It is 8.00 a.m., and students are trudging to class, chugging their caffeinated drinks in the hopes it will keep them alert for the next 75 minutes. This scene is all too familiar, but it does not have to be the norm. The decision to start school at 8:00 a.m. turns students into malfunctioning, sleep-deprived zombies. Meanwhile, a growing number of medical studies — as well as an increasing number of schools and state legislatures nationwide — agree that it does not have to be like this. Other private schools in the area, including Campbell Hall, Crossroads, Oakwood and Marlborough, have all shifted their start times past 8:00 a.m. Bill No. 328, a new California law that took effect in 2022, requires that all public high schools start past 8:30 a.m. The Upper School stands as the odd one out — it is time to align with these changes and shift our own start time to 8:30 a.m.

Bill No. 328 was the first of its kind in the nation to implement a later start time for high school students, but other states are expected to follow. In 2023, Florida passed a law to be implemented in 2026 that sets the same floor. Legislators in at least nine other states, including New York, Texas and Nevada, are proposing similar changes. Our current 8:00 a.m. start time is neither universal nor set in stone, and we should change it if it promotes better outcomes for students.

Prevailing scientific evidence proves that starting school at 8:00 a.m. poses a legitimate threat to students’ health and well-being. For instance, 72.7% of high school students get less than eight hours of sleep each night, which is the medically recommended amount of sleep for adolescents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This deficit is especially pronounced at the Upper School, where students are put under more academic pressure and receive more homework than their counterparts nationwide. Many of my classmates often go to bed absurdly late — even after 1:30 a.m. For students who live far from school, some as far as Lancaster or Riverside, their situation is more severe. Several students wake up at 5:30 a.m. or earlier. This is brutal for adults, let alone teenagers, who require even more sleep.

These effects are real and serious. The CDC described the epidemic of sleep deprivation among high school students as a “substantial public health concern,” noting that a lack of sleep can lead to lower grades, mental health struggles and antisocial behavior. High school students themselves know that it just doesn’t feel right to be waking up at the crack of dawn for school.

It’s a biological truth that adolescents have delayed circadian rhythms that cause them to fall asleep and wake up later. Most teenagers can’t fall asleep before 11:30 p.m. and remain in “sleep mode” until 8:00 a.m., according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). That’s not something that can be fixed through encouraging students to “go to bed earlier.” The school should accommodate its students’ inherent biological clocks instead of working against them.

The American Psychological Association (APA) compiled a series of studies proving the benefits of later start times. Some of these benefits include improved attendance, higher GPAs and standardized test scores and fewer student car crashes. When the Seattle School District moved back its start times from 8:00 a.m. to 8:50 a.m. in 2016, students’ median sleep time increased from six hours and 50 minutes to seven hours and 34 minutes, according to a study in the journal Science Advances. Even a few extra minutes of sleep can be crucial for adolescents’ physical and mental health. Disruptions to their circadian rhythms, even minor ones, leave high schoolers feeling fatigued and drained, and this impedes their performance in the classroom. It’s imperative that we address the academic and social consequences of student sleep deprivation. With several states and local school districts beginning this change, it’s time for our school to do the same.

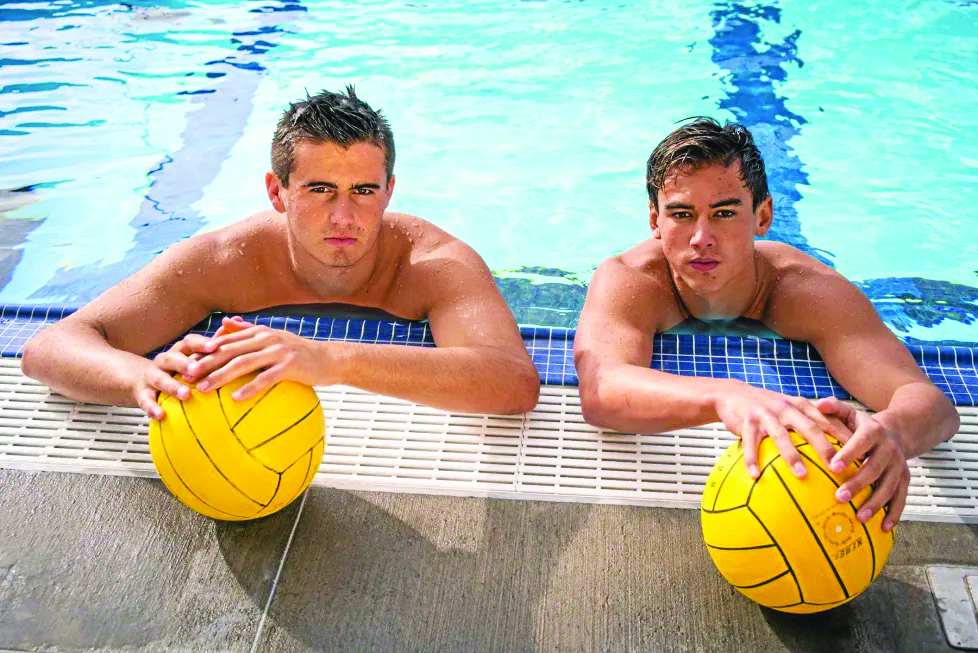

This shift would not inflict a drastic change in our school’s schedule either. Though school would have to end later to keep the block schedule intact, it is more important that we follow what the science says is best, and most medical organizations have agreed on 8:30 a.m. at the earliest. The bus schedule would also have to change, as would the start and end times for after-school sports. But these changes are a matter of willI — if other schools can do it, so can we.