By Faire Davidson

At the end of July, the total number of Manx speakers in the world rose from 54 to 55 and Harvard-Westlake became the leading source on the language in the United States. All because Nick Merrill â09 spent three weeks on the Isle of Man.

Merrill spent his summer on the small island between England and Ireland stretching a mere 32 miles long as part of the Junior Summer Fellowship grant he received last May.

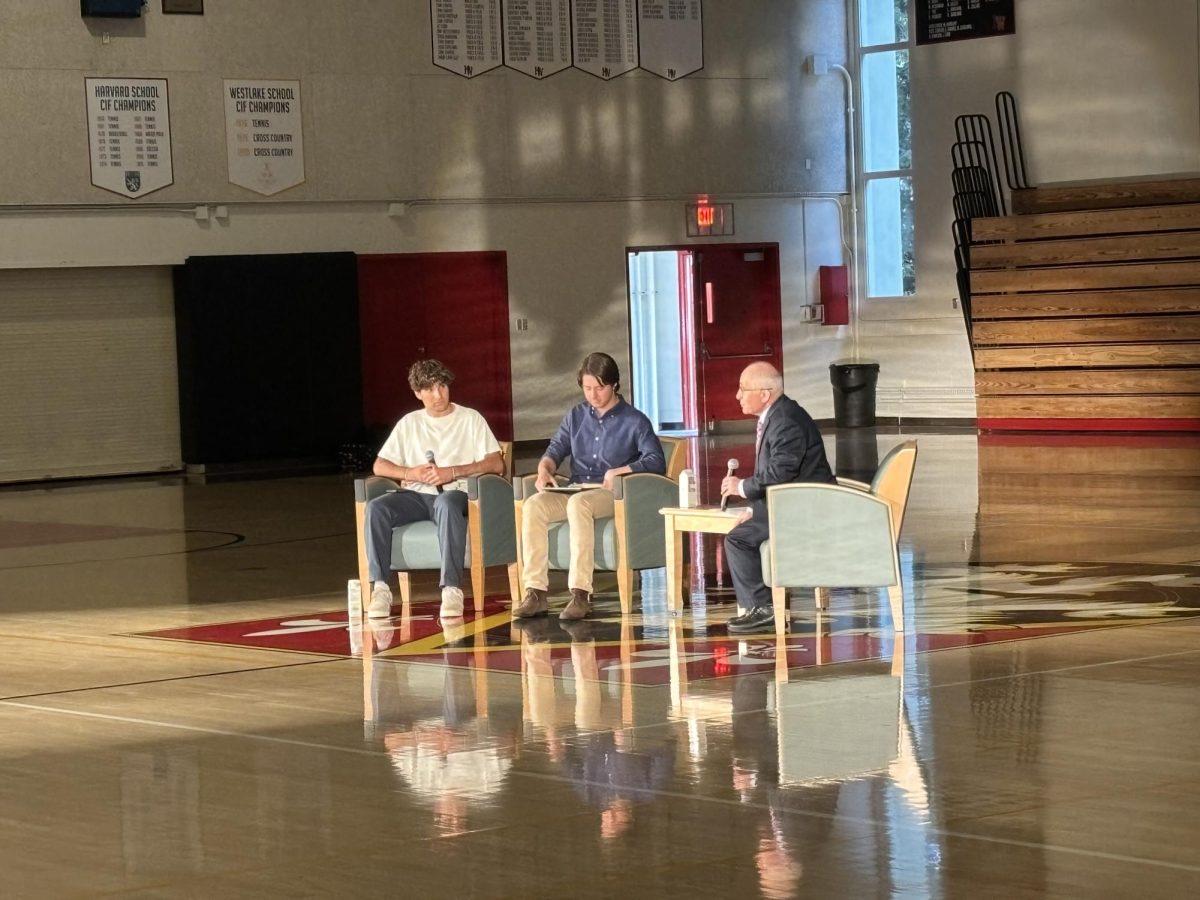

He proposed a project to learn the nearly-extinct language of Manx, the native language on the island. His proposal was chosen out of seven others created by students and sent to school president Thomas C. Hudnut.

“His proposal was unique, well-researched, thoroughly investigated and well presented,” Hudnut said. “It also dealt with a somewhat quirky, very unusual subject that might soon disappear, so I thought finding out about the Manx language before it died out completely would be a worthwhile project.”

In order to find a subject for the fellowship, Merrill began by researching endangered languages. The native language of the Isle of Man was noted as under “extreme risk” of becoming an extinct language. He described the language as a small piece of Englandâs medieval past and a living relic, something that deserved to be preserved.

“My purpose in going to the Island was to examine the cultural forces that push a language to the brink of extinction and to thoroughly document and record the language in case it ever dies out completely,” Merrill said.

For his Independent Study course, Merrill will detail his experience in a 40 to 50 page paper outlining the history of the Island, the language itself, Manxâs threat of extinction and its recent revival.

Manx began to die out in the 1950âs when many people began to deny they spoke the language because of pressure coming from the U.K. about English being a more proper language.

One local was curious about the dwindling number of Manx speakers and found an older native speaker to teach him the language.

In the 1980s, he began a class to teach Manx out of his home. It grew and in the 1990s the class became extremely popular and public interest in Manx began to spread.

“Adults who had never heard a word of Manx in their life greeted one another with typical Manx greetings,” Merrill explained.

Strangely, the island is a developed nation but began to lose pieces of its culture when the number of Manx speakers shrunk and nearly disappeared. Merrill saw the danger of complete homogenization with the United Kingdom as an immediate threat and Manx as a way for the Isle of Man to retain its individuality. Although the Isle of Man is not part of the United Kingdom, it is crown-dependant, meaning that Britain does have some influence in its government. This close relation with the British people could have contributed to the diminution of the language, something Merrill will explore when writing his independent study project.

For three weeks Merrill lived in a boarding school in the city of Castletown along with archaeology students from the University of Liverpool who were excavating Rushen Abbey nearby.

He shared a suite with four students from the university at King Williamâs College, which ressembles a small castle.

He spent time with these students exploring the area and getting a better sense of the islandâs culture. A few days after his arrival, the Duke of Lancasterâs regiment of Her Majestyâs Army arrived as well. Although they stayed across the campus, their early morning workouts on the cricket lawn became an alarm for the rest of the lodgers.

In order to learn the language, Merrill took the train daily to various towns and explored the area to find Manx speakers. With a tape recorder and a notepad, he interviewed native speaking children and locals.

Other days were spent tracking down Manx books and recordings to use to study and will be donated to the library when his research is done. Most text and recordings concerning the language are rare outside the island and until now, nonexistent in the United States.

Merrill also sat in on Manx classes being taught to young children. After the class, he interviewed the students to find out more about their reasons for taking the class as part of his research on why it is being revived.

He found them very enthusiastic to learn more about their culture, an interest that surprised Merrill. He also visited Bunscoil Gaelgagh or the Elementary School of Manx, which had taught 40 students who are now fluent speakers.

While much of his time was spent learning the language, he also focused on learning about the culture of the island. One local told him “the best part about the island is that you make it yourself. There iânt nothinâ to see. âTis what you find in it, the island is.” It is lessons like this that Merrill learned from the locals that he brought back with him to the United States.

Although Merrill technically went to the Isle of Man to learn a nearly extinct language, his experiences on this small island in the middle of the Irish Sea have amounted to more than expected, making the main goal of his trip, personal growth, exceed his expectations.

Merrill summarized his experience in few words: “Thereâs a Czech saying: âThe amount of tongues you know, the amount of times you have been human.â Iâd argue that this principal applies not only to language but to all of human culture.”