Harsh red swastikas covered the walls of an unassuming Columbia professor’s office Nov. 28. Scrawled in spray-paint, the word “Yid” was plastered above her computer screen. NYPD is investigating the incident as a hate crime.

Sophie Levy ’18, a Jewish freshman at Barnard College of Columbia University, looked at the image of anti-Semitism on her campus in disbelief as her friend showed her a breaking news article in a student publication.

“Now, my alarm bells are going off,” Levy said. “People say things here and there, but before this, I’ve never felt uncomfortable per se. The incident with the graffiti was the first time I was like, ‘Oh crap, this is scary.’ This happened on my campus.”

As a senior in high school, Levy traveled with March of the Living to Poland to learn more about the Holocaust. Experiences like that helped her realize that such forms of anti-Semitism are not new to 2018 but rather have always existed, she said. Yet, she said this was the first time such vehement hate affected Levy so closely.

“I feel like you just have this broader cultural memory as a Jew, and when something like that happens it hits a nerve,” Levy said. “After seeing the results of the height of anti-Semitism with my own eyes, seeing that on my campus 70 years after the Holocaust, using the same emblems and slurs that were used back then, was very disheartening, and it’s scary, really, for lack of a better word.”

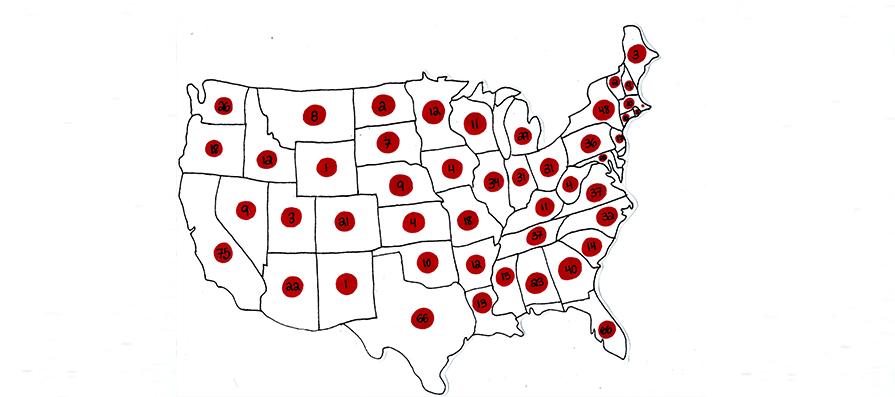

Last year, an FBI report concluded that there were 7,175 hate crimes that took place in America, a 17% rise from 2016. This continues the trend of a steady increase in hate crimes over the past three years.

The rise of hate crimes in the country is affecting a wide variety of minority groups. The FBI report, released in November, found that hate crimes targeting Jewish Americans increased by 37 percent and African Americans by 16 percent.

Since the FBI only takes into account hate crimes that were reported to the police in its statistics, some say its estimates are low. For example, the Anti Defamation League estimated that anti-Semitic hate crimes have risen by 57 percent, as opposed to the FBI’s 37 percent.

“It doesn’t surprise me,” Sophia Nuñez ’20 said. “With the current political climate, there is a lot of fear mongering and a ton of really strong language being used on both sides. It’s definitely used to create a narrative and to stir emotions within people, and they are not necessarily good emotions. They can be very violent and hateful, which is why there is a rise in hate crime. And when that language is normalized it makes sense that people would act on it.”

In correlation with nationwide trends, California also saw an up-tick in hate crimes last year. A report for the Attorney General’s office announced in July a 17.4 percent increase in hate crimes in the state. Specifically, hate crimes against Hispanic people in California have increased by 50 percent in the last year, according to NBC. In the state, there are 954 hate groups, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Out of 337 students polled, 32 percent said they feel this up-tick in hateful sentiments has affected them.

Shana Brindze ’19, who is both Jewish and LGBT, said they have been weary to attend temple since the Pittsburgh attacks and nervous to attend some LGBT events since the Pulse Nightclub shooting.

“Those events were really tragic and really scary, not just for our community, but for people everywhere,” Brindze said.

Similarly, Cassius Bythewood ’19 said that, as an African American, seeing the impacts of hate crimes on the news hits close to home.

“[When I’m] out and about sometimes I worry because, [in] my personal opinion, this new presidency has kind of made people who were undercover racists start to come out,” Bythewood said.

Although they don’t always feel safe off campus, Bythewood and Brindze both said they feel protected when they are at school.

Nuñez said she feels that the culture of hate in the nation at large normalizes insensitive and racially charged sentiments, that, at times, make their way onto campus.

“If you just look at our school in the past couple of years, while we are a pretty progressive campus, we definitely work very hard to make sure that this is an inclusive place, but we also have stuff like what happened on the Twitch stream last year, where someone was screaming the f-slur and the n-word a bunch of times,” Nuñez said. “Someone [at Harvard-Westlake] obviously has those sentiments and was trying to rile up others.”

When she was in history class, Nuñez remembered feeling upset but not surprised when a classmate of hers said that “all Mexicans are rapists.”

In addition, Levy said she remembered encountering what she referred to as “casual forms of anti-Semitism” while she was in high school — comments that never made her feel like she was in danger but made her feel uncomfortable.

“Usually, I’ve encountered more verbal stereotyping,” Levy said.

As a leader of the Black Leadership Awareness and Culture Club, Bythewood has facilitated conversations about both stereotyping and hate crimes with his peers. The club is comprised of students across the political spectrum who all have different ideas about why the incidents occur and how they should be combated, but the one thing everyone in the club can agree upon, Bythewood said, is that all hate crimes are unacceptable.

Having a space to process the events in BLACC is important to Bythewood, but he said those same conversations take a different tone when they include the broader school community.

“We all feel like we need to have a guard up even when talking to other students at Harvard-Westlake about it because I feel like a lot of times when we have conversations with other non-club members, it can get a little heated because of our strong opinions on how we feel as black people being affected by this, feeling like it could be me or one of by family members or friends affected by this next,” Bythewood said. “I’ve come to understand that not everyone can sympathize directly with me because they’re not going through what I am going through.”

Although they may be uncomfortable, Bythewood said it is important to include the whole community in the conversations to ensure that people of diverse backgrounds at Harvard-Westlake can feel that school is a safe space, as he does, in spite of the hate that is prominent in the country.

“If we face these problems head on, it will become more comfortable to talk about these issues,” Bythewood said.

As it is a priority for the school to create an environment where students feel comfortable despite nationwide trends, it is working towards educating teachers in how to have the types of conversations that Bythewood values inside and outside of the classroom, as well as training students to use culturally responsive language, President Rick Commons said. Commons credits that work to the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion office.

“We need to get a better understanding of how to communicate strong ideas in ways that are appropriate and never include hateful speech,” Commons said. “Specifically the creation a year and a half ago of the DEI office has allowed for really good conversation around how we can be a place where there is robust debate about things that are deeply emotional in many cases without crossing the line into saying things that are irresponsible in the way they affect somebody’s identity. There’s a lot of work being done.”

Head of Upper School Laura Ross said that there are two important factors to fostering such an environment: teaching history fairly and promoting an understanding for the value of community.

“I think part of it is making sure that that’s part of our curriculum: how the choices you make affect those around you,” Ross said. “I think in our more polarized country, people are just in echo chambers of whatever they believe and that allows you to ‘other’ people. This can go so far as to rekindle actual hatred.”

In the wake of this up-tick in hate crimes, Levy, Nuñez and Brindze all said that it is important for communities to come together in support of those who feel unsafe.

“If you hear something or see something, you have a moral obligation to criticize that and stand up against it,” Levy said.