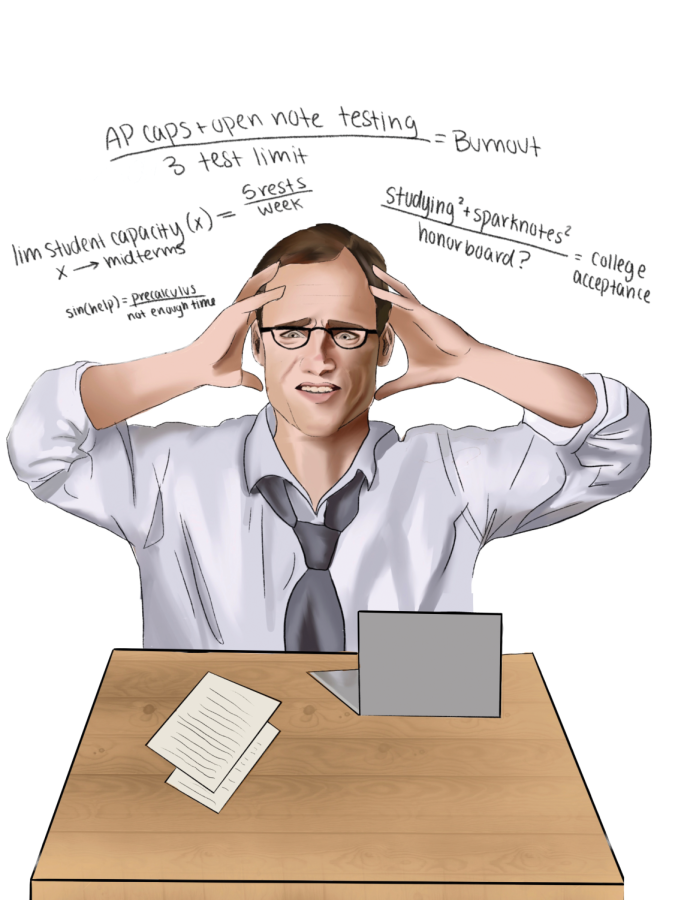

Under(standing) Pressure

President Rick Commons looks for ways to manage student mental health and academic difficulty.

November 16, 2022

As students poured into the science office before finals, worrying about their upcoming exams, Science Teacher Yanni Vourgourakis ’90 thought about the evolution of academic difficulty at the school. Despite the stress and anxiety buzzing in the atmosphere, Vourgourakis said he couldn’t help but notice the differences from his time at the school as a student.

Vourgourakis said students at the Harvard School for Boys were less preoccupied with the stress they faced while still wanting to succeed, and the increased focus on stress nowadays causes more anxiety.

“It’s always been a place where people wanted to do well, and they expected a lot of themselves, but I don’t think we ever felt like we were competing against each other,” Vourgourakis said. “It wasn’t socially acceptable to not do well, but we didn’t seem quite as neurotic about it as [students now]. I don’t think we were so aware of stress, because no one talked about it. Now, there’s so much awareness of it because it’s all anyone ever talks about. It’s kind of self-perpetuating in some ways. There is clearly an objective amount of stress around here, but there’s so much focus on it and trying to alleviate it, which can’t be done, that it’s making everybody kind of crazy.

Vourgourakis said he feels that the difficulty of academics has decreased significantly since his time at the school both as a student and young teacher, when students had to take responsibility for their work and the way teachers treated them.

“Pressure was much higher,” Vourgourakis said. “There were no homework policies or things like that. You just got what you got, and you worked pretty hard at times, but it never occurred to us that we had any right to complain about it.”

Vourgourakis said he believes students have a different idea of authority than they did back then.

“When parents ask me, ‘what’s the biggest difference between now and then,’ I’ll say ‘the difference is that back then, it was our fault,’” Vourgourakis said. “Honestly, if a teacher was really mean to you, or did something that was way out of line, you never thought that there was any recourse. You just kind of got on with your life. You talked your trash behind their back and moved on with it. There was a different sense of where you stood in the world, and your generation seems to think that you’re already like adults and equals with everyone else around there, and I disagree.”

Vourgourakis said he is concerned about students’ mental health but is more preoccupied with the idea of students using mental illness as an excuse.

“I worry about [the popularity of discussing mental health] a little sometimes, but I think it’s a good thing for people who really do have these problems,” Vourgourakis said. “It’s a bad thing for people who use it as an excuse to not do their best effort. So it’s a good thing, because there are people who really do struggle with these things, and it’s good that they’re not stigmatized, but it’s a little bit concerning that it becomes an excuse, or a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Community members reflect on the school’s rigor

Ellie Whang ’24 is a teen hotline responder for Teen Line and a Peer Support Trainee. Whang said while she has observed that the stress from schoolwork and homework is overwhelming for students, it is not the sole contributor to mental health struggles for most students.

“Since we have such a competitive environment around school, on top of the stress that people might have with managing their schoolwork, that competitive nature of our school in particular can increase a lot of anxiety that people have to perform well,” Whang said. “I wouldn’t say that school is the main cause, but it can definitely amplify any feelings that people have.”

Whang said she had a teacher who was not accommodating of her personal mental health problems, which ultimately affected her performance in class.

“I had a teacher who wasn’t as understanding because, from her perspective, and I completely understand this, everybody was struggling returning from the pandemic,” Whang said. “So obviously everyone was going to have some issues, which is true, but the thing that I was going through was a little different than mental health being affected just by the pandemic. Then she ended up understanding towards the end of our time together at the end of the school year, but regardless, not having that kind of support did suck a little bit, but I think that’s just because I didn’t take the time to really explain to her either what was really going on, which I feel like would have been more effective.”

Whang said her Peer Support group provides a beneficial outlet where students understand the unique pressures and workload at the school and how they affect mental health.

“Since at Peer Support we all go to the same school, we understand at the same level the amount of stress that we all have, as opposed to if you talk to someone from another school, they won’t get it as much,” Whang said. “I do feel like talking about school stress and how it affects mental health is a very present topic in Peer Support, just because everyone kind of has that same understanding of how much pressure some people can put themselves under.”

Whang said the kindness teachers showed during the pandemic led to a hard readjustment to regular, non-pandemic workload and more anxiety.

“I definitely feel like the leniency that teachers gave was helpful at the time, but now since we’re recovering from that and coming back from that, it can be harder for students to readjust to the normal rigor that Harvard-Westlake is used to giving out,” Whang said. “So I think that’s an issue that some people are having right now, but I think the school has a lot of great resources that help students manage this kind of stress coming back from the pandemic.”

Teachers discuss their viewpoints of mental health at the school

Like Whang, History Teacher Lilas Lane said that the pandemic had an effect on everyone’s mental health and work level.

“COVID has had an effect on the rigor because there [were] a lot of [kids] freaking out, [so we asked] can you hold people to a high [standard] when they’re on Zoom?” Lane said. “Then [with] the mental health aspects of all of this, and kids hadn’t been exposed to anything like this, we had to figure out how [do] we test and teach effectively.”

Lane said she thinks the younger generation’s hyper-awareness of mental health issues from an early age may prevent students from seeing what serious mental health struggles actually are.

“I think the awareness that people have about mental health is not negative because it’s good to have awareness about mental health, but when you’re 12-13 years old, and you’ve been told all about anxiety, depression and these things that you don’t really have the intellectual capacity to understand, it becomes just like anything, when you’re a teenager, [a sole piece of your identity],’” Lane said. “Now you can go on to social media and hear all about anxiety. I’m not saying knowledge is bad, but sometimes knowledge is not appropriate for a certain age, and most of us feel anxiety but not most of us have [an] anxiety disorder. That’s extreme. It’s normal to feel anxiety in stressful situations. It’s not normal to have panic attacks. Most of us are not at that level of real mental illness, but now we’re all thinking about it so much.”

Lane said that as the school has become less rigorous, students have lost sight of the point of learning.

“I feel like that’s another big issue for your generation, and that’s the thing that I really worry about when it comes to rigor, because I don’t think rigor should be hard for hard’s sake,” Lane said. “I think rigor should be about being thoughtful and deep in the way that you think about things. It’s about critical thinking, and unfortunately, you have to get a certain base [of] knowledge before you can think critically. You have to be able to look at multiple sides and know things fairly deeply. This is why rigor matters.”

Lane said that she expects a high quality of work from students but understands their personal struggles and tries her best to support all students in individual ways.

“I am the advocate of caring, warmth and demanding high standards, so the way I feel about it as a teacher is sort of like how I have as a mother,” Lane said. “I love my students, and I want what’s best for them, but what I think is best for them is not making it easy for them, it’s challenging them to do their best work. I’m going to try to do what I can to support them so that they can kind of keep moving in that direction, but I believe it is not serving my students if I go easy on them, especially those students who don’t need that. The students who are falling apart—like we all go through things where our parents are getting a divorce, or somebody dies or we’re having a mental breakdown—I will support the hell out of those kids, and I will make concessions for those kids. But I’m not going to be like that for kids who just are procrastinators. I’m gonna try to push them to be better, to learn how to learn and be effective.”

According to a Chronicle poll, 98.7% of 158 students surveyed said they had felt anxious over schoolwork.

87.4% of students said the school is not lenient enough regarding schoolwork. 61% of students surveyed said they had not done an assignment before because they were struggling with mental health, and 63.9% of those students said a teacher of theirs had not been very understanding of their mental health struggles.

Psychology Teacher and School Counselor Michelle Bracken said mental health problems interfere with students’ abilities to do work, but she believes schoolwork is not the main contributing factor.

“For some people, particularly [with] anxiety, depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder or really anything, those things get in the way of your ability to process information, focus in class, do your homework and sit with your thoughts,” Bracken said. “It’s a lot of things that other people can do on their own. It just makes doing any kind of work harder, not less rigorous. So people don’t leave here because they’re like, ‘oh, I have a mental health problem and this is too hard.’ They leave here because of a mental health problem, and maybe I need something different, as opposed to easier.”

Faculty and students talk about their approaches to mental health

Cole Hall ’24 said he sees many students that feel pressure to stand out due to the competitive environment of the school.

“Everyone at Harvard-Westlake has the mindset that [they] got in for a specific reason or just because they’re extremely smart,” Hall said. “That can leave some students, at least from what I’ve heard, feeling like they aren’t as good as others in all aspects. They feel they have to stand out in one thing to be noticed because, in the grand scheme of things, Harvard-Westlake has such a diverse talent pool. It’s kind of hard to find something that isn’t already taken. That can leave a lot of students feeling kind of dejected and feeling like they have to put all their work into school.”

Hall said he continues activities that he enjoys and tries not to get caught up in leveraging his activities.

“I think I realized that everyone was trying to find [a niche] last year in my [Peer Support] group,” Hall said. “Once I realized that, I tried to have a balance and try as best as I could to enjoy the things I do. Ultimately, the goal is that, if I enjoy it, I’ll put more time into it and be better, but I definitely do find myself relapsing or thinking that way. Sometimes I think it’s impossible here not to.”

President Rick Commons said the school has been adapting to the changing social environment and increased mental health awareness by finding ways to preserve excellence in the school community.

“I do think the school’s been evolving as you’d expect a good school to do, and I’m sure the school has always evolved,” Commons said. “I think the evolution for us, which is not dissimilar from the evolution for other schools like us, has been one in which we wanted to maintain our distinctive commitment to multi-faceted excellence while ensuring that we are identifying ways in which students are not thriving emotionally as they pursue excellence and working to address that, and then identifying ways in which the pursuit of excellence is perhaps not available to all members of the community—which is a kind of vague way of saying we know that students who are at the top of the class academically and have an extracurricular activity in which they are excelling are more likely to feel good about their experience than students who may be struggling academically and may not have found the thing extracurricularly that makes them feel successful.”

Commons said educators are aware of the mental health struggles of teenagers, and the school aims to help students while maintaining its historical success and excellence.

“I don’t know another educator who is not aware that the mental and emotional health of adolescents, especially high-achieving adolescents, is much more of a concern than it used to be,” Commons said. “It’s fair to say that it has reached a crisis. I don’t know another educator at another school who’s saying ‘forget making the kids healthy, forget giving the kids an opportunity to enjoy their lives. We need to teach them how to think and nothing else matters.’ Nobody says that anymore, but change is hard and especially hard at successful institutions, and Harvard-Westlake has a long history of success. So for us to work at change inevitably brings questions about the extent we are risking the excellence DNA of our institution. That’s the trick that we are continuing to try to pull off and to not compromise the excellence and the opportunity to pursue excellence at this place while doing everything we can to make the experience more joyful and healthier.”