By Alex Leichenger

Erin Creznic is the last of a dying breed at Harvard-Westlake. In the mornings and afternoons, she goes by Ms. Creznic as an English teacher on the middle school campus. When her day in the classroom ends, she drives to the Upper School, she steps onto Ted Slavin Field with her field hockey players and becomes Coach Creznic. Creznic is the only person at the school who holds the dual titles of full-time teacher and varsity head coach.

But there used to be many, many more in the assistant and head coaching ranks. Science teacher Jim Brink used to coach baseball. Middle School English teacher Jennifer Dohr coached tennis. History teacher Greg Gonzalez coached football. History teacher David Waterhouse coached basketball and tennis. Head of Upper School Harry Salamandra also coached tennis. French teacher Geoff Bird coached cross country. Math teacher Kanwaljit Kochar was a golf coach, and Chief Financial Officer Rob Levin a football coach. Math teacher Jacob Hazard was on the baseball staff, and history teacher and current JV assistant Larry Klein was a varsity basketball assistant. Track and field coach Jonas Koolsbergen and former softball coach and current athletic director Terry Elledge both used to teach history.

Now Creznic is the only varsity head coach still teaching, but it is no accident that the teacher-coach title has become nearly extinct at the school. Head of Athletics Audrius Barzdukas believes it is almost impossible to find someone who has the time and ability to prepare for both scintillating classroom lectures and an intense high school athletic schedule.

“Our take on it is that it doesn’t really have to do with the word faculty or coach … it has to do with answering a question,” Barzdukas said. “When you stand up in front of that class, whether that class takes place on a field or in a classroom, do you know what you’re talking about?”

For some coaches, that means numerous hours during the week spent watching game film, diagramming strategies and running practices, not to mention the games themselves.

Creznic acknowledged that field hockey is different from most sports because she does not have to scout opposing teams as extensively.

But based on his own experience, Gonzalez, who coached freshman football from 1994-2001 and varsity from 2002-2004, does not believe it is impossible to prepare for both the week’s game and the next day’s class.

“There’s this belief that there just isn’t time [to be a teacher-coach],” Gonzalez said. “But if I had 50 guys on the team and 15 of them were going to be signed to play Division I football, I don’t know if it would matter if I was teaching high school history or not.”

For Gonzalez, becoming a high school football coach fulfilled a lifelong dream. He ran track and played receiver, cornerback and kick returner at Cantwell High School and later at Columbia University before becoming a sportswriter for The National and Los Angeles Times.

“One of the things that took me back to coaching and teaching was, when I was covering the California Angels, I was flying from Detroit to L.A. … and I was looking down out of the window, and I saw little glowing pearls, these little strings of pearls, and they were all high school football stadiums,” Gonzalez said. And I sort of just longed for a time when I could get off a plane and get down on those fields.”

Gonzalez said that doubling as a teacher and a coach strengthened his relationship with players. He recalled instructing future Stanford long snapper Brent Newhouse ’03, at the time a Wolverine offensive lineman and AP Art History student, to “assume a contrapposto pose” in pass protection.

“Knowing what they were doing in the classroom helped me relate to them,” Gonzalez said. “It helped me understand what it was like. Not that I made it any easier on them, but when I asked them to come in and lift weights at 7 in the morning or 6:45 in the morning or to watch film on their optional time, I knew exactly what the hardship entailed.”

For Creznic, seeing the different sides of kids as students and athletes can be helpful in both teaching and coaching.

“It’s great when you have a really quiet kid in class, and you don’t know why she’s so shy, but she’s one of the most tenacious out on the field,” Creznic said. “You just get to see a different side of the students. And I think it’s also valuable because if I have a student that’s really quiet in class but see how aggressive she is out on the field, I can kind of jokingly encourage her to act more like she does on the field.”

Klein, a boys’ basketball assistant for four CIF championship teams from 1998 to 2008, believes that private schools originally established a tradition of finding “renaissance men” adept in the classroom and on the field.

“Certainly athletics have changed since then, and maybe we’ve reached a point where just perception-wise, that that can’t be given a go,” Klein said. “But I don’t think it’s been proven that you can’t have a smattering, x-percent of your people, who still create that bind within the community that ties the community together.”

At the very least, Klein said, it would be beneficial for varsity teams to have assistant coaches who are also full-time teachers, as he was for many years.

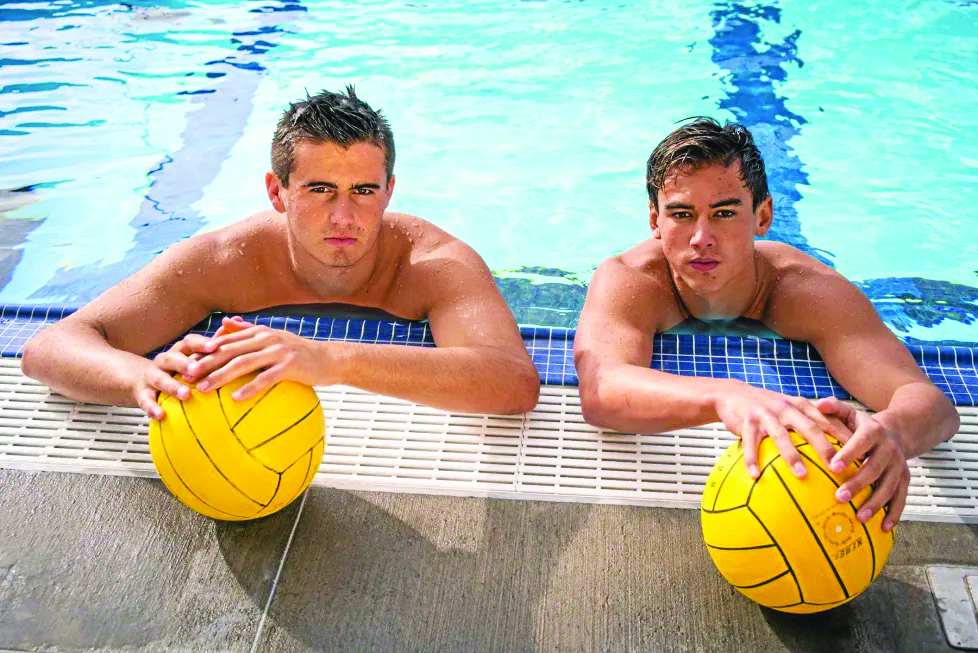

Gonzalez, whose daughter Bella ’12 started for the CIF champion girls’ water polo team, plays that role to an extent as the team’s Chef d’Equipe, assisting Head Coach Robert Lynn with administrative duties and parent communication. Though Gonzalez downplayed his impact as a “glorified team manager,” he pointed out that Lynn and some other Wolverine varsity coaches, like girls’ basketball coach Melissa Hearlihy, are able to establish excellent relationships with their players without also knowing them from the classroom. But Gonzalez and Klein agreed that it generally helps more than it hurts to have teacher-coaches, and sacrificing victories is not an inevitable consequence.

“I think everybody’s coming from the same place—that the ethic of this school is to be the best, and the question is: What’s that conceptualization of the best?” Klein said. “And certainly, if you’ve seen me coach, it’s not about minimizing wins and losses because I’m a big believer that there’s a tangibility to success. But it’s a question of, can it be accomplishable in a way that enhances the whole of the school?”

By the same token, Klein believes that successful coaches can also be strong educators.

“[At] our rival school Loyola, their basketball coach [Jamal Adams] is an outstanding classroom teacher,” Klein said. “And that’s not speculation. I know him; he’s a super-sharp guy, Columbia grad, successful businessman, and he had a personal moment in his life because of tragedy in his family that he devoted himself to kids … and he’s a phenomenal teacher. Now again, that might be more anomalous than commonplace, but heck, we always pride ourselves at Harvard-Westlake of being the successful anomaly, that we strive to find the best. And in this case, wouldn’t that be the best of both worlds?”