Three months ago, Paige Howard ’17 committed to University of Pennsylvania for soccer, essentially finishing her college process months before juniors had even started to put together a preliminary list.

“It feels good to have a sense of knowing kind of what’s in the future, but I’m still stressed because I need to make sure I keep my grades up and everything,” Howard said. “But it definitely feels good. I feel very lucky to be in the position I’m in.”

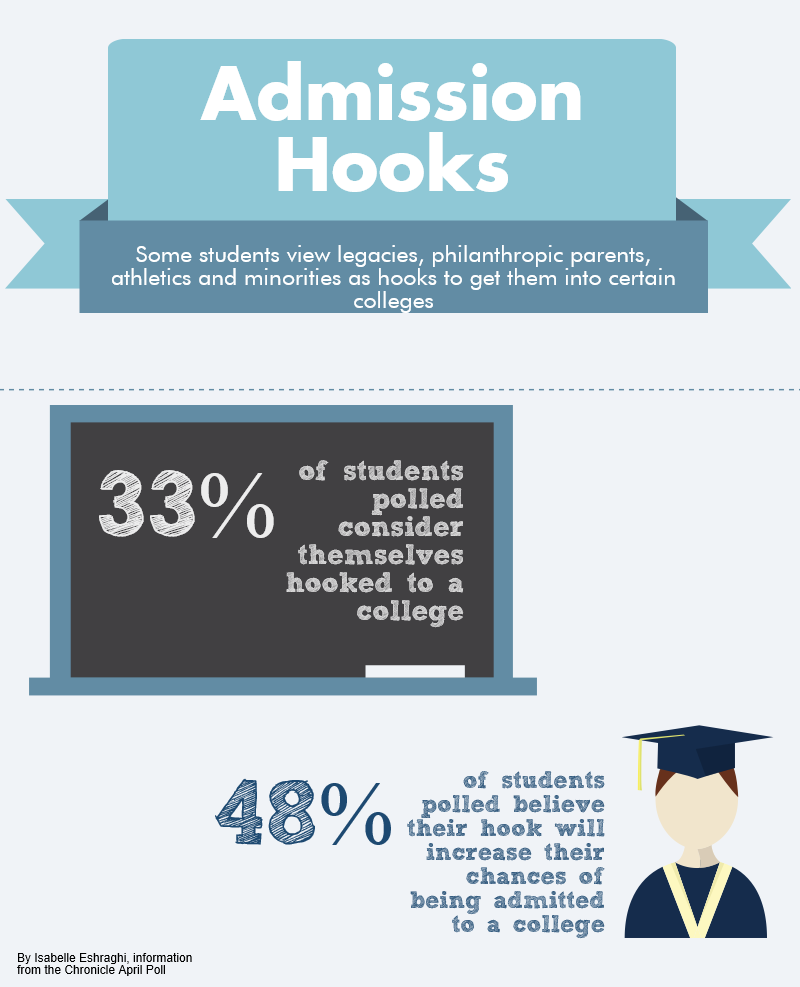

Howard had one of the four most common college admissions “hooks,” characteristics or activities that universities look for in applicants other than grade point average and standardized test scores.

The most common hooks include athletics, being a member of an underrepresented racial group, legacy and parents who have been philanthropic towards charities, high schools or colleges, but the effectiveness of the hook depends on the particular school the student is applying to, upper school dean Kyle Graham said.

“A kid is not hooked,” Graham said. “A kid is hooked at a particular school.”

Like Howard, student-athletes may visit colleges during their sophomore year to meet with coaches.

Graham also said that the institutions look for specific goals to be met when it comes to hooks, and so not every varsity athlete or racial minority may be hooked at every school.

He named California Institute of Technology and Massachusetts Institute of Technology as an example of a school where Asian-American students would not necessarily be hooked since both schools have student bodies of about 25 percent Asian students.

“So take an Asian student applying to MIT,” Graham said. “I don’t think they’re hooked at MIT. But take that same Asian student applying to a small liberal arts school where there’s only two or three percent Asian students, then they might be hooked.”

Senior Associate Director of Johns Hopkins University Undergraduate Admissions Shannon Miller said that institutions consider hooks in different ways and that for some schools, even hooked students must meet other standards to be admitted.

“At some institutions, [hooks] might be highly important, and at others, they might be a thumb on the scale – just a little [factor] that could tip you over,” Miller said.

At a Division I school, she said, a student athlete’s athletic ability may be the primary factor driving his or her admission, but at a Division III school, the admissions office would look for student athletes who also meets their academic standards.

“That is not to say that Division I athletes aren’t [also academically prepared], but there are different processes at different schools, so that’s something that I would really encourage students to talk to admissions reps about and find out what types of roles [hooks] play at particular institutions,” Miller said.

Some students do not believe that their hooks played much of a role in their college admissions process.

Adam Hirschhorn ’16, who will be attending Harvard College in the fall, said that the process was not any less stressful for him even though his brother and father both attended the school.

“I think the only effect of my being a legacy was that I knew more about the school, and thus that it was my first choice, but it didn’t relieve me of any stress or pressure,” Hirschhorn said.

In Harvard-Westlake’s college matriculation binders, students are anonymously listed by the schools they applied to, showing their GPA, test scores and whether or not they were accepted. There is an asterisk by the names of students who were accepted and hooked at the school they went to.

In the past five years, only 43 students with below a 4.0 GPA matriculated to Ivy League universities or other schools in the U.S. News and World Report’s top 10, according to the binders.

Graham thinks those outliers could be attributed to students not being honest about the amount of donations to the university that their family made. Alternatively, it could also be due to a hook that is not accounted for by the binder, such as a passion for or notable success in a particular academic field.

Additionally, at some colleges, the underrepresented group hook may expand to include genders, the Washington Post reported in March.

Some schools, such as Boston University, have a student body of 60 percent female, according to U.S. News and World Report, and may want to accept more males to future classes to equalize their ratios.

The admissions rate for MIT, for example, is significantly higher for women—13 percent compared to 6 percent for men— while schools such as Vassar College and Pomona College have higher rates for men.

Carmen Levine ’17 said that she would not be deterred from applying to a university even if she thought she had less of a chance at getting accepted than a male in her class.

“If that’s the only thing about a school that would detract me, I don’t think it would stop me from [applying] to the school,” Levine said. “I think as someone who advocates for gender equality, I would prefer to go to a school that’s 50/50.”

Levine said she also might consider herself hooked at some schools because she is a female interested in pursuing computer science.

Even though this is not a traditional hook, Levine thinks that perhaps the low number of women entering this field could work in her favor.

When choosing a college major, 0.4 percent of females select computer science, according to a report by the nonprofit organization Girls Who Code.

“I think that definitely some schools that have a greater male student body are definitely looking [for more female STEM majors], especially in the light of more awareness toward sexism in the STEM field,” Levine said. “But I think that’s true of every hook. As more awareness exists for the lack of minorities at schools, the lack of gender balance at schools and the lack of just diversity in general, then the awareness for hooks increases as well.”