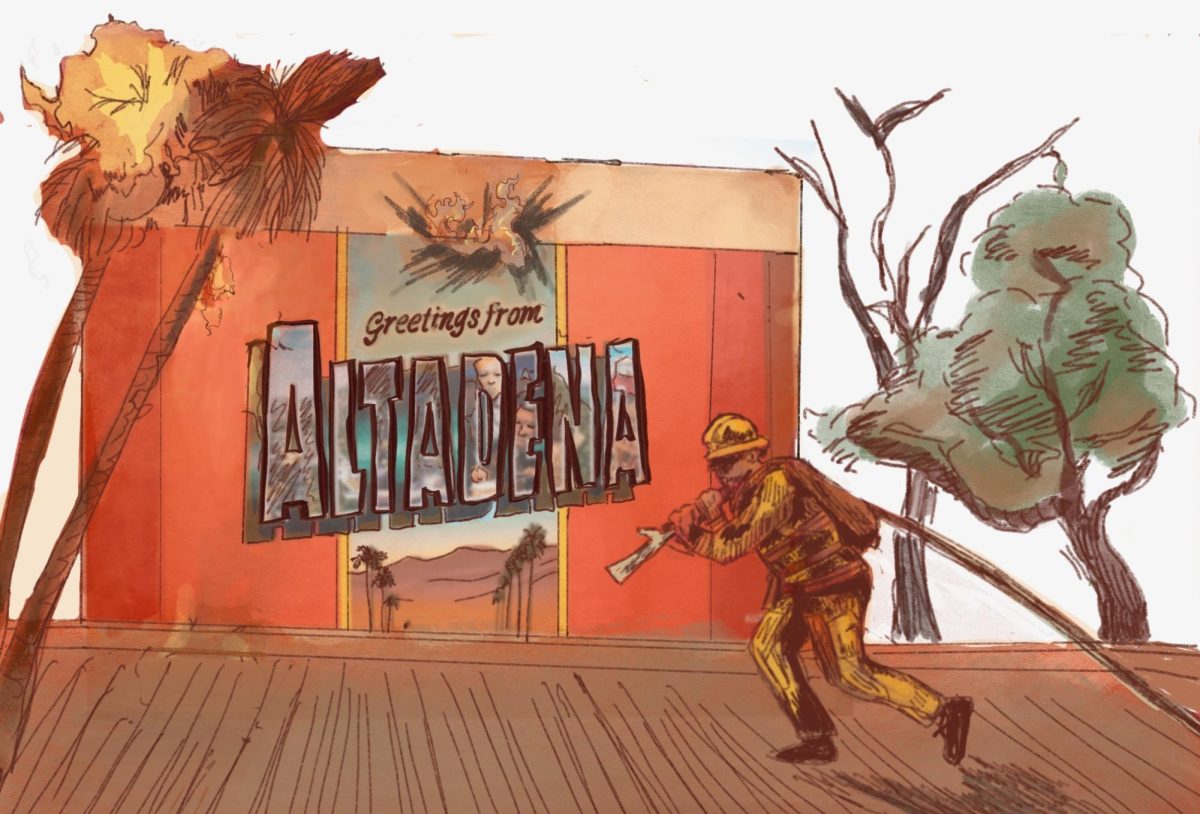

Keisari Penman ’27 steps out of the car, smoke stinging her eyes. After evacuating the night before, she is on her street to assess the damage done to her home. Her garage is ablaze, and a pile of smoldering embers sits where her house once was. Her home, located in Altadena, was lost to the Eaton fire, which burned over 14,000 acres of Altadena and Pasadena, according to Cal Fire. Penman said seeing her home burn was emotionally devastating.

“We went back to our house to see it completely gone,” Penman said. “The only thing there was a chimney. Our garage was standing [when we left], but when we went back a couple hours later, it was on fire. After seeing our garage [burn], I couldn’t imagine watching my entire house on fire. I didn’t know if I could handle it.”

The Eaton Fire, which started on Jan. 7, damaged or destroyed over 10,000 structures and killed 17 people, according to Cal Fire. Although the fire is now fully contained, it has left many Altadena and Pasadena residents displaced.

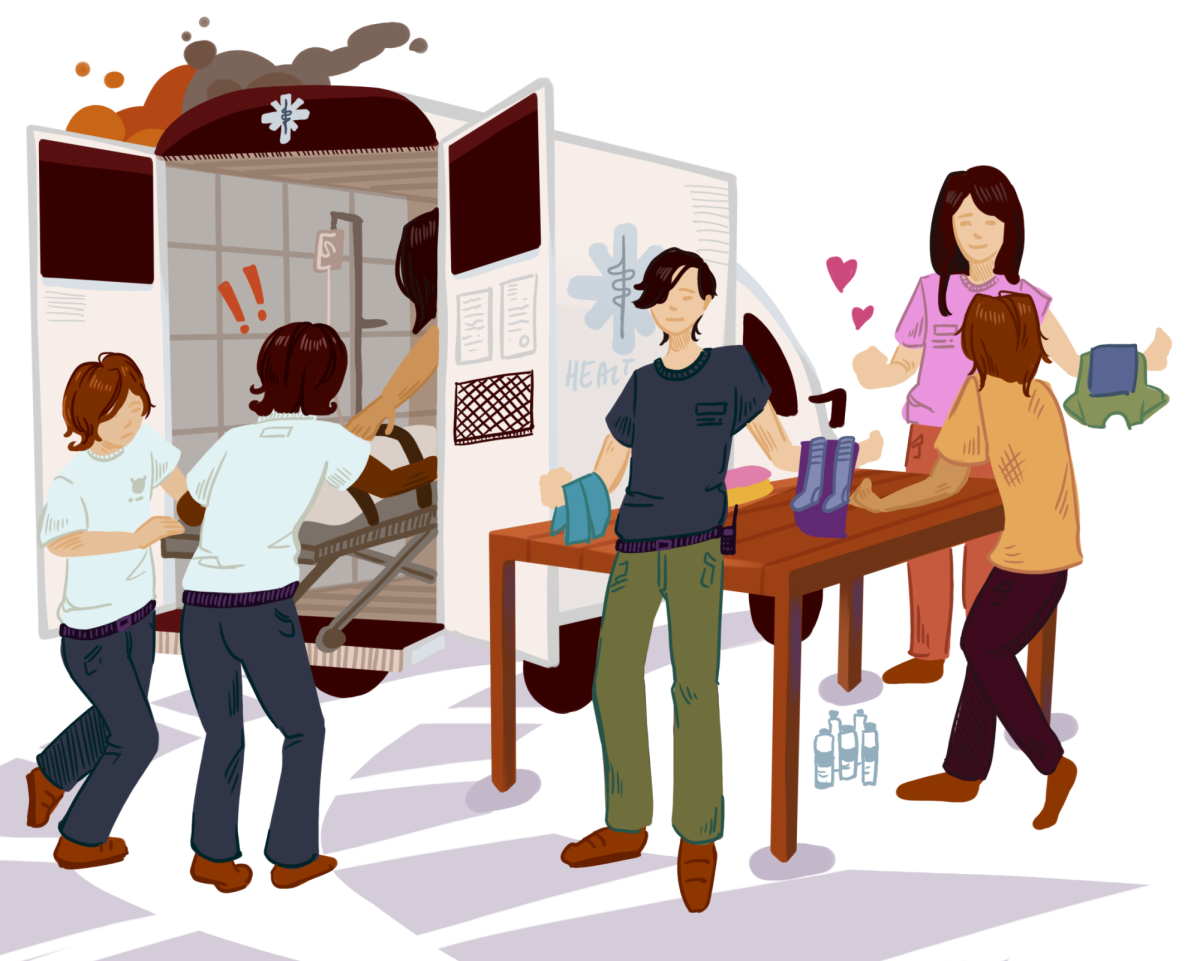

Penman said after the fire, the Altadena community was very supportive and rallied together.

“The best part [of living in Altadena] was being around so many people who provided a sense of comfort and support,” Penman said. “You had your home, but the whole community felt like a home. There’s a sense of comfort in Altadena that you’ll probably get in no other place.”

Penman said she felt immense sadness and grief for the place that held her most important memories.

“Everything happened in that house,” Penman said. “In a home, you’re supposed to feel comfort and warmth. Watching that all go feels unbelievable and beyond crazy.”

Altadena is a community with a distinct history that has been shaped by its geography, residents and demographic shifts. Altadena’s development can be traced back to the mid-19th century when Benjamin Eaton, a civil engineer and the fire’s namesake, helped establish irrigation systems that made it possible to settle in the dry San Gabriel Valley. In the late 19th century, Altadena emerged as a residential community, according to Altadena Heritage.

By the early 20th century, Altadena was an attractive destination for wealthy residents. Opulent estates were built along Mariposa Street, and restrictive racial covenants limited property ownership to white residents. A significant shift occurred after World War II, when the 1948 U.S. Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer made racial covenants unenforceable, according to Oyez. Altadena became one of the first neighborhoods in Los Angeles with areas that allowed Black home ownership, making it desirable for middle-class Black families. Despite some resistance from white homeowners, Black families, mostly professionals seeking better housing opportunities, began moving to Altadena in the 1950s and 1960s.

Altadena was 95% White and only 4% Black in 1960. Things changed with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. More Black families moved in, and by 1970, Black residents made up 30% of the population, according to the U.S. Census. However, by the turn of the 21st century, due to gentrification and the rising prices of Altadena’s real estate market, there was an influx of wealthier homebuyers and residents of other demographics. By 2020, Black residents decreased to 18% of Altadena’s population.

Gian Ngo-Willis ’26 is an Altadena resident. His house is one of three that remains standing on his street. He said that although Altadena is home to people of many different backgrounds, he has recently noticed heightened gentrification within the community.

“Altadena is a very diverse place,” Ngo-Willis said. “There is some slight gentrification coming in that I’ve seen. There have been a lot of white-owned businesses popping up and taking out some of the older Black businesses. It’s a pretty small number at this point, but you can definitely see a change. There have also been a lot of white people buying homes and renovating them.”

Adrian Drouin ’26, who’s house survived the Eaton fire, said the aftermath of the fires has the potential to accelerate the displacement of residents of Altadena.

“As of late, there have been more white people and Asian people moving in, but it was mostly Black and Brown for a while,” Drouin said. “Post-fire, I think this could get [worse]. People could just rebuild the area and try to sell the homes for crazy amounts. People are already getting offered [money] for their land, and it’s probably going to get flipped and resold. It has the potential to kick a lot of people out.”

Ngo-Willis said the media coverage of the Eaton fire has a different tone than that of the Palisades fire due to the socioeconomic differences between the two communities.

“The Palisades obviously has more resources to rebuild,” Ngo-Willis said. “Altadena has a lot less resources to rebuild, so I feel like that has been a focus [of the media coverage], which is good. When it comes to Altadena and Pasadena, [the media portrays the fires] as a horrible thing that’s happened on a much more personal level.”

Penman said the Altadena community is showing resilience as it begins to restore the neighborhood to its original state.

“You realize how close of a community you have when you see the response in times of crisis like this,” Penman said. “All my neighbors are dedicated to moving back in, rebuilding and coming together to help one another even throughout all this. What’s so great is that a lot of people want to rebuild and want to get back to what Altadena was. It will never be the same, but it can be close.”

Ngo-Willis said the community’s action-oriented response to the fires has been inspiring.

“The community reaction has been astounding,” Ngo-Willis said. “It’s been beautiful to see all of Altadena coming together since we are a very tight-knit community. There are people offering their services, their time, their hands and their bodies to help put out the fires and make sure they stay out so we can continue to live in our neighborhood and be safe.”