Courtney Nunley ’17 nervously drove through the Inglewood and Culver City area. It was winter break of her junior year and one of her first lessons with her driving instructor. The windows were rolled down when a voice outside the car caught her attention.

“Hey you, n*****,” a stranger shouted.

“After that, I was pretty distracted and disoriented,” Nunley said. “My instructor was trying to be nice and didn’t say anything, but he rolled up the windows and mumbled something negative about whoever said it to me. For the rest of the day, it stayed in the back of my mind.”

Following last month’s racist and homophobic slur controversy, the administration held meetings to discuss the event’s implications.

Affinity group club leaders said that, following the incident, there have been more school-wide discussions about diversity and inclusion.

Similarly, Black Leadership, Awareness and Culture Club leader Phaedra Robinson ’17 does not condone the use of the n-word by anyone. For Robinson, the racial slur elicits negative emotions and experiences.

She recalled being called the n-word repeatedly during a game of tag at her middle school.

“I remember being really upset but not having formed an opinion on the word and just being young and really confused about what it meant to me,” Robinson said. “I was really mad and didn’t know how to express that. I didn’t react how I would react now.”

Despite its predominance in pop culture and colloquial use by some black people, Robinson and Nunley do not condone the n-word in non-educational settings.

“I don’t think that someone of any race should say it,” Robinson said. “I don’t condone it in rap music. I don’t say it myself. I don’t really think it’s okay in a casual sense.”

Originating from the Spanish and Portuguese word for black, “negro,” the word was Anglicized during colonial America to “neggar” and “neger.” Initially used as a neutral descriptor of slaves and black people, by the Civil War era, the word “n****r” had become a derogatory and demeaning term for black people.

However, the frequent use of the n-word in rap music and informally by some black people has resulted in its pop culture relevance. The notion of black people taking the n-word as their own remains controversial within the black community.

Robinson attributed the n-word’s predominance in pop culture to misconceptions about the word and its connotations.

“I understand the fact that we’re not completely united on the use of the n-word in our own community, and that ambiguity confuses other races,” Robinson said. “It being in mainstream culture can kind of make people think that it’s okay.”

Whereas Robinson and Nunley are not comfortable with anyone saying the n-word or its use in pop culture, Brandon Brown ’18 said it can be used as a term of endearment in certain contexts.

Nevertheless, Brown does not condone non-black people saying the n-word.

“I say it, but that’s just because it’s in my vernacular,” Brown said. “I don’t say it in front of anybody but people I know will be okay with it.”

He agrees with the notion of reclaiming the n-word — taking the historical racial slur and turning it into a positive term. However, he believes there is a difference between what is called the “hard r” and “soft a,” ending the word.

“The soft a I think is used as a term of endearment. But the hard r, even if a black person were to say it, it’s just weird. It seems more rooted in oppression.”

Nunley said that the ending variants of the n-word do not change the word’s negative connotation. However, Nunley said she is less inclined to call out another black person for using the n-word.

“I feel like it’s hard to call someone else out, especially when [the n-word] should hold the same weight to you as the other person,” Nunley said. “There’s a wide array of opinions on it within the black community itself, so something that offends me might not offend another black person.”

In addition to affinity group meetings and discussions with the administration, the week after the slur controversy, Upper School Dean Chris Jones addressed class meetings and shared his personal experiences with the n-word.

“[Jones’ statements] were enlightening,” Keller Maloney ’18 said. “I had no idea of the gravity that the word itself carries. I think it only reinforced my opinion that the word should be banned on campus in any context and by any person.”

Maloney said he does not condone the use of the n-word by anyone, especially in a school setting.

“I just think that in no way in a community that’s trying to be inclusive and make sure that all members feel protected and safe, should such a hateful word, even being carried in non-hateful contexts, be used by anyone of any skin color,” Maloney said.

According to a March Chronicle Poll of 335 students, 85 percent have heard the n-word said on campus. Ninety-three percent think it should not be said on campus.

“When I think about basic profane language, it fits into that same umbrella as the rest of those words in some senses,” Jones said. “Now there’s obviously a big historical piece to it, too that vaults it into a category on its own, but it still fits into that same sort of realm.”

Outside of school, however, Jones said the use of the n-word in a social setting is a choice that black people can decide upon.

“I would say that whether it’s this word or it’s other words for people who are coming from groups who have been historically disenfranchised, if they want to reappropriate those words and use them in a positive sense, I don’t think someone can be outside of the groups and tell them what the rules are and whether or not they should use it,” Jones said.

Similarly, Liam Douglass ’18 said that, as someone not originating from a black background, he does not believe he has the authority to determine whether or not black people can use the n-word. He also said that the n-word’s significance in American pop culture reduces its weighty history.

“I think [seeing the word frequently in pop culture] normalizes the word almost as a comical thing,” Douglass said. “With my upbringing, I’ve always been told never to say it, no matter what the context.”

Maloney said he understands how the n-word can be used as a term of endearment in rap music, but hearing it used positively feels strange since it goes against what he has always been taught about the word itself.

“[The fact that] a word that you’ve been taught since at least early adolescence can never be said and is so bad is all of a sudden being used randomly and almost happily is a shock,” Maloney said.

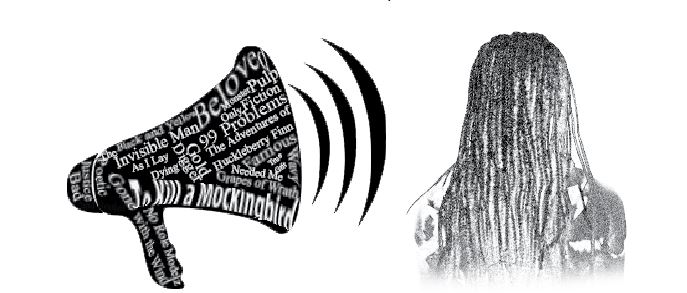

Although Douglass does not condone the n-word when said by people who are not black, he also said reading “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” during his sophomore year was an informative educational experience. According to a Chronicle poll of 335 students, 66 percent said that the school does not educate students on the history of the n-word.

The novel includes the n-word in 219 instances, often in reference to Jim, an escaped slave who accompanies Huck throughout the text, but is not a part of the tenth grade English curriculum this year.

English teacher Darcy Buck said the department made this decision because of the novel’s length, as well as to reassess the best way to present the issue of race in a classroom discussion.

“One [reason for not teaching the novel this school year] was definitely that we had been hearing that the emotional impact of the language of the text and the context of the text had been difficult for a lot of students, in particular our students of color, and in particular for our black students,” Buck said.

While Buck believes teaching Huck Finn allows students to discuss race in a classroom setting, she also said that the depiction of Jim can be viewed as stereotypical, despite Mark Twain’s intent.

Buck said discussing both Jim’s stereotypical image and the anti-racist purpose of Twain’s text can be difficult to convey to students with limited knowledge on issues of race.

“We can argue that there are ways in which Jim is depicted as the most human, the most kind, the most brave, the most generous of all the characters,” Buck said. “Yet I also feel like the ways in which Jim is valorized have to do with the way in which this black man takes care of and serves to this white boy, and I feel like those are problematic parameters for heroism.”

Nunley agreed that the portrayal of Jim in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” caricatured him as a stereotype of a black person. Additionally, she said the English and history courses could have done a better job of highlighting the accomplishments of black people.

In terms of moving forward from last month’s racial and homophobic slur incident, Buck said the responsibility for change falls to faculty and administration and should not feel like an obligation for students of color to try to fix.

“Part of what we have to do as an institution is educate one another,” Buck said. “We’re the grown-ups, the teachers, the administrators. It’s not the job of students, and it’s especially not the job of black students, to be the ones to have to take on that burden.”