Pencils down, time’s up

Students discuss their learning differences and extended time arrangements following quarantine and the return to school.

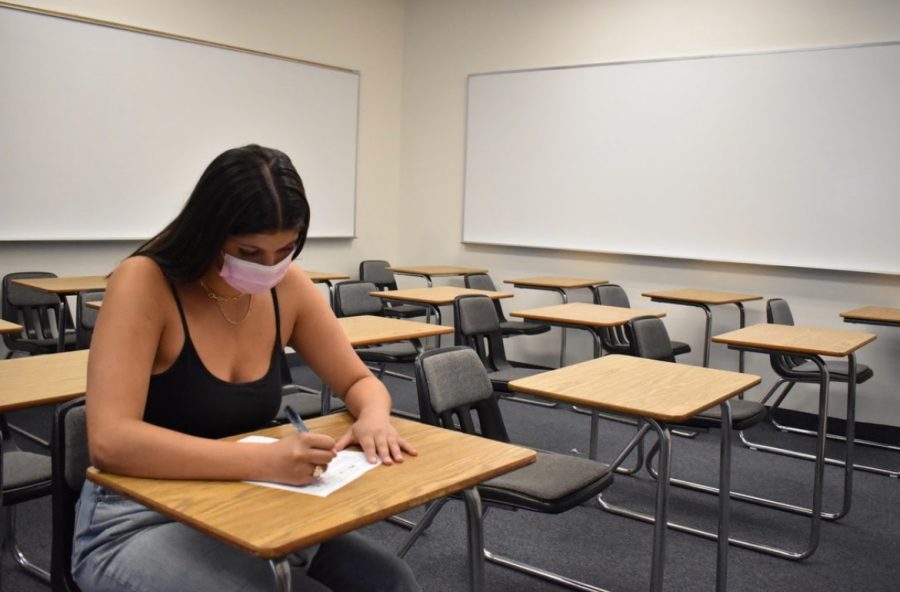

Shanti Hinkin ’22 takes her test in an empty classroom.

October 20, 2021

Cole Hall ’24 circled the final multiple choice problem on his spring biology exam and released a deep sigh of relief before handing it to his teacher. Hall said he realized he had never before experienced a comparable sense of calm or focus after taking a test. Originally diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in eighth grade, Hall said the virtual 2020-2021 school year proved an especially difficult hurdle to overcome.

Hall said he struggled to study for and take exams prior to quarantine but developed a new sense of focus and serenity during online learning . He said he has applied new study skills to in-person school this year and has noticed improvement in his ability to concentrate.

“[On my first test back in person], instead of needing the extra time like I normally did, I actually finished early,” Hall said. “The rest of the time I spent looking over my answers. For taking tests, it used to be about going fast, [but] quarantine has allowed me to quiet my mind and just focus on the work. Coming back to school, I am really just focused on what is being asked of me.”

While Hall said his time learning over Zoom ultimately allowed him to develop efficient learning strategies, Learning Center Director and Learning Resource Specialist Grace Brown said other students with testing accommodations reported adverse impacts from online learning. Brown said she has observed a decline in the general conditions of students previously diagnosed with anxiety or ADHD as a consequence of the new test-taking environment.

“I saw a lot of students who already had accommodations in place, and quarantine exacerbated their symptoms,” Brown said. “So either because they’re staring at the screen so much or just sort of the emotional impact of all that, it slowed their processing down. [Some] students who normally were fine with [150% of normal test time] needed more breaks. We saw an increase in the severity of symptoms [for students that require accommodations].”

Zen-mara Duruisseau ’22, who said she requires accommodations, said she has struggled with adapting to the classroom testing environment after a year of taking assessments from home.

“Coming back has been hard because I haven’t really been in school or [taken] actual tests since maybe 10th grade, two years ago,” Duruisseau said. ” I think to slowly get back into that normal testing environment, I’m [going to] have to start taking tests in a separate room, so I won’t feel [as] pressured by the fact that my peers are also there.”

While Duruisseau said she tends to have trouble concentrating primarily in overstimulated classroom environments, Rowan Jen ’23, who uses extra time on tests, said his ability to concentrate directly correlates with the amount of time he spends on social media. Jen said throughout the COVID-19 pandemic , he spent significantly more time on social media, which he said lowered his attention span and consequently increased his need for extended time on exams.

“I think [quarantine]definitely had an effect on [my] focusing skills,” Jen said. “I’m spending much more time on social media, which is inherently shorter form content. I think that I wasn’t focusing for long periods of time, [instead I was] just sort of scrolling away. In that regard, [COVID-19 has] Jen said his peers also struggle to maintain focus in school or on tests because of excessive internet usage during quarantine .

”A result of our generation is just constantly being stimulated and never really having enough time,” Jen said. “We’re always watching things on our phones, so in that way, I would say a broader population as a whole is losing their ability to focus.”

Assistant Director of Learning Center Ramon Visaiz said the school received an increase in applications for accommodations throughout and after quarantine. He said learning challenges became more apparent during this time.

“We have a greater number of students who now require accommodations and support, but that’s not the way to look at it,” Visaiz said. “The way to look at is we’ve identified that these students need this specific support. Whether it be reading or organizational skills implemented, that’s a good thing to identify because now those students aren’t [struggling with] the anxiety or the frustration of [whatever] they were [being] challenged [by].”

Visaiz said the school’s learning specialists noted a frequent overlap between students with learning disabilities and students struggling with mental health, made more apparent by the conditions of quarantine.

“We noticed there were a lot of mental health concerns surrounding students or families not knowing they needed accommodations,” Visaiz said. “A lot of what we recommended was [learning accommodations] testing throughout that process. This year, we have a lot of students who [were given additional] support, but that support came as a result of those challenges.”

President Rick Commons said online school affected each student differently and that he believes quarantine became a time for the community to reflect on learning abilities and obstacles.

“I think all of us in the school have discovered an entirely new way of going to school,” Commons said. “For the month [before] the school year, we discovered things about our learning styles, learning preferences and learning differences. There [are] students [who] depend especially upon the in-person, collaborative aspect of learning that was absent for so many months […] We’re all evolving from the pandemic and hopefully discovering how to be better learners.”