Any given dance rehearsal, slam poetry club meeting or creative writing class is full of talented and expressive students who choreograph their own dances, passionately perform original poetry and workshop personal essays with their classmates. Surrounded by such energy and enthusiasm, it’s hard to notice that something’s not quite right: there’s a distinct lack of male students in all of these activities.

For example, there’s an enormous gap between female and male students regarding their interest and participation in the slam poetry club, English teacher and slam poetry adviser Eric Olson said.

“With the exception of the first year, when we had a couple of senior boys who were very interested in rap and writing, it’s been difficult to recruit boys to do this,” Olson said. “This year, we had many female students audition, we had gay and straight students audition, but we’ve had very little interest from male students in general.”

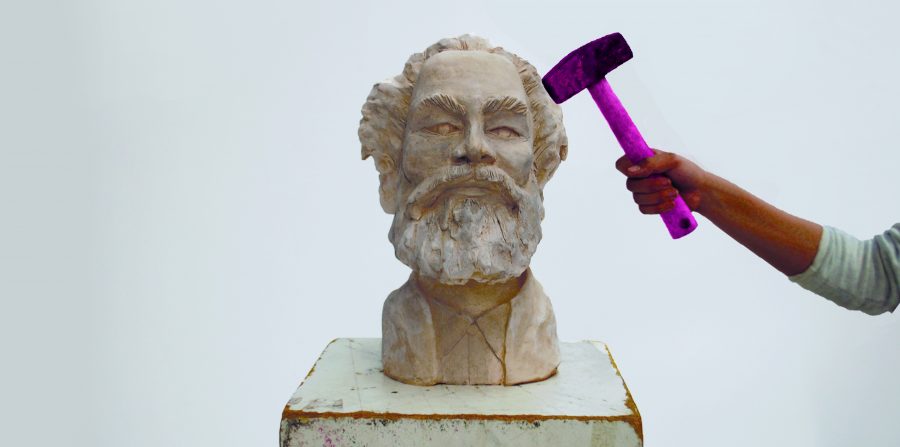

In recent years, both Harvard-Westlake students and society at large have begun to engage in discussions about the effects of sexism and gender stereotypes. The feminist movement has brought attention to the harmful stereotypes surrounding girls in STEM, for example, and as a result, the number of girls in upper-level science classes on campus has increased.

However, stereotypes about masculinity and male behavior also have harmful effects, La Femme leader Becca Frischling ’19 said.

“One stereotype that I see is that boys are generally not expected to really express their appreciation for their friends because that’s not seen as manly or tough,” Frischling said. “That kind of toxic masculinity is just another restraint being placed on people because of their gender. I think one of the goals of feminism is, yes, to focus on women’s issues, but also to ensure that everyone can live their lives the way they choose to regardless of their gender. That would apply to toxic masculinity too.”

The term “toxic masculinity” refers to the argument that traditional stereotypes of men as unemotional, aggressive and fully self-reliant can have toxic effects. These stereotypes can be seen regularly on campus, junior prefect Kevin Chen ’19 said.

“With the people I’ve talked to, especially guys, a big thing at school is that they feel like they should play sports,” Chen said. “I think stereotypes [about masculinity] have a negative influence on campus. I know a lot of kids who consider themselves less manly because they’re not athletic, and that’s not true.”

More specifically, the gender norms associated with toxic masculinity discourage male students from showing or expressing their emotions.

Consequently, dance, slam poetry and creative writing, which are activities that require students to express their emotions publicly, are stereotyped in the high school context as unmanly, Frischling said.

Matteo Lauto ’18, the only male member of the slam poetry club, said there is a stigma around boys participating in more emotional and “feminine” activities because of the expectation that boys adhere to traditional norms of masculinity.

Slam poetry club and competitive team member Jenny Yoon ’19 said that she also noticed a link between the expectation for boys to act less emotional and the low numbers of male students in slam poetry.

“Guys need to be more open to expressing themselves, such as in these creative outlets,” Yoon said. “I guess this could all tie back into the larger overarching theme of toxic masculinity–that you need to be stoic and engage in more physical activities [like sports].”

Similarly, dancer Daniel Varela ’18 cited expectations surrounding masculinity as a factor behind the gender disparity within the dance program.

“Most guys probably aren’t participating in it due to common stereotypes of dancers as being more feminine or not being straight,” Varela said. “I think that just because of that image and portrayal, people would rather be on a sports team rather than a dance team.”

Frischling said that she was disappointed about the negative impact of toxic masculinity on boys’ involvement in activities on campus.

“Boys should not be afraid to express their feelings or to take part in performing arts activities or other things that aren’t typically seen as manly,” Frischling said. “Because in reality, they should be able to express themselves and their interests whatever way they want to.”

Unfortunately, harmful stereotypes and ideas about masculinity begin in childhood and extend off campus, making it difficult to create change, Olson said.

“It’s a cultural value that probably extends beyond the activities that happen at our school,” Olson said. “In a very broad, cultural sense, emoting in poetic ways is not always seen as masculine. I think it’s something that is not valued in boys from an early age and that trend comes to an unfortunate fruition in high school.”

However, Yoon cautioned against trying to force male students to defy those stereotypes, explaining that it isn’t a strictly black-or-white issue.

“I don’t think that we should particularly force boys to participate in more in such personal activities if they personally don’t really want to engage in them, because there’s a line to cross between actually not wanting to do something and being indoctrinated into the belief that doing that kind of activity is unmanly,” Yoon said.

On the other hand, mandating some form of participation in such activities at school could actually work to lessen the impact of toxic masculinity, Tosh Le ’19, who took a creative writing class last semester, said.

“I en-joyed creative writing tremendously [but] it is certainly true that we live in a society where expressing emotion is frowned upon disproportionately for males,” Le said. “I think that having more ‘creative’ assignments in required English classes could remove the stigma associated with them.”

Lauto pointed to activities like Peer Support and slam poetry as opportunities provided by the school to change the stereotypes surrounding boys expressing their emotions.

“[The school] provides great opportunities for guys to explore more emotional and sensitive experiences,” Lauto said. “Obviously, we need to be more open and inclusive, but that mentality takes time to change.”