Just down the street from the Koreatown H Mart is St. James Episcopal School, where elementary school aged kids say goodbye to their parents, run around with their friends and share snacks before class starts that morning. Tiffany Armour ’25 just got off the bus where she was picked up from her house in Inglewood. While most kids are spending the last few minutes of their morning thinking about where they will sit in class or what they will be eating for lunch, Armour is reminding herself of the words she is not supposed to use in order to fit in with the rest of her non-Black classmates.

“I went to elementary school in Koreatown, so there were a lot of white people and a lot of Korean people, but I was one of the only Black kids,” Armour said. “By hearing kids at school talk I realized that I just gotta tap into a different part of myself when I was at school versus back at home. It’s second nature to me now, but it wasn’t always automatic.”

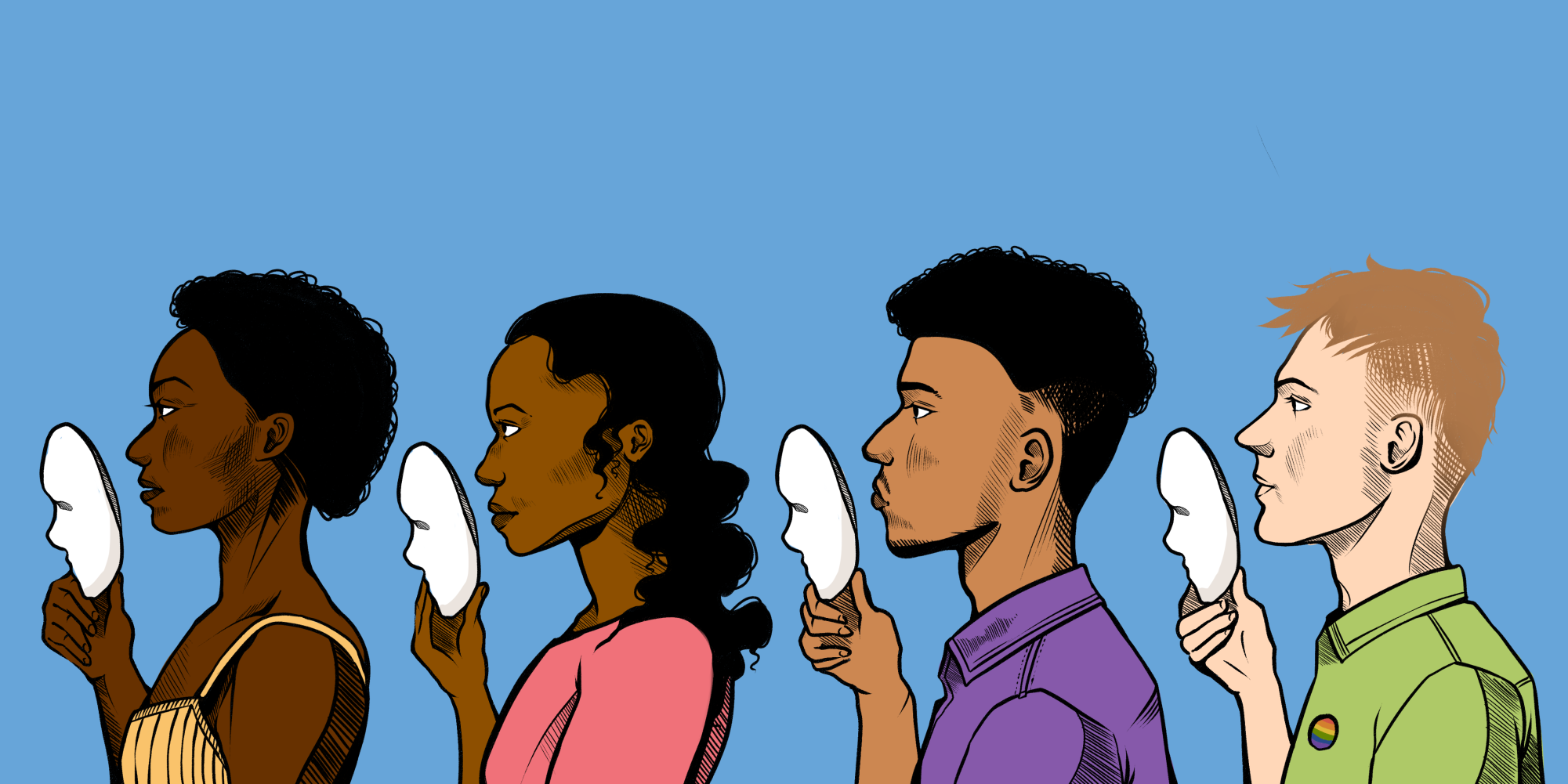

Code-switching is a common practice for members of minority groups where a person changes the type of language they use in order to better fit in with their environment. Black and Hispanic employees are most likely to code-switch in professional environments, with 35% of Black employees code-switching in the workplace, compared to 12% of their white counterparts, according to a 2023 survey by Fortune. Armour said that when she is in formal situations, she changes her dialect to seem more serious.

“If I’m in an interview or I’m talking to my teacher, I will fully get in that zone and think about every single word before I say it,” Armour said. “In those moments where I’m really conscious of it, I tell myself, ‘Okay, right now we have to turn off funny Tiffany and relatable Tiffany’ and I have to separate myself from the way I usually talk with my friends. A lot of the time it comes from not feeling like I belong in a certain space.”

Code-switching is not limited to language. According to the Harvard Business Review, people can code-switch through appearance, physical gestures and facial expressions. Armour said she code-switches to avoid being associated with common stereotypes of Black women.

“Another big part of the reason I code-switch is because I don’t want to be seen as the ghetto Black girl or the loud Black girl that talks too much and always wants to fight,” Armour said. “There’s a certain way that Black women are portrayed in the media and in pop culture that is very much associated with [African American Vernacular English]. Even though I know no one would call me an angry Black girl, I still feel pressure because I don’t want to fall into those stereotypes.”

African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is a dialect of English that is typically used in African American communities, particularly in urban areas. Because of racial biases, AAVE is sometimes seen as an improper form of English, according to Psychology Today. Head Prefect Bari LeBari ’24 said his family doesn’t approve of his use of AAVE.

“My family doesn’t actually like the way I talk because they’re from Africa, so they’re like ‘You’re trying to sound so ghetto,’” LeBari said. “Most of my family speaks with Nigerian accents, but since I grew up in America, I was surrounded by the African American dialect growing up and I adopted that from the people around me. People definitely find it amusing and entertaining, and I use it when I’m joking with my friends.”

LeBari gave a speech to the school community on the first day of school at Convocation. He said he decided not to code-switch during the speech to connect more with his fellow students.

“I didn’t code-switch when I gave my speech because I think the way that I talk is engaging and fun to hear,” LeBari said. “When I was writing the speech, [the school] told me to address it to the students and ignore all the parents and faculty. That definitely made me speak more authentically since I talk colloquially with my friends in a way that I wouldn’t speak with adults.”

Code-switching is a practice that is also employed in the LGBTQ community because of community-specific slang words or tone of voice. Jackson Hollis ’25, who identifies as gay, said he adopts a less feminine way of speaking when he’s around straight men.

“There’s definitely a negative connotation around the way gay guys talk and act,” Hollis said. “It’s something a lot of straight and bisexual guys are afraid to associate with out of a fear of seeming ‘f*ggy’ themselves. When I’m around other guys, I definitely put in a constant effort to present myself as less feminine. Code-switching isn’t necessary for me to get through my day like it is for some other people, but it definitely plays a role in how I interact with others, since I try to be liked by people who may not be completely accepting of my sexual orientation.”

The “gay best friend” is a common stereotype of gay men in popular culture that portrays LGBTQ males in a stereotypical way, according to Cosmopolitan. Hollis said he plays into the gay best friend trope in order to fit in with his female friends.

“As a gay guy, I feel pressure to present in a more feminine way in order to make friends with girls, so I often lean into the ‘Gay Best Friend’ stereotype,” Hollis said. “With girls, I speak in a more animated way and my tone of voice changes. I find myself saying stereotypically gay things like ‘Yas’ or ‘Mama’ but that’s not my authentic speech either, it more comes from a need to fit into a predominantly female crowd.”

In addition to the Black and LGBTQ communities, code-switching is a common practice for many Hispanic individuals as well. Spanglish, a hybrid language that combines words from both Spanish and English, is common in many Latino American households, according to Pew Research Center. Natalie Ascorra ’24 said she began speaking Spanglish because she speaks both Spanish and English at home.

“I’m first generation, which impacts the way I speak a lot because at home I speak Spanish,” Ascorra said. “What ends up happening at school is sometimes a mix of English and Spanish will come out. My friend group is mostly people of color, so sometimes I’ll let my Spanglish slip out around them and they’re fine with it, but I think there are some people who would judge me for it.”

At many colleges and universities, part of the application process is completing a live interview. Ascorra said she tried to refrain from using Spanglish during interviews to seem more professional.

“My parents never taught me to code-switch, so during the college process I googled how to make sure no slang or Spanglish slips out,” Ascorra said. “That was really helpful in helping me prepare, but in a few of my interviews there were times where I slipped. I’m grateful that my interviewers were chill about it and didn’t make it too awkward.”

Counselor Brittany Bronson said she plans to teach her own kids about code-switching for their own safety in the future.

“When I was growing up my parents taught me to code-switch by telling me to be mindful about certain things I said,” Bronson said. “Now, as a mother of two Black boys, my kids are going to eventually get to a point where people view them as scary and I’m going to have to teach them about code-switching in the professional world but also how to code-switch if they ever get pulled over by the police.”

Bronson said she often sees students speak differently with white faculty members than with herself.

“There are some kids I know who are able to speak comfortably with me, but then when I see them interacting with a white counselor or faculty member they completely conceal the way they actually talk,” Bronson said. “Seeing that happen as often as it does makes my heart hurt a little bit, but I’m also happy that they feel comfortable enough with me to not put up a facade. The best thing we can do is keep talking about it and having the important conversations to make our communities more inclusive.”`