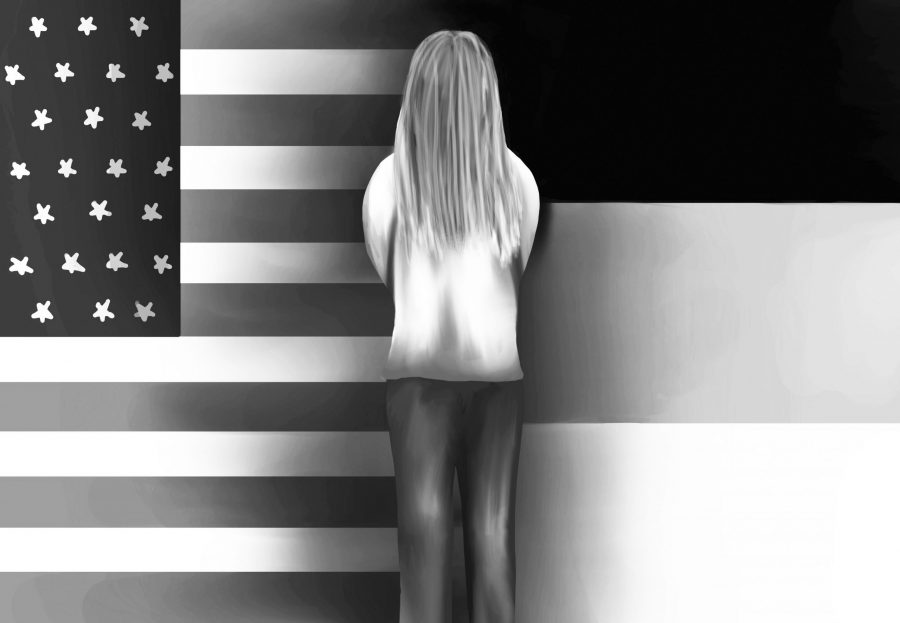

As a half-German, half-American girl living in the United States, I’ve always felt as though I live in two separate worlds. One is the world of salmon on Christmas Eve, backyard gatherings where barbecue is conspicuously absent, the smell of wet pine needles and soccer. It is the German world, spaghettieis and dirndls and alpine flowers. The other world is the American one. It is war history, economic policy, international relations and journalism. It is Washington and FDR biographies and novels by Louisa May Alcott and Sylvia Plath.

From the outside, one might look at my nationality and observe that the German world is my father’s and the American one my mother’s. After all, everyone on my mother’s side—the American one—has at one point devoted themselves to service for their country through some form of public policy. As the daughter of an American diplomat during the Cold War, my mother grew up in Poland, Switzerland, Germany and the United States, eventually settling in Los Angeles. My father was born and raised in Munich, Germany, but immigrated to the U.S. when he was 32.

I, too, always saw the German world as my father’s and the American one as my mother’s, and I struggled to determine where I would fit. On one hand, I live in America, and I don’t speak much German (only ein bisschen), so one would think I identify more with my American heritage. On the other hand, half my family lives in Germany, both my mother and father lived there and most of my parents’ friends are German. I used to think my family friends were more German than I am because most of them speak the language fluently and either lived in Germany or went to boarding school there. At family reunions, it has always been difficult for me to communicate with my father’s side of the family in their native language, a barrier I am ashamed of. I figured if I tried harder to be German, if I learned the language and memorized the proper etiquette, I would feel more connected to my heritage. But in doing so, I found that I fit into the American world less and less. I felt awkward setting the table at my friends’ houses, not knowing if I should place the utensils to the right or left of the plate, and I wanted to wake up with a sense of jittery excitement on Christmas Day like my classmates, instead of opening gifts the night before in the German tradition.

However, after years of grappling with my cultural identity, the conciliatory overlap between my two worlds started to become apparent. When I began to look at my identity more closely, I learned most people never inhabit a specific world. Rather, their whole lives are an amalgamation of different experiences in different places. For example, my mother grew up abroad as an American expatriate in Germany, while my father has been a German immigrant in America for 20 years. After 17 years of feeling out of place in both worlds, I have finally come to terms with my identity. Spending time with my American family inspires a strong sense of patriotism in me, and visiting my father’s family fills me with pride of my German heritage. Now, I think that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Instead of believing my nationalities are mutually exclusive, I’ve discovered they’re complimentary. I know I am fortunate to inhabit two worlds, two histories, two sets of values. I am lucky to view the world through bifocal lenses. I value the contrast and live in the overlap. I’ve learned to revel in my duality.