Here’s a thought: in a place where we have the most cutting edge technology at our fingertips, where you can perfectly format an MLA-style paper with a tap, where our pages correct our spelling, where we can save what we write, where we can delete text–why would anyone still pick up a cumbersome, loud, complicated, clunky typewriter?

In the 1800s, if you wanted to write something, you basically had to write it. It seemed a miracle when by the latter part of the century, the first typewriters had emerged, like the 1870s Sholes and Glidden, which typed only capital letters and was dolled up like a period sewing machine, with flowers to boot. For the first time, the recording of human thoughts wasn’t limited by the speed of a pen on paper.

But what was cutting edge at that one moment was quickly outmoded (as we are accustomed to today) with newer, quieter models emerging every year, getting progressively sleeker and more efficient until another type of keyboard emerged: a keyboard that was hooked up to a computer.

What used to draw people to typing on a typewriter was that it was cutting edge, faster than writing, exciting, and simply easier. But with an even further evolution in the way we word process, the word processor, typewriters quickly lost their ability to stay cutting edge–or even relevant in the mainstream.

So why, I ask again, do you think people still use them?

Back then, products weren’t built to (for lack of a better word) crap out after three or four years of use. They were just built to, well, last. When you type on a typewriter, that purpose, that resilience, and that capability is felt in every key press.

Nothing quite feels like physically punching the keys of a mechanical typewriter. And I do honestly mean punching–there is nothing more satisfying than slamming each key into the paper, leaving a tangible, physical mark, and not just having a character emerge behind a cursor on a display.

As students, we type. A lot. So much so, that we can often fail to even absorb what we’ve written down. In the world we live in, we value rapidity for its own sake. And at times, this can lead to forgetfulness.

You cannot delete on a typewriter. Certainly, you can backspace over a word and dash it out, but then you have to start over. Instead of mindlessly transcribing, when using a typewriter, one must entirely intend to say what they are saying.

For my entire life, I’ve felt a longing for a time I’ve never experienced. In fact, I’d call it nostalgia. I almost feel as though I misuse the term, seeing as one can’t be nostalgic for something they’ve never lived.

Yet, here I am.

And I suppose that this is the root of my fascination, my curiosity, my simple attraction to the machines of yesterday.

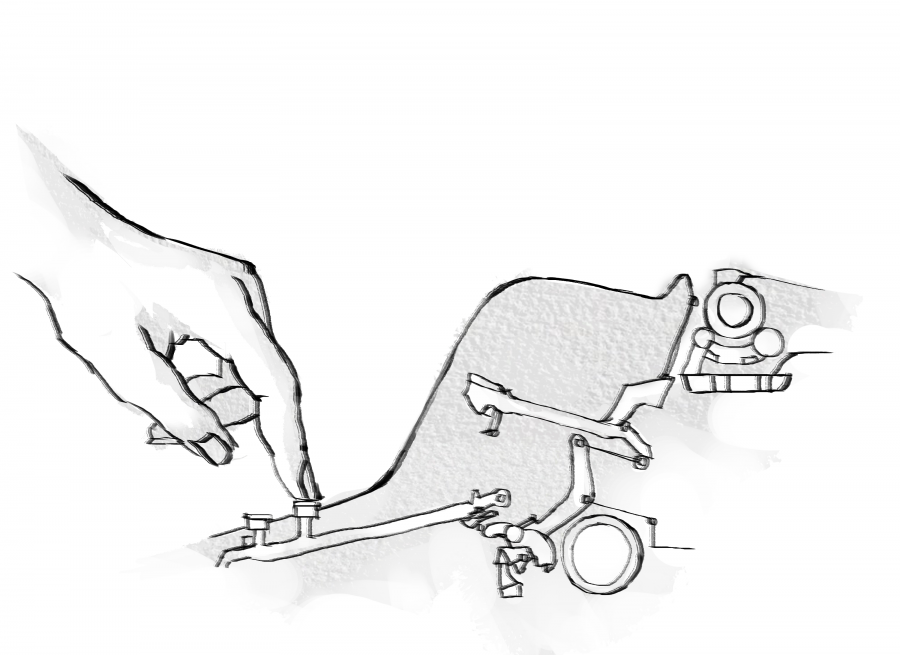

Having come across a number of these devices, and having had the opportunity to repair my fair share of them, my personal favorite is my 1948 Remington.

It strikes a distinct balance between two periods of time, almost symbolic of the end of the second world war, and just before the frenzy that was 1960s Madison Avenue.

There’s just nothing quite like getting your work done by clacking away at the elegant mechanical machinery beneath your fingertips, or the satisfying ding when you get to the end of a line, or the faint and pleasant old-book type smell of the ribbon as it winds like clockwork across its spools. Interacting with a typewriter is like no other typing experience because of just that: nothing else on a desk will truly interact with you at all. Siri might answer your questions, but I don’t think you’ll feel her guiding your fingers.

And this is why a person in today’s world who adores the technology and the future of tomorrow, who carries a Surface and a Macbook every day, will still, when the mood strikes, click a piece of paper into their Remington, their Smith Corona, their Royal, and get to work.