I was gone for two weeks. Many didn’t notice. While away, I rediscovered what I call “the gap” and have consistently been queried about whether my father exists. He does.

I kissed my father’s bald head to make sure. He was a Navy mechanic from 1954, when he left rural Middlesboro, Ky., to escape a coal mining fate and traveled the world until 1975. I wear his naval tags now because I committed to fight for him. Sadly, he, like so many others, has fallen into the gap. More on that in a second.

After nearly a decade of estrangement, I became my father’s caregiver following his dementia diagnosis. Police found him roaming dark, morning streets. This wasn’t the first time. The officers took him to the hospital for safety precautions. What’s scarier than this is the shift from his home where he was no longer safe into “a system” that makes it challenging to find a new, peaceful place to call home. To avoid the gap.

The gap has at least two meanings. Neither has anything to do with commercial clothing but necessitates a courageous conversation about and a reckoning with capitalism. About how we choose our passions and pursuits and the people they impact. Relearning these meanings through the gap is reshaping my life’s purpose. Yet, this phenomenon reinforces how I have known the U.S. for much of my life. From a gap — successes and all.

The first meaning of the gap defines someone who doesn’t earn enough money to pay directly for quality healthcare. Or a person that makes (or accrued) too much money to qualify for Medicaid. My dad is wedged between these poles. He’s also stuck with a family who can’t afford to pay for quality healthcare: retirees on tight budgets, some grappling with health issues; those paying mortgages; or like me, aspiring to have a mortgage to give property to my hypothetical family. In so many ways, we are each stuck in the gap with my father.

The gap in its second meaning is a place and an idea for most. The Cumberland Gap, bordering rural Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky, is home to earnest people and gorgeous countryside. Also residing where my dad was born and chose to retire is poverty, a lack of easily accessible healthy food options and a dearth of industries. Those that once afforded consistent living wages like coal mining.

I know places like this because of my mother’s hometown, Eden, N.C. There, FieldCrest and Budweiser moved out. Though Duke Power remains, allegedly poisoning the water supply with waste, causing cancer. When these industries departed, the rural working-class American Dream went in tow. The people in these places are real and genuine, and their options, of no fault of their own, having been born and raised in the gap, are often lacking. They are stuck in some ways, too.

Oftentimes, we don’t think of Black people in these gaps. Or about Black Vietnam veterans who contributed to and benefitted from a middle class economic boom during the 1980s, of which we may never see again. Who left Silicon Valley in its heyday to return home and found themselves stuck in the gap. Their stories are either not told, lost or ignored. Maybe this is a start to reclaim that loss somehow. To tell a story that sticks.

The gap is person-made. It is not a natural occurrence that wreaks havoc on people (though modern abnormal weather activities make me nervous and are person-made, too — I am certain the notion of the gap fits here as well). What I am writing, then, is that if the gap is person-made, there’s something we could do to face it head on if we so choose.

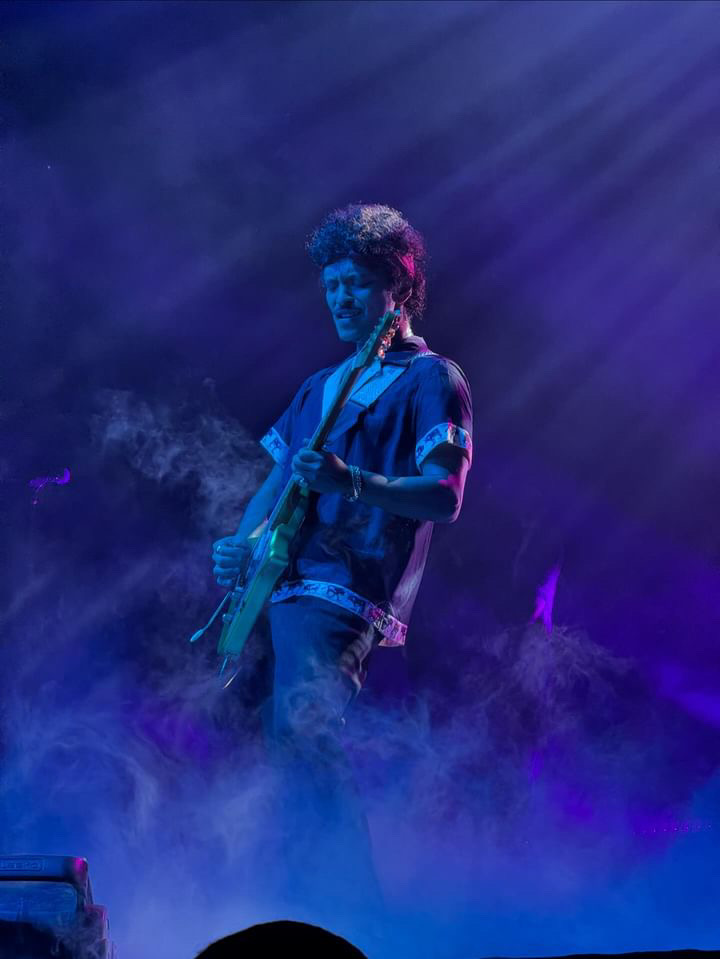

Black activist-poet Gil Scott-Heron remarked in an oft-quoted poem of the same name that, “The Revolution Will Not be Televised” (1970). This line is uttered so frequently but misses the essential point he makes near its end: “The revolution will put you in the driver’s seat.” My revolution is to resolve the gap in my father’s life — that is, if it doesn’t swallow him first. I plan to summon the energy thereafter to address the gap, however it manifests, in other people’s lives. Maybe you could do the same.

For what I know is that to be seen by someone, to see them, is a revolutionary act, a choice. We could choose to reckon with the gap that someone faces. I imagine, for instance, many unhoused people faced what my father currently finds in front of him. What I find in front of me.

To commit to something bigger than yourself addresses the gap. Gets you in the driver’s seat. You are needed for grander purposes more than you currently know. Hopefully, we as adults prepare you, our students, for such revolutionary choices. That’s my hope and my ask.