Let’s Talk About Sexualization

Oversexualization in the media has proven to be increasingly problematic. Students discuss social media’s impact on mental health.

Chloe Schaeffer '21 and Sydney Fener '22

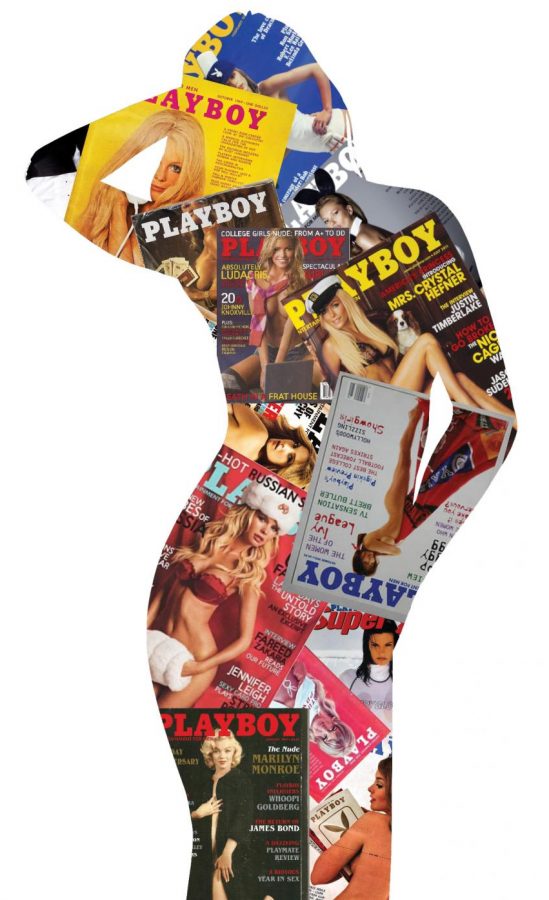

Silhouette of a women featuring playboy magazine covers sexualizing women

March 24, 2021

“I’m not looking, are you looking?”

“They looked at me first, I swear.”

Women experience oversexualization from men in the media

When Ash Wright ’22 opened the comment section of a TikTok video featuring an underage creator wearing a bikini, she stared for a moment at a series of comments posted by men insinuating their sexualization of the young woman’s body before closing the app in disgust. Wright said coming across these comments is not a rare occurrence on any social media platform she uses. She said she believes these types of comments are a direct result of the “male gaze,” a term coined in 1973 to define the phenomenon of men projecting their sexual desires upon women.

“People talk about the female gaze versus the male gaze, but I feel like men will over-sexualize each other just for fun, as a joke,” Wright said. “Boys will comment on other boys’ posts, but it’ll be totally joking. But for women, when [men] comment, it’s just really gross and obscene.”

Like Wright, Savannah Shaub ’23 said she will often scroll through the comments on a female celebrity’s Instagram post and find an alarming number of male comments sexualizing the celebrity. Shaub believes this over-sexualization is responsible for most of the body-image issues that women experience on social media.

“I think that the sexual desires of men are the main reason for women’s insecurities, and that’s especially because men have all these needs for how women physically look,” Shaub said. “You have girls who grow up with this indoctrination of needing to fit this beauty standard. And then they tell their daughters and younger generations that they need to fit this beauty standard the mom had to fit. So it’s a cycle of [the] younger generations becoming their mothers and grandmothers, all of [whom] were following ideas that came from men.”

Women and men are sexualized differently in the media

Shaub said she believes men’s systematic sexualization of women outweighs anything men experience in media. A 2011 study conducted by the University at Buffalo examined the content in The Rolling Stone, a magazine owned and run primarily by males. The study concluded that on average, 83% of women featured in the magazine were sexualized, in contrast to 17% of men. It was discovered that within those statistics, women were 1000% more likely to be featured in “hyper-sexualized images,” defined as images objectifying the subjects by portraying them as “ready and available for sex” rather than “sexy.”

Olivia Smith ’21, co-president of the EMPOWER Club, an organization dedicated to uplifting women, said she views sexualization in social media as an issue that affects both men and women. Still, she believes the historical power dynamic between genders has been translated into the culture of younger generations. Smith said the inherent inequity of this traditional dynamic is largely responsible for higher rates of female sexualization.

“Both men and women are sexualized in the media, a phenomenon that is grotesque and predatory,” Smith said. “The difference is the power imbalance. Women have been systematically oppressed, harassed, silenced and belittled, making the degradation in the media even more poignant and harmful.”

The oversexualization affects women’s mental health

Research published by the American Psychological Association addressed the cognitive and emotional consequences of sexualization in the media, specifically regarding women. The study suggested that the repercussions of consistent sexualization of women often include development of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression and eating disorders.

Shaub said she often feels as though social media negatively impacts her mental health. Even when she is not witnessing or experiencing overt sexualization in the media, she said the effects of it still linger in her daily interactions on Instagram.

“It just makes me feel really bad about myself pretty much every single day, ” Shaub said. “If I’m sitting in bed, and then I see a model in a bikini, it’s not great for my mental health. I think that the worst part about social media is how addicting it is. And most of our generation is so addicted to the point that even if we want to give up, we can’t because it’s been a part of our lives for so long. And so we get these feelings of depression, feeling bad about ourselves, anxiety or whatever feelings we have that come from our insecurities projected through social media.”

Shaub is not the only one experiencing the negative effects of constantly using social media. EMPOWER Club co-president Maddie Boudov ’21 said she often gets caught up in unrealistic beauty standards, and she expanded on certain consequences she has seen regarding declining mental health.

“So many of the beauty standards that are pushed to young people are very unrealistic, whether it’s due to [the use of] Photoshop and editing or standards being set by people whose job it is to maintain a certain physique,” Boudov said. “[This makes] it impossible for most people to live up to these expectations. This can have a wide array of effects from simply feeling bad about oneself to serious body dysmorphia and really serious negative self-image. It really just leads to an overall sense of inadequacy that I think is really harmful to young people.”

Psychology Teacher and Head of Peer Support Tina McGraw ’01 said teenagers fall into the age group with the highest chance of facing severe psychological consequences because of overexposure to media. She said issues with body image often reflect adolescent insecurities heightened by the media.

“The most common manifestations of [adolescent] insecurity are likely disordered eating patterns, low self-esteem and feelings of not fitting in with others in their age group,” McGraw said. “There have been many studies in the last decade that have examined how social media influences body image in adolescents. Most of those findings show that it is the amount of exposure which predicts the negative effects.”

Men and women experience different beauty standards

Psychologist and Ph.D. candidate of Mass Communications Stefanie E. Davis researches the repercussions of young adult exposure in sexualized media content. In one study, Davis differentiated between the psychological effects on men and women and concluded that female and male body parts are talked about in different ways. While her data shows a trend of audiences viewing the male body as desirable, female bodies are often objectified. In her published study, Davis argues specifically that media sources often portray the male chest as a desirable trait and women’s breasts as shameful.

In alignment with Davis’s research, Boudov said in her experience, beauty standards on social media are harmful toward both men and women.

“I constantly see the media telling girls that they need to be smaller, skinnier [and] happier,” Boudov said. “I see the exact opposite for boys, [who] they need to be taller, bigger and stronger. Although these are two opposite ends of the spectrum, they are effectively doing the same thing to both boys and girls: pushing a physical expectation that is challenging, if not impossible, to achieve.”

Boudov said that while sexualization and objectification in the media has impacts on both men and women, society’s beauty standards have greater psychological repercussions on women and girls due to the constant and negative attention their bodies receive.

“There is always a tabloid or headline about someone gaining some weight and wearing a bikini to the beach or so and so’s ‘new beach bod,’” Boudov said. “It frequently seems like women come under scrutiny for anything they do, whether society deems it as positive or not. I think that it leads to the self-perception of young girls to often be very tied to the praise of others and external validation.”

McGraw said she is optimistic about the future of the body positivity movement. She said although there is still room for growth, media sources’ attempts to move past their histories of hyper-sexualization are positive steps toward the production of less destructive content.

“I have noticed a significant shift in awareness over the last [few] years as people begin to push back against the narrow lens of advertising ideals,” McGraw said. “Companies are portraying lots of different types of bodies, and many are discontinuing the practice of editing images with Photoshop. These changes will eventually add up to a new awareness for young people as they continue to consume media images.”