Math teacher Kevin Weis was 12 years old when he realized he didn’t believe in God.

He had stopped attending Sunday school church lessons several years before, but now he was ready to fully commit to atheism. He told his parents that he would no longer attend any church functions.

Weis said he changed his mind about religion largely because of his seventh-grade science class, where he learned about evolution.

“People who are afraid that teaching kids evolution will make them atheists have a valid point,” Weis said.

In the past few years, increasing numbers of people have been converting to atheism.

An April report by the Pew Research Center predicted the percentage of atheists in the United States will increase from 16 percent in 2010 to 26 percent by 2050.

Statistics released this year by Harvard University show that 23.3 percent of freshman undergraduates are agnostic and 16.6 percent are atheist, while only 17 percent are Catholic and 17 percent are Protestant.

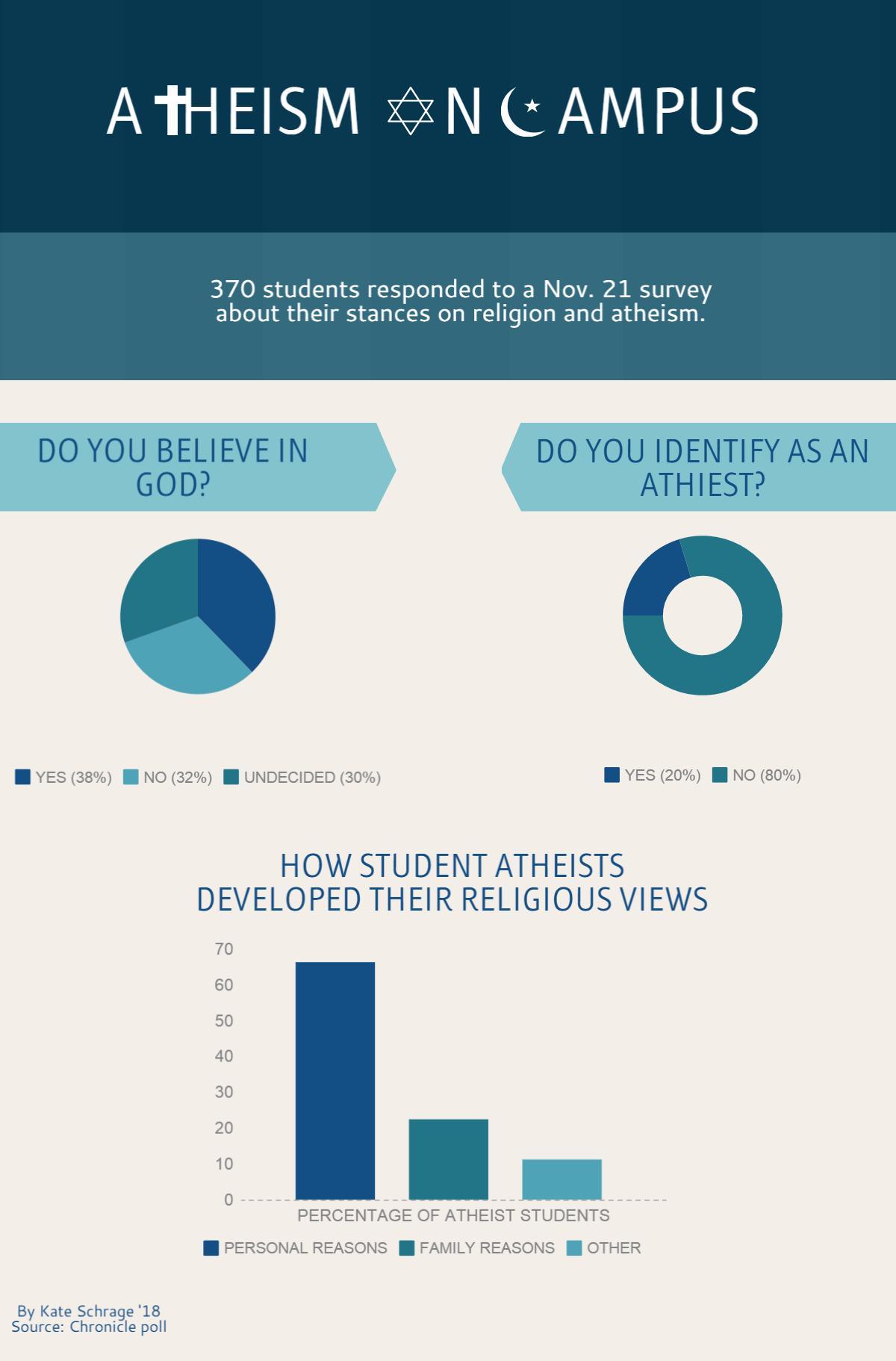

In a Nov. 22 Chronicle poll, 32 percent of 370 students said they do not believe in God, 38 percent do, and 30 percent are undecided.

Weis, a self-described “militant atheist,” said he tries to encourage others to become atheist and is now open about his beliefs.

“I took a year off after high school, and I took a community college class before I went to college,” he said. “I was kind of bored, so I took a class on the philosophy of religion, and the professor of that class was a Christian minister and obviously had very religious views. Our final paper had to be on our own views of religion, and I titled my paper ‘Anti-theism.’ Not ‘Atheism,’ but ‘Anti-theism.’ He took umbrage to that and ended up failing me. That was a rough time.”

However, Weis feared sharing his religious views when he started teaching at Harvard-Westlake over a decade ago, he said.

“I don’t know where it clicked that I just decided that I should be able to be open about my beliefs about this, but one day I just did, and I haven’t looked back,” Weis said.

He does not dislike religion or others’ belief in God, but he disapproves of the religious mode of thought, he said.

“I’m against the general approach of gaining knowledge through faith,” he said. “I do not think faith is a viable way of gaining knowledge about the world. There are good ways of gaining knowledge about the world, there are better ways, and it’s a spectrum. The way religious people gain knowledge about the world is not a viable way, and I’m against that process.”

One advantage of religion is the community that forms around it, Weis said, but he finds a sense of community in atheist organizations and frequently visits atheist blogs and websites to keep up with news.

Robert Heckerman ’17 also identifies as an atheist.

“I believe there’s no God, and there’s no spirituality in anything,” Heckerman said. “It’s just simple science.”

However, unlike Weis, Heckerman was raised in a primarily nonreligious family, which influenced his religious views heavily, he said.

“It mostly comes from my brother (Jonathan ’15) and my dad,” Heckerman said. “They’re both super atheist too.”

Heckerman’s knowledge of science reinforces his belief that God does not exist, he said.

“I guess it’s just through learning about science and evolution and all the stuff that kind of disproves the claims of religion,” he said.

He feels that most people are accepting of his views, including his mother, who is “more of a spiritual person,” he said.

Heckerman said he has no regrets about not being a member of a religious community.

“I don’t see the point of having a community around what I think is false,” he said.

Other students identify as agnostics, people who neither believe nor disbelieve in God. Paul Anderson ’16, an agnostic, said he hasn’t taken a definitive stance on the existence of God because he feels no evidence exists for or against it.

“You could say there’s really no way to prove there’s a god, but there’s no way to prove there isn’t,” Anderson said. “As time went on, I basically settled on the fact that there’s really no way to know, so why bother?”

However, Anderson said he believes in evolution and generally follows a scientific mode of thought.

“There’s really no way to believe in creationism if you look at the evidence and draw a conclusion from that, versus starting with a conclusion and cherry-picking evidence to suit it,” Anderson said.

Zach Belateche ’16, also agnostic, believes in evolution and the Big Bang, the prevailing scientific theory of the universe’s origin, but he has no way of knowing if these scientific phenomena were caused by God, he said.

“I think it’s totally possible that the Big Bang could have been created by some supreme being,” Belateche said. “We don’t know. But I don’t believe that God created the world 5,000 years ago, because that’s pretty much been disproven.”

Belateche said his mother is Christian and his father is nonreligious, so he has always felt free to develop his own religious identity and eventually came to the conclusion that no empirical evidence exists to confirm or deny the existence of God.

However, Belateche tries to avoid discussing religion with others when possible in order to not offend anyone, he said.

“I don’t really vocalize my opinions,” he said. “If there’s a conversation about religion, I just say, ‘I don’t know,’ and shut up. I personally try to be accepting of people’s views unless they use religion to be bigoted, like to oppose gay marriage or oppose abortion. Then I have a problem with that.”

Dan Barker, co-president of the Freedom from Religion Foundation, said that he believes far more people under the age of 20 are atheists than some might suspect, and increasing amounts of atheists are willing to admit to their often controversial religious views.

Barker said that these younger atheists are often underrepresented in politics because many do not vote.

“If the twenty-somethings would show up, the whole country would sit up and go, ‘Whoa,’” Barker said.

The Freedom from Religion Foundation aims to create a national community for atheists by holding conventions and sponsoring essay competitions.

Barker has written several books about atheism, participated in debates on the existence of God and appeared on television shows including “The Daily Show” and “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

Now a prominent voice in the atheist community, Barker wasn’t always an atheist.

For 19 years he was a Christian minister. He lived in a Christian family and wrote songs with Christian themes for which he still receives royalties.

“When you’re raised like that, it kind of latches onto your brain,” Barker said. “Like, ‘the Bible is the source of all truth.’ I thought I knew the truth. Everybody does. There’s something about human nature where everybody thinks they’re right.”

Barker said he began doubting Christianity when he considered the existence of Adam and Eve.

Many preachers deny that Adam and Eve were real people and consider their story only a parable, especially due to scientific knowledge that has emerged in the past few hundred years, Barker said.

However, if one of the Bible’s most fundamental stories could be false, he wondered if other stories are false as well.

“When you learn more about science and you learn more about evolution, you know there couldn’t have been an Adam and Eve,” Barker said. “What other characters are made up? Maybe Yahweh, maybe God is.”

Barker said he did not immediately become an atheist, but over time his doubts grew, and he slowly came to the realization that he did not believe in God.

“I was all by myself,” Barker said. “It was kind of scary. And I actually kind of humbled myself. After years of thinking I was right and God spoke to me and everybody else was wrong, I had to come down from that pedestal.”

Barker said he also began to question the morals expressed in the Bible and the goodness of the god it portrays.

“It has a lot of immorality,” Barker said. “[God] is just cruel, bloodthirsty. The only way he can be appeased is with bloodshed.”

Barker connects with other atheists through the internet and the Freedom from Religion Foundation.

“[Church] is kind of like a watering hole,” Barker said. “It’s a good place to find a mate. Churches have been that way historically. Now the watering hole is the internet.”

Barker also said that the atheist community treats its members with more equality than churches, which have a strict hierarchy of church officials and clergy members.

“Most churches are top-down,” Barker said. “But atheists are bottom-up. It’s a great community where everyone’s equal. It’s actually a better community because it’s voluntary, whereas in a lot of Catholic communities you feel like you have to. There are lots of kids who are forced to go to church and hate it.”

Since his transition from Christianity, Barker has faced harsh criticisms from religious people familiar with his story, he said.

“The majority of religious people, their faith is based in a book called the Bible that insults non-believers,” Barker said. “In fact, all non-believers and pagans have to be put to death in the Bible. Every Christian handles that differently. You’ll find some wonderful, loving Christians, and you’ll find the hateful ones, the ugly ones, the intolerant ones.”

Christian Club member Nathan Lee ’16 said that he feels questioning religion is healthy, and for people who believe in God, thinking analytically about religion reinforces their beliefs.

“It’s healthy to be doubted,” Lee said. “So it’s not something like my parents say this, my church leaders say this, so it has to be true. It’s not something that’s said, it’s something that I’m constantly trying to evaluate.”

Lee said that many people assume science and religion are incompatible, but he believes they should complement one another.

“To me, I think there has to be a way to have science support religion,” Lee said. “If you say, ‘We have to do it this way,’ and science either works or doesn’t work, that’s something that’s pretty dangerous, but it’s like you’re rejecting fact. But if you’re able to say, ‘Science informs my own religion or my own beliefs,’ that’s something that can be good.”

Jewish Student Union leader Jona Yadidi ’16 said she also believes that science and religion can work in unison. For example, she believes that God may have caused the Big Bang.

For Yadidi, Judaism offers not only a spiritual belief, but also a community and cultural identity, she said.

“I love that every Friday night my family gets together and has Shabbat dinner with each other,” Yadidi said. “It’s a highlight of my week that I always look forward to.”

For atheists like Weis, forming a community around religious views is far more difficult.

However, Weis is a member of several atheist organizations, including the Brights, a group that refers to atheists as “brights” because atheism has a negative connotation.

Weis said he has not decided yet if he agrees with the Brights’ goal, but he is glad to be a member of an atheist community.

“I’m not atheist,” he said. “I’m bright.”