All students attending Harvard-Westlake have gone through its application process, most with help from parents or guardians.

Youna Choi’s ’17 experience was different from others’. Her mother speaks Korean and has a limited understanding of English, something that led to problems when she applied to high school. Choi’s older sister, Eojin Choi ’14, helped her instead and translated for their mother.

“It was the most difficult with Eojin,” said mother Hyejeong Joo (Eojin Choi ’14, Hyunseok Choi ’16 and Youna Choi ’17) in an interview in Korean. “We had to request help from someone who was more well-versed in English. With Hyunseok and Youna, it was easier because their older sister, who had the first-hand experience of going through the process, was able to help them and help me help them.”

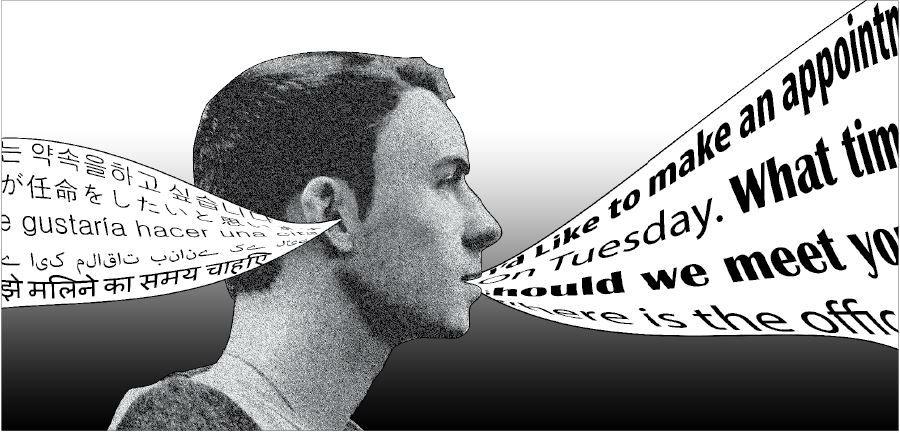

Bilingual students whose parents do not speak English say they have to interpret for them in such everyday situations as making doctor and dentist appointments in addition to more occasional situations like an application process.

Jazmin Piche ’15, whose parents speak Spanish, said that when she was in sixth grade, her mother’s employer suggested she apply to Harvard-Westlake.

“We didn’t realize I could even apply until my mom’s boss said private schools offered financial aid,” Piche said. “My mom’s boss helped us out a lot because we knew no one who had applied before.”

Jim* ’15, who said that his father speaks broken English and his mother speaks no English at all, had a different experience from most of his peers applying to Harvard-Westlake and, more recently, to college.

“I think [applying to Harvard-Westlake] made me more responsible and independent because I had to take care of most of the paperwork and translating,” Jim said. “Especially now that I applied to college, most of the weight of the process lay on me because of the language barrier. I learned to be resourceful in finding information and dealing with the hassle alone.”

Upper School Dean Beth Slattery said Harvard-Westlake interviewers accommodate their interviewees’ English abilities. When applying, prospective families have access to translators to help ease language barriers. After acceptance, however, these benefits stop being offered.

“I know I have a very fast speaking pace, so I’m very conscious of providing opportunity for a translator to speak,” Slattery said. “In addition, the admissions office takes into account an interviewee’s level of communicative ability with their interviewer. If they are unable to communicate as effectively in English as they are in the language they are most comfortable with, the admissions officers understand that they are not getting a full picture of what the person is like. It would be unfair to pit a complete picture against one that is only partially finished.”

Some students think the school should do more to help families that don’t speak English after they are admitted. Once enrolled, Piche found herself in situations that were never a problem for her peers. During events the school hosted, her parents found it difficult to participate, and more often than not, these language barriers affected her parents’ relationships with the school.

“I think there should be people offering to translate at every parent function,” Piche said. “That way, parents can go around with the parent translators and talk with people, and if they don’t understand, they ask their parent translator. For example, if there’s a dinner party, there should be an option on the invite for ‘parent translator available for this and this language’ and list the names of the parents and which languages they can translate.”

Slattery believes that parents decline to attend parent functions because of language barriers, and that students with non-fluent parents also tend not to tell their parents about school events.

“I usually send e-mails to the parents to solicit them to come in, rather than leaving it all on the student to handle,” Slattery said. “I think what is very common among students who speak another language at home is a sense of independence. Rather than discussing something at length with their parents, because it’s time consuming or sometimes too difficult to translate, they tell their parent that it has nothing to do with them, or that it’s something they don’t need to worry about. This isn’t ideal in a school-to-family relationship, so I try to reach out directly to the parents.”

Sahar Tirmizi ’16 has spoken Hindi and Urdu since she was young, and switches between the two depending on the situation. Her parents both speak English, but she speaks native languages at home because her parents want her to remain connected to the culture.

When with friends, Choi, Piche and Tirmizi speak in English in order to avoid any awkwardness that may arise from language differences. And when they bring their friends to their homes, where they might be heard speaking in other languages, they have varying experiences.

“My friends, they know with time what my ‘ethnicity’ is, for a lack of a better word, so whenever I’m talking with my parents in Hindi, they won’t be surprised, though they may be a little uncomfortable maybe because they don’t know what I’m saying,” Tirmizi said.

Choi sometimes finds that bringing non-Korean friends over to her house is difficult.

“It can be awkward, and it can make it hard for me to get permission for others to come over,” Choi said. “My mom wants to avoid having to talk to people, especially parents, because she can’t understand them well.”

More often than not, constant exposure to English has decreased students’ opportunities to practice their native languages.

“My brother and I naturally now speak English [with our parents], but they encourage us to speak in Hindi to keep the language alive,” Tirmizi said. “We go back to India every summer. Whenever we do that, we have to be able to talk with our family in Hindi, so we have to keep practicing.”

Jane* ’15 lives with her mother in the United States, while her father lives in Japan. Her mother spoke very limited English when the two first immigrated. Jane recalls having had to write formal e-mails to her teachers on behalf of her mother when she was in fourth grade, and making doctors’ appointments by the time she was in sixth grade.

“I used to think, ‘Why is [my mom] making me grow up so fast?’ whenever I saw the parents of my friends writing their own e-mails and making their own phone calls,” Jane said. “I didn’t realize until later that the independence early on would really help me. Now my friends are scared of interviews and sending formal e-mails, but it’s so easy for me because I’ve being speaking to adults since I was young.”

Despite the challenges speaking more than one language may bring, students say that the benefit often outweighs the losses.

“Being raised bilingual is probably the single asset I’m most grateful to my parents for having given me,” Jim said. “Hispanics are very proud of their language because it lies at the center of their culture. I really don’t think I could have been as connected to my heritage had I not spoken Spanish. There’s also a lot of criticism and shame attached to not knowing how to speak Spanish. I’m not going to lie, but the best part is being able to talk crap with my mom around other people without them knowing. I don’t want to scare anyone, but if you hear people speak in a different language around you, you probably do not want to know what they are saying.”

Jim also believes that his knowledge of the Spanish language will help him in his future career pursuits.

“Over the summer I shadowed a few doctors at a neighborhood hospital,” Jim said. “And what stood out to me was how many patients only knew Spanish. As more and more Hispanics move to the U.S., I see bilingualism as becoming more of a necessity in any career that Americans pursue. I know it’ll help me communicate with this rising demographic.”

*Names have been changed.