Growing tired, the Dungeons and Dragons players flung spiked chains and a flaming sword at the golden throne. The vampire sitting on it wouldn’t budge, and he was a stronger villain than they had ever faced before.

“I told you I was taking the training wheels off,” Dungeon Master Henry Zumbrunnen ’16 jeered at fellow Dungeons and Dragons Club members Henry Muhlheim ’16, Hannah Dains ’16, Charlie Noxon ’17 and Cameron Wood ’15.

As our characters struggled to overthrow a powerful lord in the land of Goluvno, Zumbrunnen’s version of Russia, we sat at desks pushed together in Rugby 204, sheltered from that day’s rain. The blackboard at the front of the room still had notes on it from Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice.”

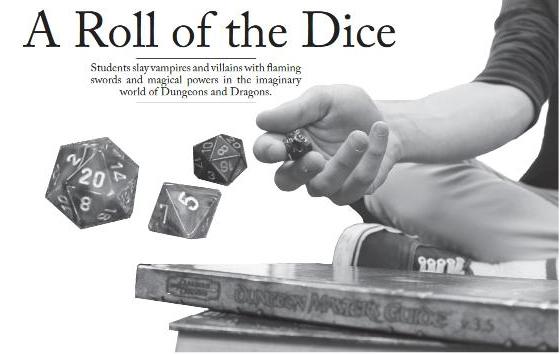

The fighters held onto record sheets to keep track of each of their characters’ skills and abilities, and Zumbrunnen, in the teacher’s chair, kept a spiral notebook and a manual in front of him. The members took turns making calls (for example, “I stab the vampire with my knife”) and rolling dice to see whether their characters would succeed in their actions. On a 20-sided die, someone who rolled a 20 would have a “critical success,” which meant anything he had planned on doing would go extremely well. A one, meanwhile, was a “critical failure,” which meant the opposite.

I’d expected to see more than a few dice and some pieces of paper in a game with such an impressive name as “Dungeons and Dragons,” but I learned quickly that the impressive stuff was impressive because it all lived in players’ imaginations, where there were no limits but the landing of the dice and basic plot continuity, which was the Dungeon Master’s job to maintain.

At least until Zumbrunnen started play rehearsals and couldn’t run sessions anymore, members of the Dungeons and Dragons Club met every week this year to take on fictional roles and embark on fantastical quests that he would narrate. Each member kept the same character all year, but each meeting consisted of a new quest. I attended one of these meetings, mostly curious because I had seen members dress up as their characters before.

When I walked in that Tuesday afternoon, the most substantive thing I would have been able to tell someone about the game was that it had something to do with dungeons. And dragons.

I played that day as Barrack the Struggler, a barbarian who carried a dwarven urgrosh — an axe combined with a spear — but stayed back from combat because of my inexperience. Originally, club member Malcolm Neill ’15 had played Barrack, but he hadn’t been coming to meetings lately. My character wasn’t very good anyway, Zumbrunnen informed me early on in game play, so even if I had tried fighting, I don’t think it would have helped much.

Zumbrunnen started the meeting by recapping the last session, in which Noxon’s and Dains’s characters had managed to burn down an inn. Today’s quest was to kill the blood-drinking lord of a giant castle in the neighborhood.

Muhlheim, who played a bard (bards, like barbarians, are a class of characters in Dungeons and Dragons), opted to try and raise an army of nearby villagers to help us kill the vampire. So he asked a village leader what he knew about our villain.

“Many people have disappeared from the village,” Zumbrunnen responded, now in a Russian accent because he was playing the leader serf. When Muhlheim asked whether he’d join us, Zumbrunnen stroked his chin. Muhlheim had rolled too low on the 20-sided die for his attempt at diplomacy to work.

“We have a lot of potatoes here,” Zumbrunnen said. “And wheat. And corn. But the one thing that grows faster than corn is regret.”

Muhlheim took that as a no.

We gave up on recruiting support and walked on to the castle, where our characters managed to get in by posing as a rapper and his entourage come to entertain its lord. Muhlheim’s character played the rapper because after all, he was a bard, and bards were professional poets in medieval times. Once Muhlheim had attempted to rap over a series of instrumental tracks played from his computer (“We’re storming the castle, ain’t no hassle, we’re little rascals”), Zumbrunnen’s narration took our characters to the back right turret of the castle, up two flights of stairs and two doors down the first hallway to a guestroom.

Dains rolled then to search the imaginary room for secret passageways and found a hidden staircase, at the bottom of which a vast arena made of glassy black stone awaited the characters. This was where they would face the vampire. (My character would stay in the room meanwhile, “keeping watch,” because I was scared to fight.)

Muhlheim, Dains, Noxon and Wood quickly put together a plan, shouting to each other all the while. Muhlheim’s bard would rap and distract the villain, and then Wood’s character would use his powers to build a wooden ramp up from the ground to the vampire’s throne while Muhlheim made 20 copies of himself using his mirror-image powers. Dains would disguise herself as one of those copies. Noxon got a call from his mother in the middle of this conversation, so his character had to sit out for the beginning of the attack.

When it came time for Muhlheim’s character to split himself, Muhlheim rolled high enough only to make one clone. Each swinging two chains that he carried as rapper gear, the bard and his copy zig-zagged up Wood’s ramp and struck the villain.

Muhlheim shook the dice, raising his hands above his head. “Oh God, please,” he said. But he rolled low, and Zumbrunnen decided that the chains would only glance off the villain’s shoulders.

After further attempts by the team to damage the villain using a laser beam, a dagger, a garter snake and a wild boar, Muhlheim made an admission.

“This guy’s a high-level boss,” he said.

Dana Anderson ’17 walked in, pausing the fierce combat. There had been few silences in the room through the last two hours of game play, and I’d forgotten that it was raining outside. Zumbrunnen stared at some guidelines with his nose two inches from the teacher’s desk. There was still a vampire to be slain, so Anderson joined in, piking the villain in the stomach. Muhlheim, who thought it was “all about style at this point,” called her move too plain. She should have cut off the vampire’s head.

The vampire died eventually, and the entire castle collapsed, for all along it had been a projection maintained sheerly by the villain’s willpower, Zumbrunnen told us. My character, Barrack, fell out of the room he’d been waiting in and landed in the snow next to the rest of the team.

Muhlheim gave a brief eulogy for the vampire: “So we killed a stranger, and we don’t know who he is or what he does,” and then it was time for everyone to level up. Using a black graphing calculator to add everything up, Zumbrunnen granted our characters 1,500 points each to signify the experience they had gained that day.

As the meeting ended, Anderson told me it had been relatively uneventful in the D&D world. Last year, Daniel Palumbo ’14 had played a sentient doughnut and rolled around everywhere he went.

“In this club you’ll have the best stories,” Anderson said. “But they’ll all be fake.”