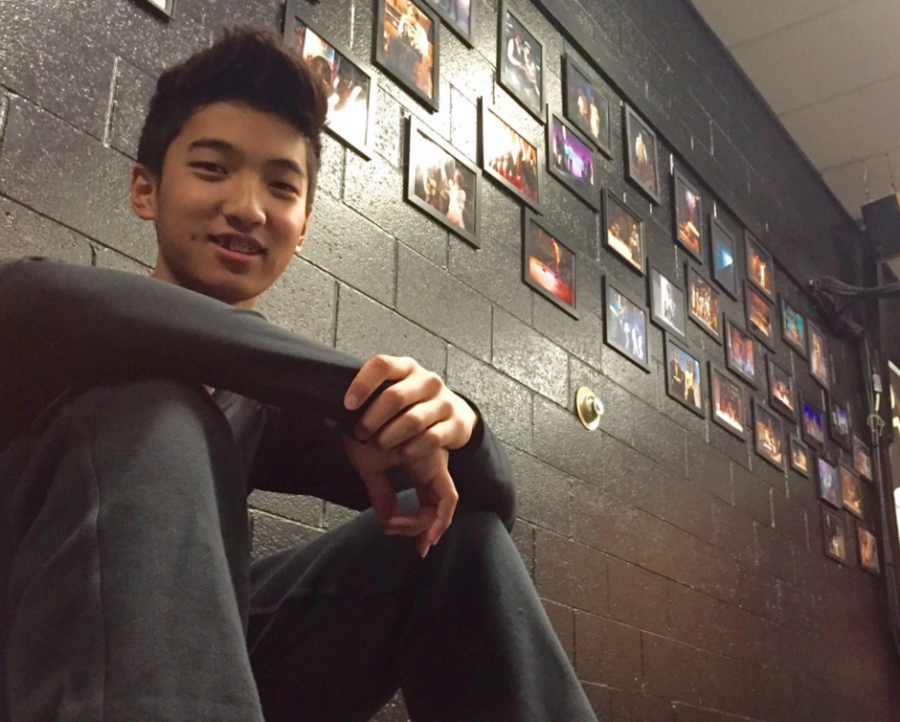

His heart was beating out of his chest and sweat was dripping from his forehead. Justyn Chang ’18 had never been more nervous. He considered running out of the small, damp room, but running out of the room would also mean running away from his dream, which was only an arm’s length away.

Singing was not always his passion. He has been a baseball player since he was three, spending his days pitching, hitting and fielding. But two years ago, everything changed.

Chang is one of the few in an elite group of teenagers who made it past a grueling audition process and signed a contract with a Korean entertainment agency. Korean pop music, or more colloquially known as K-pop, is a bigger industry than most people imagine: it has been commonplace in Asia since the 1990s, and in the last few years has risen to global prominence with the release of Korean singer Psy’s Gangnam Style, which became a staple on every pop music station and is now the most viewed YouTube video.

Two years ago, a family friend of Chang’s had shown a picture of him to a friend in the K-pop business, and he was brought in for a camera test. There, he discovered he liked being in front of the camera. However, he was still uncomfortable with his singing and dancing.

When he was told to come in for the camera audition, he started practicing his singing and dancing every day in preparation for his official audition. He had a goal in mind. He wanted to reach the top.

By doing the camera test, he was lucky enough to skip what thousands of vying teens refer to as the “dreaded first audition.” Of those thousands, about 20 make it to the next round of tryouts. This was where he got to start his audition process.

He walked into his first official audition (the second for most others) shaking. He would be performing in front of four executives, and a video of his audition would be sent to Korea for review. Aside from on the baseball diamond, he had never performed in front of anybody before.

Only two or three people made it past this round, and he was one of them. Though he was not yet completely comfortable with his skills, Chang was ecstatic upon hearing the news. He began to practice his singing and dancing for a few hours every day, dedicating himself to the art.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/237056988″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Since the agency executives had liked his audition, he was soon told he would have to go to Korea as a trainee. He was scared. “Do I really want to do this?” he questioned.

Despite his uncertainty, he went to Korea for the first time during winter break, alone. Chang described his stay in Korea as a series of constant auditions, one of which was in front of a top agency executive.

This time, he was more comfortable, feeling like he was made to perform. Soon, he signed a contract with a leading company which he declined to name.

“Being signed by the company is very special to me. K-pop is the epitome of Korean culture, and to be a part of it means a lot,” he said.

This past summer he further invested himself in the art by spending three months in Korea to train, unversed in the language and unfamiliar with the country.

Chang said his training life was hard. He didn’t go out much except for to go to and from training, and when he did, he had to wear a mask to hide his face from the public, as K-pop officials did not want their trainees’ faces to be seen in public while they were working on projects that might be released to the public.

During his time there, he trained seven days a week, with the exception of one Saturday every few weeks. From 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. he went from training session to training session, improving his singing, dancing and rapping. After the training, he worked on and practiced his language skills until 1 a.m.

He remembers sitting on his bed alone on the night of his 15th birthday. Fighting back tears, he had reminisced about times with his family; sounds of laughter and happiness. That day, all he had received were a few happy birthday messages from his fellow trainees. He recalled how much he wanted to go home, how much he missed the comforts of home.

“It was lonely and hard on the body and emotions,” he said. “At times, it was hard to choose not to quit.”

Chang felt as if he stuck out like a sore thumb in the training. He came from a vastly different world than the other trainees: they were not as privileged as he and K-pop was their only chance at making a living. The cultural mindset was incredibly different, he said, as he described the other trainees as “gangster.”

“The social differences were obvious. Unlike the other trainees, I come from a well-off background; I had it much better than them,” he said.

Although the trainees were not encouraged to quit, the option was always available. The agencies want the most dedicated kids, the ones who will stick through pain and all. Chang believed he was one.

He persevered and by the end of the summer, he loved what he was doing. He said he wanted to delve deeper into the K-pop realm.

Before he had to return home, his company presented him with three options: quit, go back home but return during breaks to train, or stay indefinitely.

Chang and his family made the decision for him to continue his education in Los Angeles, and spend time in Korea during his breaks. He certainly didn’t want to quit or to be left without options in case his K-pop career didn’t work out.

He said the support of his family has been instrumental in letting him pursue a career in this field. Both his brother and his mother expressed their support.

“It’s important to do what you love for the rest of your life, so if this is Justyn’s passion, then I support him,” his mother Stacy Chang said.

To date, Chang has starred in some dance videos, songs, and a photo shoot not yet available to the public, though he says he is just getting started. Ultimately, he would like to become a prominent figure in the K-pop industry.

“It would be cool to become a star,” he said.