At Virginia Tech, graffiti was written on the walls of a bathroom that read “I will be here 11/11/2015 to kill all muslims [sic].” At American University, threatening posters were hung with one that read “#StopTheJihadOnCampus” below images of knives, targets and blood.

Incidents such as the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting and the November 2015 Paris attacks, attributed to Islamic terrorist organizations, have sparked fear and outrage amongst many American citizens.

Students at various universities across the country are rallying against instances of racism and bigotry on their campuses, leading to multiple protests and demonstrations at prominent universities. However, less widely known than the “white girls only” remark at a Yale fraternity party or the resignation of University of Missouri president Timothy M. Wolfe is the rise in Islamophobic sentiment that has manifested itself increasingly over the past year.

At schools, this tension can be manifested in innocuous forms such as jokes or quips directed toward Muslims, or even in threats of violence and brutality against them.

Muslim student Ali Iken ’17 has noticed the exacerbation of discrimination against people of his religion.

“After any terrorist attack, I noticed that people started making more jokes that generalized all Muslims to be terrorists,” Iken said. “I really didn’t find them funny. I feel like now I hide my opinions more, especially with all of this discrimination from people like Trump. But ultimately, everyone is entitled to their opinions.”

Iken believes that Harvard-Westlake students experience less of the Islamophobic sentiment that may occur at large universities. While this is partly because Muslims constitute only a small fraction of the student body, it is also because students at Harvard-Westlake are exposed to the many different cultures of Los Angeles and are relatively educated on many aspects of the religion, Iken said.

Yet even in a city as diverse as Los Angeles, Muslim students have experienced some level of discrimination or hate.

“When I was in the third grade playing in the playground, a boy I knew came up to me and said he needed to poop,” Iken said. “I told him to go to the bathroom, but he said that since I was Muslim and Muslims kill people, I was as good as poop. So then he tried to poop on me.”

Insecurities that Muslims face are too often validated. A Muslim boy, age 14, was arrested in Dallas for his homemade clock, which the police mistook for a bomb. The incident led to a storm of criticism of the police for its apparent discrimination against Muslims.

Sahar Tirmizi ’16, who identifies as Muslim, considers her faith a large part of her life, and she practices Islam regularly through prayer and celebration of religious ceremonies. The violence and intolerance associated with Islam prevalent in various forms of media made her self-conscious to tell people that she is Muslim, she said. Tirmizi herself has been the subject of many Islamophobic comments.

“One of my teachers was saying that Islam is actually really similar to Christianity and Judaism for a number of reasons,” Tirmizi said. “One of the students made an audible comment along the lines of ‘don’t muddy the waters by comparing us to them.’ Comments like that generally don’t bother me because I think that everyone’s opinions are valid, but something like that was hurtful to me, and it certainly didn’t help the perception of my own faith that I was developing at the time. That was an incident when I definitely felt insecure.”

However, Tirmizi expressed worry that she would be persecuted after graduating from Harvard-Westlake.

“Something that’s a little bit unsettling is that when I don’t know someone, and this will be especially relevant in college when I’m introduced to a large group of new people, I do fear that people might intentionally or unintentionally make assumptions or judgments,” Tirmizi said.

Iken has a less than positive outlook on Muslim discrimination.

“The stereotype that all Muslims are terrorists is so deeply ingrained in society, but there’s nothing that can really be done about that,” he said. “People are arrogant and don’t want to listen to opinions that are different from theirs. We are a minority. People don’t interact with us everyday, so people don’t know us. People are afraid of things they don’t know.”

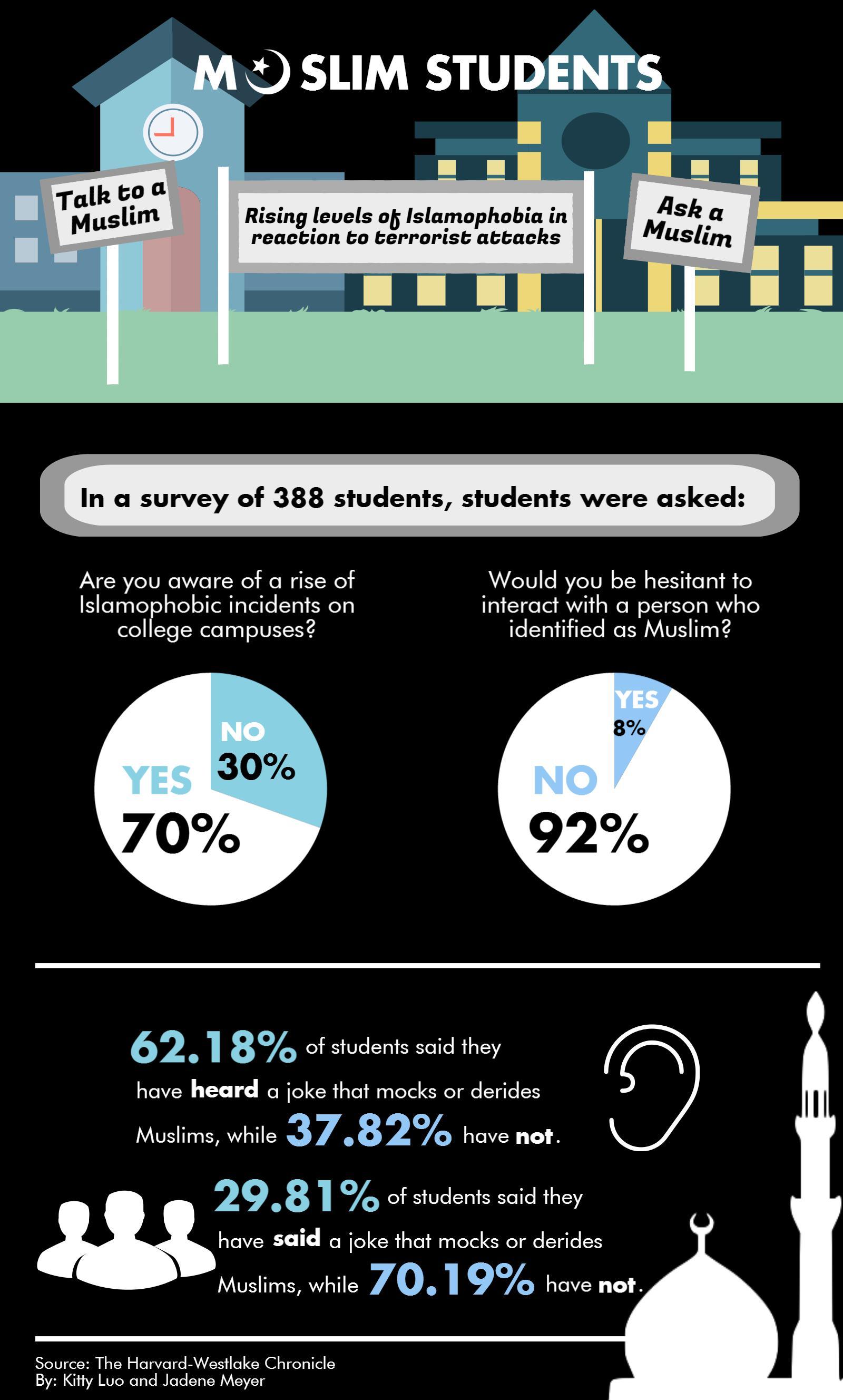

Tension on campuses nationwide is due to the increasing demand for inclusivity and tolerance. With Harvard-Westlake students leaving relative security for college, the need to expose prejudice and discrimination becomes more urgent. Tirmizi points to the actions of Mona Haydar as an example for positive and forward change. In December, Haydar stood outside a Cambridge library with signs that said “Ask a Muslim” and “Talk to a Muslim,” offering free donuts and coffee to those that asked her opinions about her faith.

“Events like that, where people can shed some light on the truth, are constructive steps in the right direction,” Tirmizi said. “Anybody who’s looking for answers should have access to them. So I think instead of speaking out in a confrontational way, sharing your knowledge with someone who you think would benefit from understanding more of the story is better.”