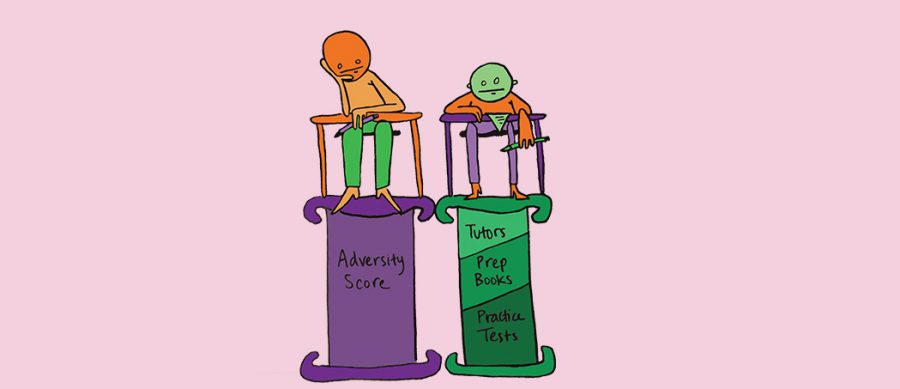

Tutoring and prep books combined, Sandra’s* parents spent $2,000 on their child to score a 1570 on the March SAT. Without their support, Sandra said she would not have been able to reach her score. Students without this support, however, have always been at an unfair disadvantage, Sandra said.

In an effort to capture students’ social and economic background in the college admissions process, the College Board will issue a new rating, widely referred to as the “adversity score,” to every student who takes the SAT beginning this fall.

The score will consider 15 different factors, including the crime rate and poverty level of the student’s neighborhood, as well as the relative quality of the student’s high school, in order to level the playing field for students with economic disadvantages, according to the New York Times.

Alex Poe ’20 said she hopes that the new score will help students of all backgrounds have a fair chance in the college admissions process.

“I think that as Harvard-Westlake students, we have a lot of privilege, and although some might say that it’s not our fault that we have privilege, we do have it, and that puts us in a significant advantage,” Poe said. “Students who are in other areas just don’t have access to the kind of resources that we have. As someone who came from public school and who has friends in many different schools throughout the area, I have so many friends who are just as smart and capable, but maybe might not come across quite as well on paper because they don’t have access to the same kind of deans and college advising that we have.”

According to a Chronicle poll of 303 students, nine percent said they believe the score will be advantageous to them, while 65 percent said it will negatively impact them.

However, the score may fail to accurately represent students’ circumstances, Otis Gordon ’20 said.

“Say you live in an affluent community; [College Board will] give you a score saying that you’re over-privileged or whatever, but people from low-income [communities] who work their ass off to go to a good school and live in a nice community are going to be at a disadvantage,” Gordon said. “Also, I feel like there’s loopholes. People who are rich [can] buy a house in a poor community and say they live there. I say there [might be people who will] take advantage of this.”

Though she believes it is important for colleges to account for the advantages that some students may have over others, Helen Graham ’21 said she is unsure how the adversity score would encapsulate other circumstances.

“Some students only have one parent present, and this sets them at a disadvantage at a young age if their parent or guardian is working full-time and can’t spend time talking or reading to their child because this offsets their development,” Graham said. “I think that there will never be a way to ensure that the standardized testing system is equal because lack of opportunity and other extenuating circumstances have such a dramatic effect on student’s performance on these tests that it is difficult to account for every possible disadvantage that some students have.”

Before the score was administered, however, college admissions officers were able to read applicants’ profiles contextually, Head of Upper School Laura Ross said. She previously worked as Associate Director of Admission at Scripps College and Associate Director of Undergraduate Admission and Director of Transfer Admission at Columbia University.

“I sort of appreciate their intent, and certainly you want every student’s application to be read contextually and understand what advantages they have, but it feels to me that they are trying to overcome the fact that [the SAT] has so much bias in it,” Ross said. “As a former admissions officer, my whole job was to read contextually. I didn’t need the College Board to give me a number. We’re always trying to look at where does this student come from and what was available. That’s already happening. Maybe it’s because I worked at private institutions that had those resources, so maybe for a big state school that doesn’t have that opportunity, this may be helpful.”

The new score may also cause more students who reside in affluent areas to take the ACT, John Szijjarto ’21 said.

“I think it’s really good that College Board is trying to level the playing field and make it easier for kids [who are] low-income or don’t have as many resources to be able to get into these really prestigious colleges, but I think that it’s going to end up with kids in affluent areas taking tests like the ACT or applying to colleges that don’t require the SAT,” Szijjarto said.

The adversity score may also place more pressure on families to send their students to SAT preparation academies, Szijjarto said.

“If you live in an affluent area or go to an affluent school, but your family doesn’t have resources to send you to get test prep from companies like Compass, then it’s going to be a lot more stressful for you because there’s that extra thing to worry about,” Szijjarto said. “Same goes for the other way around because if you live in not the best neighborhood, but your family has a lot of money, it’s easier. It’s a case by case basis, but I think overall it’s going to cause more stress.”

As someone who has taken the ACT, Paige Corman ’20 said she is glad that students will have the option to choose if the adversity score will affect them.

“I think that there will be some students who will feel that the adversity score will work against them and will take the ACT instead, but I hope they will choose which test to take based on which they feel they can perform better on,” Corman said.

According to a Chronicle poll of 303 students, 29 percent said the new adversity score will impact their decision on which standardized test to take.

Having not yet decided which test to take, Graham said that College Board’s new rating will not affect her decision on whether she will take the SAT or ACT next fall.

“[The score] would not affect my decision because I go to a private school, live in a safe neighborhood and have privilege inherently because I am white, and it is important to me that these advantages that I was born into should not put me ahead of those that do not,” Graham said.

Kelly*, who moved to a wealthy neighborhood in the beginning of her junior year, said that the score could hurt more people than it could help.

“In my case, [the score] could hurt me because halfway through high school, I moved, and the area I moved to had a higher socioeconomic status than [where I lived] before,” Kelly said. “But that wasn’t a result of my household income changing or increasing. It just happened that the area that we moved to had a higher average socioeconomic status. That doesn’t reveal anything about my work ethic, my grades or the overall adversity I face in life.”

In spite of the debate surrounding College Board’s new initiative, Ross said she believes that it will have little impact on the students at the school.

“ACT and SAT are in business competition,” Ross said. “SAT has been losing so much market share to ACT, so this just seems like another way they’re trying gain market share. I often feel that the moves institutions like the College Board make are not about serving kids, even if they say that they are. So, while I hope all admissions is contextual and kids are being seen with an understanding of all the advantages and challenges they’ve had in their lives and how they made the most of whatever situation they were in, I have to admit to feeling a little skeptical.”

*Names have been changed.