It was summer when Wilder Short ’18 first visited Bowdoin College. He had already visited a handful of schools, but when he toured Bowdoin’s campus in Maine, it felt different. As his student-led tour wrapped up, he locked eyes with his mom. They didn’t need to say a word—they had read each other’s minds: this was the college he belonged at. Come December, he would be admitted early decision.

Bowdoin had every element of his dream school. It was a small liberal arts college. Its curriculum struck the right balance between structured academics and freedom to different explore subjects. Maine had four seasons. Having grown up in California, he wanted to finally experience weather.

Another perk? Bowdoin is one of few schools in the country that has banned Greek life. Never seeing himself in the fraternity scene, Short said he would not have joined a fraternity at any school. He welcomed the absence of Greek life, an institution he felt could divide the community and make some students feel left out at a small school.

Bowdoin banned Greek life in 1997, one of several schools to follow Williams College’s lead in disbanding the organizations in 1962. The main factor in Williams’ decision to end fraternities—it was an all-male college at the time—was discrimination. When John Chandler, president of the school, found out about the “system of blackballing and secret agreements between some fraternities and their national bodies to exclude blacks and Jews,” he decided to end the institutions for good, according to Newsweek. Along with Bowdoin, Amherst and Middlebury followed suit, citing hazing rituals, alcohol abuse and sexual assault as reasons the bans were implemented.

Half a century later, these problems persist. Reports have repeatedly reaffirmed the correlation between fraternity culture and college sexual assault (fraternity members commit rape 300 percent more than non-fraternity members, according to The Guardian). Headline after headline details the latest in a string of hazing-related deaths, most recently that of Timothy Piazza, a 19-year old Penn State University student who was given 18 drinks in less than 90 minutes during a pledging event and tumbled down stairs, losing his life in February 2017.

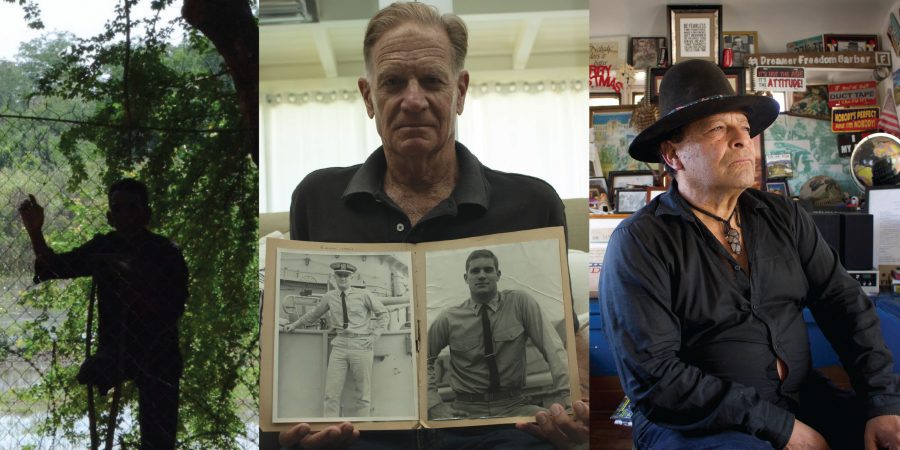

Former Sports Section Editor Jake Liker ’17 always knew the fraternity scene wasn’t for him. One of the main factors that deterred him from joining Greek life was the dangers of hazing rituals.

“If you join this organization, you may die,” Liker said of fraternities. “You will most likely be mistreated as a right of passage. There are not many reasons not to join a fraternity in the grand scheme of things. Rather, the reasons that do exist to not join a fraternity are very very impactful.”

Penn State president Eric Barron wrote an open letter following Piazza’s death, acknowledging that Greek life is responsible for excessive drinking and high rates of sexual assault and detailing reforms previously and newly implemented to bring those rates down at Penn State. But he also acknowledged that more extreme changes may need to be made: “the stories cited above cannot continue. If they do, I predict that we will see many empty houses and the end of Greek life at Penn State.”

What Barron is considering—the abolishment of Greek life on his campus—is something parents and administrators are advocating for nationwide. Many universities took action against Greek organizations this year in response to the hazing deaths that rocked the country in 2017. Hank Nuwer, a Franklin College professor who has researched hazing for over 40 years, said that this year’s retaliation against fraternities is the biggest he’s ever seen, according to Time. Several schools, including Ohio State and University of Michigan, temporarily halted Greek activities this school year because of hazing and alcohol violations. The University of Southern California announced new GPA and unit requirements to join Greek life, which means students are only eligible for Greek recruitment later in their college careers. Still, some colleges are considering taking bigger steps towards eradicating the problem. At Harvard College, a proposal sits on President Drew Faust’s desk, detailing a ban on Greek life that could be implemented as soon as Fall of 2018.

Liker questions the importance of Greek institutions in light of recent hazing incidents.

“Hazing is obviously different at different universities, but I’ve spoken to people who were basically tortured,” he said. “Like, I can’t, it’s bad. It just feels like fraternities and sororities, especially fraternities, their days are numbered in society.”

So, what does life at a college free of Greek life look like? Paul Leclerc ’18, who is attending Williams next fall, said that he appreciates the absence of Greek life because he feels it allows room for students to focus on building genuine connections with their peers.

“People are much less focused on ‘what fraternity am I going to join? What fraternity is good or bad?’” Leclerc said. “It’s more focused on just meeting people. I think it’s a bit more of a personal experience between kids.”

Leclerc, who was recruited by Williams’ swim team, expects the members of his team to take the place of his “fraternity brothers.” He said that one reason he chose to attend Williams over other schools he was considering was that he felt swimmers prioritized their fraternity brothers over their teammates at other schools where Greek life is an option.

“I wanted it to be like the swim team is really my second family,” he said. “In high school, you’re competing for yourself to get into college, but in college you’re competing for the school, for the team, for that family.”

Short said he is not concerned about meeting people and finding his niche in a new environment without the comfort of making immediate friends in a fraternity. Between being on the club soccer team, writing for Bowdoin’s satirical newspaper, staying involved in student government and joining film groups on campus, Short is confident he will find communities he belongs in on campus.

Both Williams and Bowdoin have made concerted efforts to ensure that students would have plenty of opportunities to find communities and make friends in lieu of fraternities and sororities. Both schools preserved original Greek houses on campus and repurposed them to serve as physical spaces for other student groups. Residential houses were implemented as replacements to Greek houses, which offer a similar sense of community but bring their own, new traditions. There is also an effort to ensure that groups on campus are not exclusive, so that students have many opportunities to meet one another.

While several schools’ decisions to ban Greek life have been met with success, others are hopeful that reforms and tighter regulation of fraternities and sororities will be enough to prevent future tragedies from occurring and change the culture of Greek life on their campuses.

Following Piazza’s death, Penn State launched an aggressive crack-down on its campus’ Greek organizations, announcing a set of 14 reforms that include the implementation of new positions in Student Affairs, random checks and monitoring of Greek houses to ensure compliance with school policies, stricter rules on serving alcohol and a revised pledging process, according to Penn State News.

Liker said although he would never join one himself, he does see the benefit of fraternities. While he wouldn’t be opposed to an outright ban, he supports attempts at reform as well.

“I think reforms can be made,” he said. “I’d like to be hopeful. My initial reaction is to be like ‘fraternities are bastions of toxic masculinity, sexual harassment and they should be shut down for the good of us all,’ but I do know people who have found fraternities to be very fulfilling parts of their college experiences, there is no denying that they do support charitable causes, and they try to instill certain values.”

Simone Woronoff ’16, a member of the Delta Delta Delta sorority, or TriDelta, at Northwestern University, recognizes that Greek life has many issues, but said her personal experience in a sorority has been overwhelmingly positive.

“I think [being in a sorority] has opened my eyes to a lot of problems Greek life has, and it’s made me want to change Greek life to make it more accessible to more people, just because I’ve had such a good experience,” Woronoff said.

Although she’s only been a member of TriDelta for less than two years, she has already been involved with developing crucial reforms for her sorority. She said her chapter of TriDelta is starting a scholarship to mitigate the economic barriers of joining Greek life, and that other fraternities and sororities on campus offer subsidies to students as well. Her sorority was also the first chapter on campus to implement a Chair of Diversity and Inclusion. Her sorority sisters and she are constantly thinking about ways to be more inclusive and ensuring students on campus know that Greek life is an option for them, she said.

Woronoff initially went Greek for the opportunity to connect with older students, something she felt she missed during high school. What she got out of it, she said, was a group of best friends. She also said being in a sorority makes her feel safer on campus.

“I definitely think, at least personally for me, as a woman and in this time period, it is incredibly nice to have 100 women watching out for me when I go out,” Woronoff said. “Say I didn’t come home—there’s always someone watching out for me. Not only is it friendship, it’s also sort of safety, and I definitely feel like I have a huge support system here.”

Certainly not every Greek institution is the same. Sororities may have some work to do with regard to inclusivity, but the most disturbing problems emanate from fraternities. If more schools began to ban fraternities, would sororities come down with them? Would students like Woronoff be barred from an experience that has been wholly healthy and positive for them? However, banning Greek life has historically yielded excellent results. According to Newsweek, students at Middlebury felt that once Greek life was gone for good, their lives improved. Women felt more comfortable on campus. Students felt more included, and they appreciated a new sense of equality. Outright bans on Greek life have worked—and worked well—for some schools, but reforms may be the solution at others, especially at those where Greek life is considered to be less intense.

One thing is certain. University administrators from colleges nationwide are beginning to come to the conclusion that the culture of Greek institutions, particularly fraternities, cannot go on the way they have been. The president of Penn State is leading a conference in April to discuss how to better control Greek life on campus with administrators of other schools nationwide, according to The New York Times.

“There are no easy solutions, and we do not claim to have all the answers,” Barron said in a USA Today column. “We will adjust and learn, and explore new ideas and best practices as we forge ahead.”