The administration and the IT department updated the iHW app on Aug. 18, adding an automatic check-in and check-out feature that tracks whether or not students are present on campus. After receiving multiple iHW notifications asking them to enable location tracking, upperclassmen raised concerns about the app and the potential privacy issues it posed.

Head of Communications and Strategic Initiatives Ari Engelberg said the tracking feature allows students, faculty and staff to check in and out of campus automatically, expediting the attendance system. He said that the iHW app does not track users’ specific locations; it only knows if students are within the “geofences,” or virtual geographic boundaries, constructed around the perimeter of the school.

Tracking while off-campus

“I think there’s a bit of a misunderstanding about what the iHW app is really doing,” Engelberg said. “If you’re on campus, [the app] doesn’t actually keep track of where on campus you are. And, it certainly doesn’t keep track of where you are when you’re not on campus at all. So, if you are running iHW, and you are in Santa Monica, the system will know that you are off campus, but that’s it.”

Engelberg said the location information gathered by the app, though limited, may prove useful during the pandemic.

“We decided to expand the functionality to all students to help with contact tracing in the era of COVID-19,” Engelberg said. “Knowing when someone came onto campus and left campus is helpful if there is a need to trace contacts in the event of a positive case of COVID-19 on campus.”

Student experiences with tracking

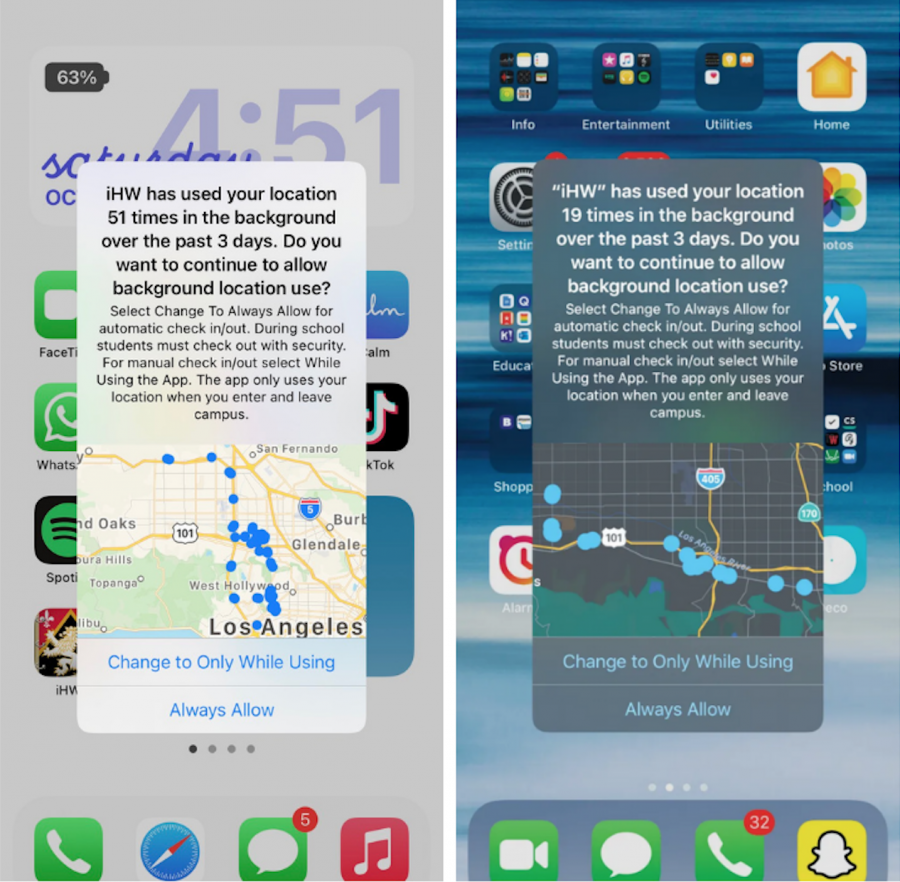

However, in a Chronicle survey sent to upper school students, 102 out of 138 respondents said the app has requested them for their location data. Joy Ho ’21 began receiving notifications from iHW at the beginning of the school year and said she believed the app was asking her to disclose her precise location.

“When I first started receiving the [notifications], they said that they were tracking my location continuously,” Ho said. “It showed me a map that had dots on it with where I’ve been, so I was worried. Every time I tried turning off [the app], it would keep telling me that it needs my location to check me in.”

Jake Futterman ’21 also received the notifications and said he is wary about privacy issues.

“In terms of the data being collected, I think I can trust Harvard-Westlake enough that it’s not being used for anything that I wouldn’t want it to be used for,” Futterman said. “At the same time, it’s not a school device, so I don’t necessarily want them, or anyone, to be tracking my location at all times.”

Software Development Manager Alan Homan explains tracking

Software Development Manager Alan Homan clarified that in order for the “geofencing” system to work, iHW needs to access users’ specific locations. When students turn on the check-in feature, the app uses their coordinates to determine whether they are within the school’s “geofences” and will subsequently record their attendance. Though iHW uses students’ locations, he said the administration does not look at the coordinates.

“[The app] may [identify your specific location], technically, but our app doesn’t subscribe to that and only gets activated when the boundaries are crossed,” Homan said. “If you were out on a Friday night and hit the check-out button, nothing would happen. We wouldn’t do anything with [the specific location data that the app collected].”

Mathematics teacher and Robotics Coach Andrew Theiss said that the “geofencing” system definitively requires that users give up their location data to iHW. He said the controversy surrounding iHW reflects the larger conflict between security and privacy, initially brought to national attention after the Sept. 11 attacks.

“At some point, your location goes through [iHW’s] system, absolutely,” Theiss said. “There’s this constant trade-off in society where if you compromise more of your data, you can have more features available to you. And there’s always a justification on either side of, ‘Oh, this is for your safety.’ In a case like this, it’s really easy to blindfold ourselves to the fact that we’re almost very easily going to open ourselves up to less privacy. This is [similar to] what happened with the Patriot Act, where after 9/11, people were willing to give up a lot of [their privacy].”

Like Ho, other upper school students, including Rohan Madhogarhia ’22 and Allegra Drago ’22, said they have received tracking notifications from iHW, accompanied by a map with their location pins.

Homan said the map is generated by the device itself; a new iPhone iOS update mandates that apps disclose whether they are receiving location data from students’ phones, even if they are not storing it. He said the iHW app technically began using users’ location data when the manual version of the check-in and check-out feature was first implemented Jan. 21; however, students did not know at the time because the iOS system was not released.

Students experience glitches when using app

Futterman said he set his device’s location settings to only enable location tracking while the app is in use. However, a glitch causes iHW to repeatedly ask students to switch their settings to “Always,” he said.

“If you don’t set it to ‘always allow location tracking,’ the app comes up with this error message telling me to turn on [the ‘always allow’ feature],” Futterman said. “I literally have to press ‘cancel’ twenty times [before the error notification disappears], and I can access my schedule.”

Homan said that if students switch the “Automatic Check In/Out” setting within the app, and not in the settings on their general devices, this issue should be alleviated.

iHW developer Jonathan Damico ’19 said that when he was coding and maintaining the iHW app as an upper school student, it was not designed to have a check-in or check-out option. Though he said he understands the administration’s point of view, he offered a potential solution that would mitigate any privacy issues.

“[Instead of asking for students’ locations, the administration] can check to see if you can if you’re on Harvard-Westlake WiFi, because if you’re [using their] WiFi, then you’re on campus,” Damico said. “I’m sure [the check-in and check-out feature] is a positive thing. But it’s easy to see how this could be abused by an institution, right? At the end of the day, if the [administration had] sent the student body [a message that] we’re gonna [allow the app to receive tracking location, and] it’s for these reasons, I’m sure people would be on board with it.”