he had a cocaine problem. So what did I do, I tried to use him to score cocaine.”

“You will do anything to get [cocaine] if you are hooked. You will go against everything that you truly fundamentally believe,” he added.

Shortly afterwards Walch regretted what he did and went to the student’s parents to tell them what happened.

“I have a problem,” Walch told them. “I’m going to deal with my problem and your son has a problem and I hope he deals with it.”

For the first three years of his sobriety, Walch went virtually every day to Cocaine or Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. Getting clean became the top priority in Walch’s life.

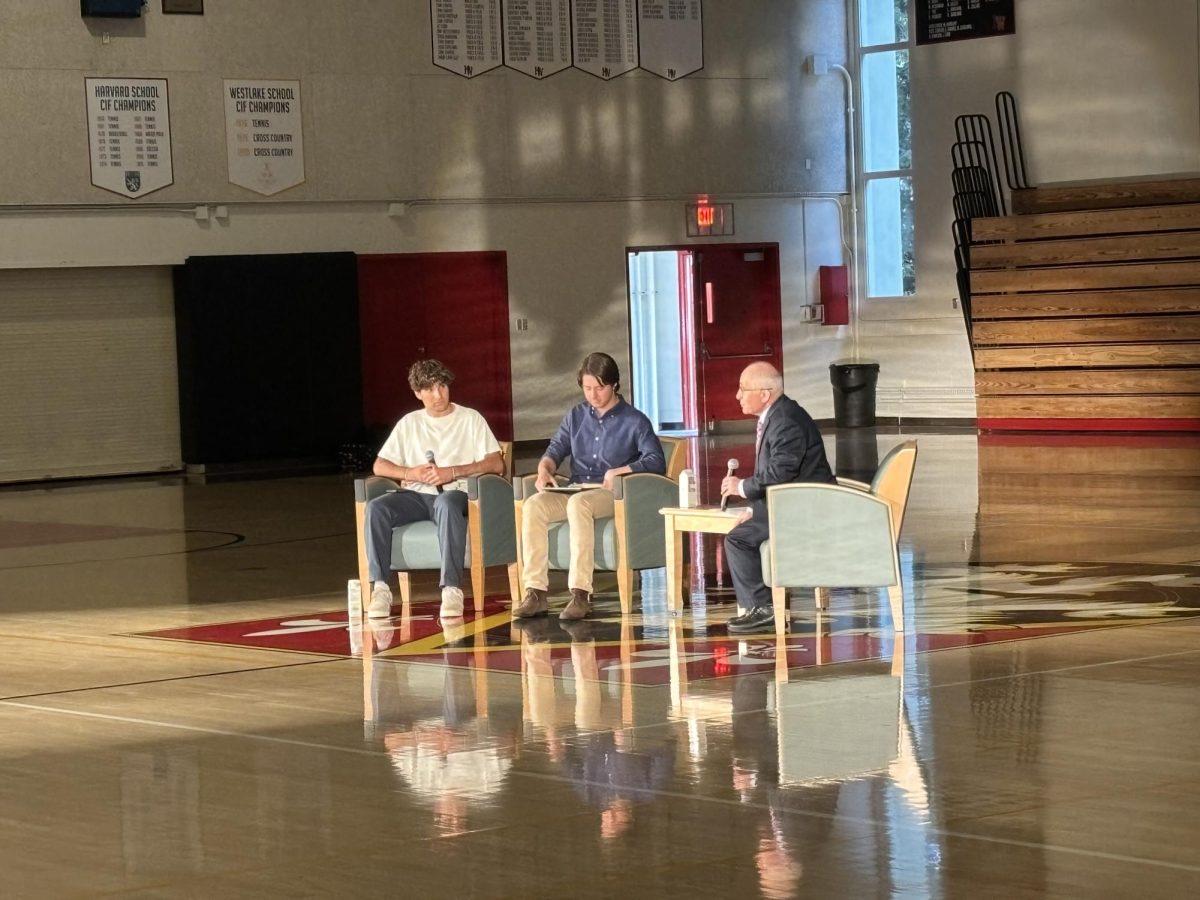

He credits old friend President Tom Hudnut, who was also headmaster of the school where Walch worked at the time, with supporting him as he tried to overcome his addiction. Walch admitted his cocaine problem to Hudnut who he had known for over a decade at the time.

“Deal with it and if you don’t deal with it you’re out of here,” Hudnut told him.

“Had I been caught [with cocaine] I’d have been fired in a nanosecond,” Walch said. “But I dealt with it. The friendship survived and was strengthened and enriched.”

Walch no longer attends meetings on a regular basis but does go when he feels the need to do so. Over the years, he has helped students deal with their drug problems, drawing upon his own experiences.

“[Walch] made me realize that being sober didn’t mean being a boring sod,” former student and Emergency Director at Human Rights Watch Peter Bouckaert said in a 2005 Rolling Stone profile.

28 Years

When he teaches “Paradise Lost” in Philosophy in Art and Science, Walch notes “something incredibly addictive” about Satan’s personality.

“[Satan] can’t stop doing the thing that harms him,” he said. “He knows it’s not going to lead to pleasure.”

“I knew intellectually that cocaine didn’t do anything for me except awful things but I hoped that just maybe I could get back to that first high.”

When Walch celebrated his 70th birthday last year, the student who he once tried to score cocaine from and his mother were both there.

“When I go to San Francisco, I stay at [the mother’s] house and [the student] is one of my closest friends,” Walch said. “So, that’s kind of a marvelous ending to an otherwise possibly sordid story.”

His 70th birthday marked another anniversary — 27 years of sobriety from alcohol. Two weeks prior to his last drink, Walch had stopped using cocaine.

“I’d still be drinking today if it were not for cocaine,” Walch said. “Cocaine brought me to my knees. Cocaine did me in.”

Additional reporting by Sydney Foreman

*Names have been changed.