Among the most prominent figures on Ted Walch’s desk, which is wedged into a back corner of the drama office at Harvard-Westlake, are two transparent cases.

One is a cube encasing an old, yellowing baseball littered with faded signatures. The other is a lengthier prism and houses two shiny white baseballs which look to be in pristine condition, as though they had never even touched the dirt of a base plate. They, too, are adorned with several autographs.

In between the orbs of American pastime sits a championship ring—complete with a logo, gems, engravings and all—commemorating the Wolverines’ CIF-Southern Section Division I title-winning season in 2013, for which they were crowned National Champions by Baseball America.

“This is what life is all about,” he says. He taps the smaller case, then the larger one. “From this to this.”

The performing arts and cinema studies teacher grew up in Sedalia, Mo., a city of about 20,000 and home of the Missouri State Fair. As a child, he would lay on the floor in his house’s sunroom (“We called it a sunroom; it sounds fancier than it was,” Walch says) and listen to the St. Louis Cardinals on the radio.

“I didn’t really know what I was listening to so much, but I loved the sound of the broadcast, I liked the rhythm of it,” Walch said. “I was just really little, I just thought it sounded neat.”

The radio announcer for the St. Louis Cardinals at the time was the famed and ebullient Harry Caray, who spent the first quarter century of his 53 year-career as a Major League Baseball announcer with the Redbirds. To this day, Walch remembers Caray’s hallmark phrase which he exclaimed after every home run: “It might be…it could be…it IS! A home run! Holy cow!”

“So then I got fascinated by the game…not by the arcana, not by the details of the game, just sort of the spirit of the game,” Walch said.

Entranced by the sport, Walch went on to play the game. When he was in seventh grade, he played left field for the Rotary Rockets, a team run by a local civics club.

“I was horrible,” Walch says. “I’d be thinking of other stuff and suddenly there’d be a ball that dropped right in front of me. But I loved to bat, and I was pretty good. I was a good hitter. I couldn’t throw and I wasn’t very attentive to the game, but I’ve always been sort of weirdly fascinated by baseball.”

The fascination died down when Walch was in college—”I paid little or no attention to it,” he said—and remained non-existent shortly thereafter when he lived and worked in Washington, D.C., a city which did not have a professional baseball team at the time. (The Montreal Expos didn’t relocate to the capital until 2005, whereupon they were renamed the Washington Nationals.)

But then Walch himself relocated to the Bay Area in the early ’80s, which was already home to a thriving Oakland Athletics team, headlined by Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco, who were affectionately dubbed the “Bash Brothers.”

“I got absolutely hooked by the Oakland Athletics and the Bash Brothers,” Walch said. “I had a season ticket; I went to 44 games one year; that’s a hell of a lot of games, I had the same seat every time. I loved the Bash Brothers, they were so much fun, it was kind of heartbreaking when Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco were outed as it were.”

Canseco admitted to using steroids in an autobiographical book, which was published in 2005. In the book, Canseco identified McGwire as steroid user. In 2010, McGwire came forward and confessed to using steroids.

However, not all of Walch’s memories of the A’s are tarnished by steroid use. He was in the bleachers of the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum (now called O.co Coliseum) when Rickey Henderson stole his 939th base of his career, setting an MLB record which still stands today for career stolen bases.

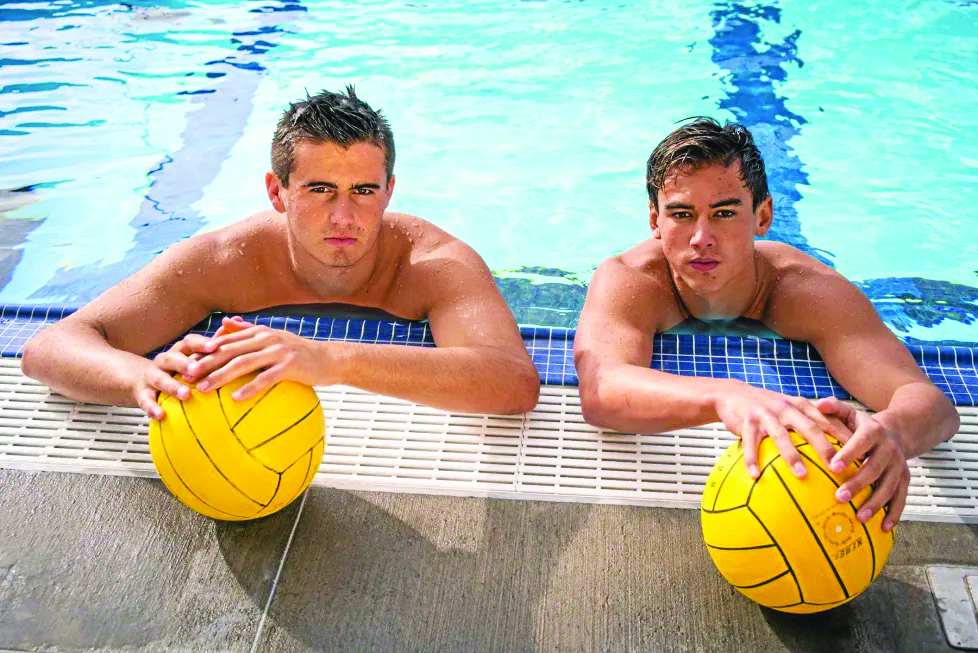

“[Henderson] was a kick,” Walch says. “In some ways Paul Giacomazzi ’16 reminds me of Rickey Henderson. He’s a good leadoff hitter, he’s scrappy and he steals.”

And yet, there were still plenty more baseball memories to be made for Walch. Giacomazzi, who Walch says is “the nicest kid on the planet,” would be a contributor to those memories.

While the Athletics were making World Series appearances in Oakland, about 20 miles away in a town called Ross, Walch was also taking in a very different level of baseball, as an “assistant coach” at the Branson School, a high school.

“My official title was ‘Spiritual Advisor’ because they needed a lot of spiritual help,” Walch says. “We would lose by scores of 12, 15, 20 runs regularly. If we lost by anything under 10 we were ecstatic.”

Walch gestures toward the faded baseball. “And I love these guys, these guys were awesome. I remember every one of them vividly…They were great kids. You get to know them in a certain way, you get to watch a pitcher burst into tears; the coach says to me, ‘should I pull him?’ And I say ‘no, his parents just arrived so…’ You know, that was my job. ”

Indeed, despite the incredible discrepancy in talent, Walch enjoyed the Branson Bulls even more than the Oakland Athletics.

“The two things that I do, other than direct plays and teach school, that I love to do in this life, that are my recreation that take me out of myself where I just get lost and don’t think about stuff, this is one,” Walch says, tapping the baseball case. “And I actually prefer it when I know the players.”

The other is going to the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

“I never loved a game any less because we weren’t quite as good say 15, 20 years ago as we are now,” Walch says. “I loved those games,

just like I love those kids on that fading, sad little baseball over there. Notice it’s got a case, too, though.”

In 1991, when Harvard School for Boys and Westlake School for Girls merged, Walch was hired at Harvard-Westlake School, and was tasked with “building a theater program that everybody could be proud of.” The theater program and the baseball program quickly became connected through Walch.

“I immediately attached myself to [the baseball program] because I had come from Branson, where it was a big part of my life there, too,” Walch says. “And I just couldn’t imagine being here without getting involved. It was a little lazier back in the early days, and we could have such wonderful things happen as happened with Frank Pfister ’04, Frank was able to play the lead in the play that I directed, Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke, and we worked that out with the coach, Tim Cunningham, who’s now an assistant coach at Notre Dame and a really lovely guy.”

As Walch developed the theater program, he got to see the baseball program develop, as well. He recalls the early days as well as the glory days.

“We came in second in a 1-0 game under the old guard, Tim Cunningham. Frank Pfister was on that team…we certainly had nothing to be ashamed of,” Walch says. “Brennan Boesch ’03, Josh Satin ’03, those were two guys we sent to the [Major Leagues]. But there’s no question, Matt [LaCour], first of all, is brilliant, and dedicated. There’s no question when we hired Matt it was a commitment, because he was a star coach when we hired him, it was a commitment to up the ante on the program, no doubt about it.”

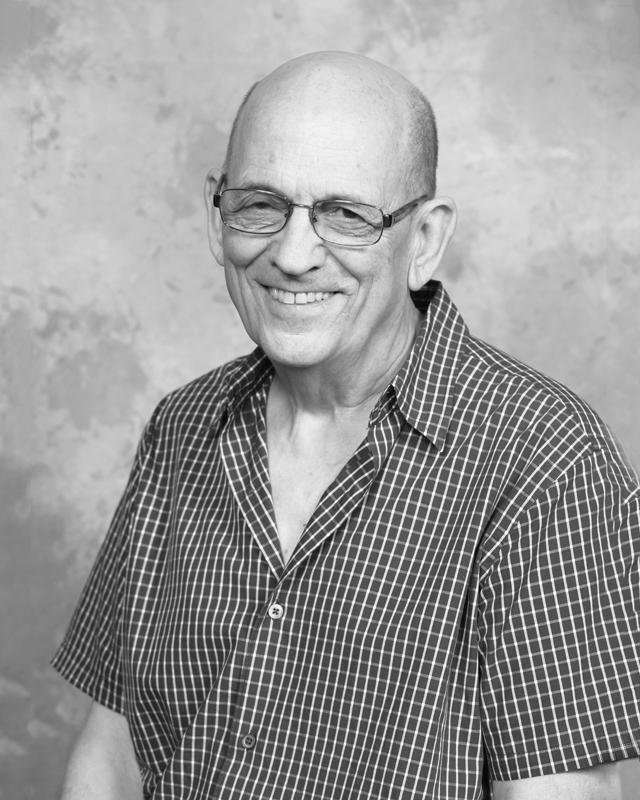

Since he was hired, Walch has been with the baseball program every step of the way. He attends virtually every home game and most road games. Even LaCour, who is now an Athletic Director, noticed his presence.

“Aside from the parents that kind of come and go through the four years, Ted’s fanatic behavior remains each and every year that we’re at school,” LaCour said. “He’s exhibited the ‘Best Fan’ attitude for the longest period of time…When he can’t make it to a game, he agonizes over it and he will let you know if you’re the coach that ‘this is why I can’t be there today and it’s killing me.’”

The “Best Fan” himself knows exactly what time every league game starts (3:30 p.m.) and admits that he’s travelled durations of up to 200 minutes to watch the team play.

“The furthest I’ve travelled was Vista…is it called Vista Murrietta? I thought I had actually left the state of California and I thought I’d lost my mind, and if Jake Suddleson ’16 had not hit that home run, it would not have been worth it,” Walch said with a chuckle “But he did. It’s so far, it’s like two and a half hours, two hours, it feels like nowhere you’ve ever been before.”

Perhaps the most memorable trip he made was to a more familiar place: Dodger Stadium. The historic 56,000-seat venue tucked away near the San Gabriel Mountains in Chavez Ravine is home of two prominent memories for Walch, each on opposite sides of the emotional spectrum.

The first is forever etched in the annals of Major League Baseball, an event Walch says was like the worst moment of my life.” A hobbled Kirk Gibson famously hit a walk-off home run off Dennis Eckersley to give the Los Angeles Dodgers a 5-4 victory over the Oakland Athletics In Game one of the 1988 World Series.

25 years later, Walch was at the stadium for “one of the most exciting days of my life.” The day Harvard-Westlake defeated Marina in the CIF-Southern Section Division I championship game.

Walch points at the larger case. “This was huge fun; I’ve never had more fun. That game was one of the great games of my life, of any level of anything, even watching Dennis Eckersley throw the fatal pitch.”

Everyone on the team received a championship ring. Players, coaches and Ted Walch.

Walch taps the case with the ring in it.

“This is always going to be a mystery to me, I’m not a stats guy, I’m dyslexic with numbers, so I can’t know [batting averages], and frankly that stuff bores me to death,” Walch says.

“What I love about this game more than anything is it has the natural rhythms of life about it…basketball is not natural, life is not like a basketball game,” Walch says. “In truth, life has its boring patches, has some down times, has moments when if you look away something exciting happened and you could have missed it.”

Walch still does his best to make sure he doesn’t look away when it comes to the baseball team. Now, he looks back at the two cases.

“Neither one is better, they’re just different. I had so much fun, travelling all over Northern California with that team. I am no baseball coach. Baseball is still a kind of wonderful mystery to me. I keep going to games in part because I’m still trying to figure them out. Because…baseball is really complicated and it’s like if you were watching a whole bunch of people play chess and you’re going ‘ooh look at this, look at that’ and you can either decide when you’re watching a game to tune into all of that and to try and figure out why this adjustment, what do they know about this hitter, why is he throwing that pitch, yada yada yada … I sometimes try to do that, and then other times you can just sit back and have a good time.”

Sitting back and having a good time—whether taking in the atrocity that was the Branson Bulls baseball team, the stunning Bash Brothers, or the talented Wolverines—that’s what watching baseball is all about. That’s what life is all about.