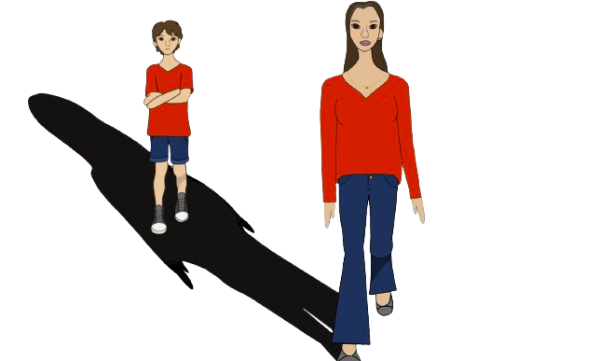

Christian Horry ’24 looked around the room and saw his dad and his old co-workers. For Horry, his dad’s old co-workers aren’t just friends from the office — they are former players for the Los Angeles Lakers who helped the team win three straight National Basketball Association (NBA) titles from 2000-2002. Horry, age four, had just seen his dad, seven-time NBA Champion Robert Horry, retire from the NBA. While he was in that room, surrounded by NBA Champions, Horry knew that the expectations were high. Even though his dad never told him he had to play basketball, in that moment, he felt the pressure of his father’s achievements looming over him.

Horry said that even though he was not able to see his dad play very much in the NBA, it drew him into basketball.

“I was born in 2005, and he retired in 2009, so I didn’t get to see a lot of [his career],” Horry said. “But I definitely felt the impact of it growing up and of all the people I would be around. It was cool, and it made me fall in love with the game of basketball.”

Horry said playing basketball with his dad has brought them a lot closer, despite Horry feeling a need to live up to his father as a kid.

“I used to feel a lot of pressure when I was younger,” Horry said. “But now that I’ve grown up, it’s not that much pressure because my dad has always made it clear that he doesn’t care how I perform in basketball. He just wants me to do well in life. We spend a lot more time together because instead of me being in the house playing video games, we will be in the gym hooping together.”

While some parents pass down their love of a sport to their children, others pass down their worries and stress. Kids with a parent who suffers from anxiety are up to seven times more likely to have anxiety, according to the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Additionally, almost one-third of sophomores and juniors at the school said their parents make them feel like they are not doing well, according to the Authentic Connections survey taken by the entire student body. Carson* said his dad often takes out his stress onto him.

“My dad will pressure me about [school work], and I’ll say ‘I’m doing it,’” Carson said. “The way he deals with his anxieties is by managing other people, and oftentimes, that’s me getting managed. That affects me. It has made me a much more anxious person and distanced me from him a lot.”

Upper School Psychologist Emily Joyner said she sees the results of the Authentic Connections survey reflected in her talks with students.

“The results from the [Authentic Connections] survey represent what I’ve heard from people about how it feels when parents are super invested in their kids getting certain grades,” Joyner said. “That pressure can sometimes lead to more avoidance of tasks and procrastination. Then, I can see it going in the direction where the [involvement] is not conducive to being able to achieve those goals. Parents being so invested in grades can make students feel like they are not acknowledged for their humanity and who they are as a person. It is reduced to equating self-worth with grades.”

Joyner said it is important for parents to offer their children support as they go through school.

“There’s a balance between being over-involved where it feels like they’re almost sitting next to you at the desk in class versus that more removed experience,” Joyner said. “Somewhere in the middle seems best. If the parents aren’t involved in the school process at all, a student might feel [the lack of] an anchor and some support structure. It’s nice to feel like someone is curious about how you’re doing without being overly invested in the outcome.”

As opposed to some who feel that their parents are too involved, Nora* said her distant relationship with her parents has made her a more self-sufficient person.

“My parents haven’t played a huge role in my life because they haven’t been that present,” Nora said. “I honestly like the person that it has made me, but it’s very different for a lot of people because my parents didn’t really do a lot of stuff for me. From a young age, I was managing all my own stuff. The absence of my parents has made me grow up very fast, which has shaped me a lot.”

George Ma ’25 has a similar experience, as his mom is a Professor of Economics at Peking University in Beijing, and his dad is an architect with business around Europe and Asia. Ma said his parents often being away has made him self-sufficient, but it can also be difficult.

“I have more individual skills and am more independent as a person because of them being away,” Ma said. “It’s kind of sad how they’re always away, but I get to call and FaceTime them a lot while they are gone and look forward to when they are coming back.”

Another potential cause of anxiety in adolescents is comparisons to their siblings. Children who receive less affection from their parents in comparison to a sibling become more likely to commit vandalism, violence and theft because of the damage to their self-perceptions, according to the Behavioral Science Institute. Joyner said being compared to other people can lead to a reduced sense of individuality.

“Comparison with others stifles personal exploration and finding out what your interests and values are,” Joyner said. “Everyone learns differently. Everyone has a different relationship with their academics and what they’re interested in. And if you’re being compared to one template, it’s pretty stifling.”

Nora said her dad often sets expectations of her relative to her older siblings.

“My dad tends to compare me to my other siblings a lot,” Nora said. “My mom does not because she’s a psychiatrist and understands how things she says affect mental health. My dad does [compare me] a lot, which kind of sucks, and it has definitely strained my relationship with him.”

Joyner said that parents can impact how their kids deal with important events in their lives, and this can be seen in kids relationships with food and their feelings.

“Often, the way we handle emotions and experiences is modeled by our parents,” Joyner said. “We can see that come up through relationships to food. Also, seeing how parents handle conflict with each other is how we learn what to do with our own emotions. How we deal with emotions and eating disorders can absolutely be an intergenerational process.”

Nora is spending her junior year away from home and said her independence and life at home motivated her to spend a year away.

“The fact that I readily packed up and moved across the world without my parents was definitely shaped by growing up fast,” Nora said. “It didn’t feel as much of a change compared to a lot of my friends who are also here. I wanted to be grown up for a long time, and I want my career to start. Also, my parents got divorced about a year and a half ago. My home life was kind of a disaster last year, so I wanted to leave for a bit.”

Nora said being abroad has led to her relationships with her parents to evolve.

“When I saw my dad for the first time since I left, it was definitely easier to be together,” Nora said. “My dad and I have a very weird relationship, but because we spent so much time apart, we weren’t fighting about anything. With my mom, I’ve never been that close with her, and being abroad has made me appreciate her more.”

Ma said he can stay close to his parents even if they are not in town a lot.

“In the end, I love my parents and they love me,” Ma said. “Even if we don’t spend that much time together, the moments that we do get to share keep the bond strong. We love going out to dinner, and these memories make up for all the lost time.”

*Name has been changed