Condoms mingled with the usual pencil shavings and old worksheets in the trash can, and a single bruised banana sat, out of place, in the recycling bin. The classroom was still. An hour or so before this, scores of students, some blushing beet red and others blowing the latex into balloon animals, stretched condoms around bananas here. This activity was part of the school’s sophomore sex education (sex ed) program. Under a desk at the back of the classroom, a bright green sticky note lay on the floor. The other sticky notes hung crookedly on the white board. Scrawled on each sticky note was a question about sex ed written by a student. Maya Karsh ’25 said her sex ed class, which met in her English classroom, had a lighthearted atmosphere during this activity.

“I remember doing some activities with brightly colored Post-Its and having to place them on a board depending on what we knew and what we didn’t know,” Karsh said. “The questions we had were really awkward, and then they would be read to the class, and it was funny trying to [figure out] who wrote what questions.”

Five days of activities, such as the one Karsh described, make up the school’s sophomore sex ed curriculum. The curriculum includes topics on sexual health, sexuality and gender, sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy prevention and social media.

Sex ed is “high quality teaching and learning about a broad variety of topics related to sex and sexuality. It explores values and beliefs about those topics and helps people gain the skills that are needed to navigate relationships with self, partners and community, and manage one’s own sexual health,” according to Planned Parenthood.

In California, sex ed is required for public school students in grades 7-12 at least once in middle school and once in high school. This requirement exists because of the California Healthy Youth Act, which was enacted in early 2016. Having sex ed as a part of the curriculum is very popular among parents, with a Planned Parenthood poll reporting that at least 90% of parents support this type of teaching.

Nationally, 38 states and the District of Columbia require sex ed, according to Guttmacher Institute. Each state maintains the right to regulate sex ed, which contributes to the ongoing battle over how children are educated and what they are taught. For example, educators in Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas and South Carolina are permitted to present homosexuality in a negative light, while elevating and promoting heterosexuality, according to a U.S. News and World Report article.

According to “School Health Profiles 2020: Characteristics of Health Programs Among Secondary Schools” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of students who have received sex ed of any kind, abstinence-only or comprehensive, is declining overall.

“Despite strong evidence and support of sexual health education, national estimates show fewer students have received such education in recent years,” the report said. “Nationally representative data from 2011-2019 indicates that youth aged 15-19 experienced significant decreases in receipt of key sex education topics (i.e., delaying sex, birth control methods, HIV/AIDS prevention and STDs); including marked disparities by race/ethnicity and gender in receipt of sex education.”

The Class of 2024 did not receive sex ed during high school because during the pandemic, Planned Parenthood did not have enough educators to teach the program the school previously used, according to Upper School Counselor Tina McGraw ’01. Last year, the school introduced a new sex ed curriculum from the nonprofit “More Than Sex-Ed.” For the Class of 2024, the sophomore seminar program was not focused on sex ed. Ellery Shapiro ’24, who did not attend the middle school, said during the sophomore seminar program, she did not learn about sex.

“In Life Lab, we did this presentation,” Shapiro said. “We each had a different thing like homelessness, vaping and lack of food. It was about problems in the world. I think some people don’t know how to participate in safe sex because they didn’t learn at a time where it was important.”

Health education at the school is currently provided in eighth and 10th grade. However, the curricula are different because students are in different stages of development. Sophomore Prefect Caroline Cosgrove ’26 said she learned about sex in the eighth grade human development class, but that was not the main focus of the class.

“As an eighth grader, we learned how to practice safe sex and the most efficient ways to prevent any sort of unwanted pregnancy,” Cosgrove said. “However, we definitely focused on emotions and how they affect different hormones and the way we act much more than sex, like our desire and impulses for substances.”

For the Class of 2025, the school brought back sophomore sex ed, which they had not taught since before the pandemic. McGraw said the school uses this curriculum to present well-rounded sex ed to students.

“We teach the sophomores four lessons from the LGBTQ+ inclusive program created by ‘More Than Sex-Ed,’” McGraw said. “Those lessons include information about various topics from STI prevention to social media and sexuality. They are also closely paired with presentations from SafeBAE, which discuss consent.”

The lessons also include information about various forms of contraception. Since the Adolescent Family Life Act passed in 1981, many schools have taught abstinence-only sex ed, a curriculum that stresses that premarital sex should be avoided, according to Advocates for Youth. Abstinence-only sex ed is not effective in preventing teenage pregnancies because teenagers are not deterred from having sex, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Rather, they do so without proper knowledge of how to have safe sex. The school does not teach abstinence-only sex education. Janice*, a student who has received sex ed in the past, said that she got birth control before she had sex for the first time.

“I am a very anxious person,” Janice said. “I didn’t want to be like, ‘Oh my god, oh my god, I’m going to get pregnant.’”

While Janice has taken sex ed before, she said she feels like sex ed surrounding birth control is generally insufficient.

“I wish there was more education about different birth control methods,” Janice said. “As females, we don’t really get that many options and all birth control kind of sucks. There’s so many downsides to it and it’s so stigmatized that you don’t really talk about it with that many people. I just think that if we had more education about it, people would be more aware of the different choices. I wish I was more aware of the different options out there for birth control before I chose what I did.”

Upper School Counselor Michelle Bracken said because many sophomores are in different developmental stages, sometimes the sex ed they are given feels like it does not resonate with their lives.

“I think [sex ed is] something we need to be talking about in developmentally appropriate ways in each grade level,” Bracken said. “So I think the way it’s taken, lots of people are rolling their eyes probably thinking, ‘Oh, my gosh, I already know about all this stuff.’ But to me, I still feel like we need to be talking about those things, and we need to be delivering the information as well as being able to have open conversations. That’s not an easy thing to do.”

On the student side, 106 out of 182 students who responded to a Chronicle poll said they felt the school’s sex ed curriculum is adequate. Jacob Massey ’25 said he thought the 10th grade sex ed course was necessary and informative.

“I thought it was the most useful and prudent way to teach us about our changing bodies and the changing world that we inhabit, for without comprehensive sex ed we will only cause more unwanted pregnancies, STDs and more,” Massey said. “I’m not afraid to say it. STDs are bad.”

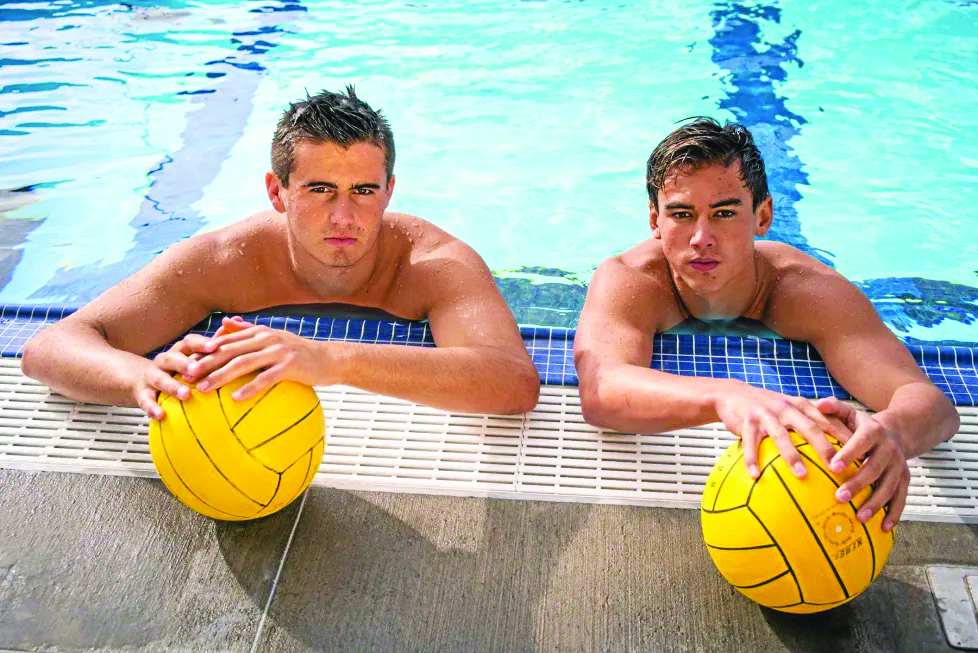

During this course, students partnered up to put a condom on a banana. Junior Prefect Victor Suh ’25 said that, while he found the activity to be strange, he understood the overall goal.

“I was like, ‘Okay, this is happening now,’” Suh said. “[It was an ] interesting exercise. I understand what the purpose is obviously. It’s just familiarity, and [familiarity is] never a bad thing. I do think it’s a little weird. If I try to step outside of myself and look as an objective third party observer, I feel like there’s nothing bad to giving everybody the same opportunity to get a feel for that kind of thing.”

Reflecting on his perceptions of the grade’s general reaction to the sex ed course, Suh said he thinks most people likely took something away regardless of whether or not they realize it.

“Even though I doubt that most people will consciously say that they walked away from it learning anything, the fact that they did it has to mean something, even [if] it’s not consciously educational,” Suh said. “[There is] always some merit to [making] sure that everybody gets equal opportunity and experience with that kind of stuff.”

Karsh said she thinks the 10th grade course was less meaningful than the eighth grade one, although the 10th grade class resonated more because she was older.

“[The 10th grade class] didn’t make a lasting impact on me, but I feel like it was more of a review session,” Karsh said. “In eighth grade, we had human development, which really drilled it in there, even though that was online. I feel like that was more extensive information. In 10th grade it feels like way more relevant information. It’s a lot more timely. I feel like they should maybe do shorter courses every year instead of just giving it to you all at once.”

Upper School Counselor Brittany Bronson said that sex ed needs to teach students how to act responsibly during sex and reflect different identities.

“It’s imperative that students have the knowledge on what safe sex is and the measures they can take to protect themselves and their partners,” Bronson said. “It is also important that sex education curriculum is inclusive of all gender identities, expressions and orientations. When I received sex education in high school, we only learned about [cisgender] male and female bodies and heterosexual relationships. It is a beautiful thing to witness the growth of sex education and how all encompassing it has become.”

Massey said he thinks that if sex ed is something that students need to receive, then school is where they should receive it.

“I think that our schools are our primary source of learning, so if it is felt by our society that this is an important subject that needs to be taught, then school is the best place to learn about that subject,” Massey said. “Schools should have a hands-on approach to sex education.”