Waiting in that ventilated hall of the third floor of Seaver is what I remember most, or best, about my Honor Board experience. Most of the specifics about the actual hearing have faded in the subsequent two years, but that cool draft sending a faint shiver straight down my spine as I loitered outside the door, preparing to give my testimony, lingers in my memory.

I sat cross-legged on the off-white marble floor of third floor Seaver, tugging on the shoulder of my royal blue cable-knit sweater. My mom had suggested it this morning â “itâs a nice color,” she told me. “You shouldnât look like a slob today.” It fit too snug around my shoulders, but I wore it anyway.

My dean stood a few feet away. It was the beginning of October of my sophomore year, and I barely knew her. She tried her best to engage me in small talk.

“So,” she said with an audible sigh, “who are your friends?”

I rattled off a few names.

“Oh.”

I returned to the sweater-tugging.

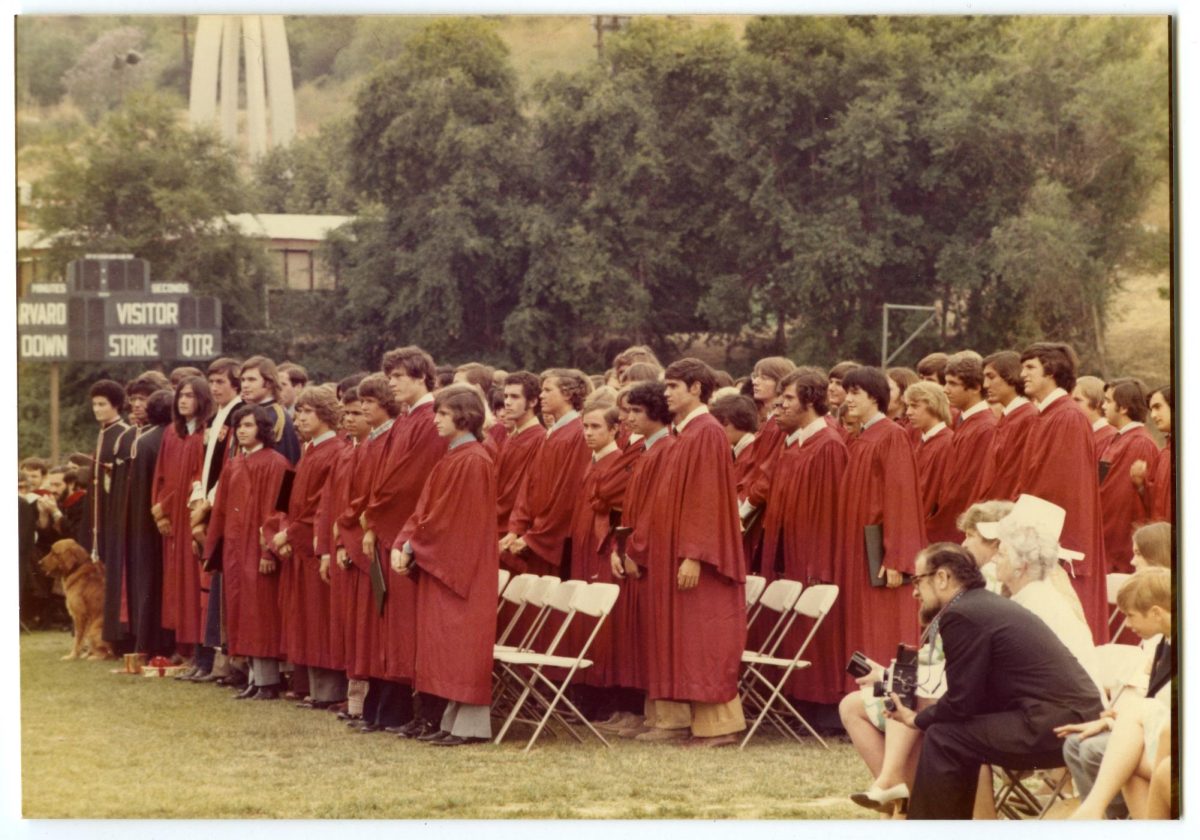

Head of Upper School Harry Salamandra had pulled me out of English on Friday of the prior week and laid his accusation on the table. I fessed up without hesitation. He told me what would happen next: the Honor Board, comprised of the Prefect Council and faculty members, would be presented with the facts of my infraction and decide, as a formality, whether or not I had officially violated the Honor Code (which I knowingly had done, so I wasnât exactly expecting them to disagree). A hearing would then be scheduled where the teacher and I would be questioned by the Board, with a notification of my punishment to follow in a few days.

In the interim, he told me, I should write a statement detailing the facts of the situation for the Board to look over prior to the hearing â why I did what I did and how I feel about it in hindsight. Salamandra dropped me off outside of my class, but I didnât go in. I rushed to the bathroom and locked a stall and cried, not because I was in trouble or because I had to tell my parents, but at the thought of facing judgment from a jury of my peers. I knew them. I voted for them. They were my age, and they would be deciding my fate. Was my case the yearâs first? Was I that single screw-up?

I wrote my statement that night. I was and remain immensely contrite about my actions (though at the time I was more sorry that I got caught; true remorse and shame came with maturity and perspective), but I recounted my side of the story without emotion â I just ran through the facts, the timeline, the nitty gritty.

A day or two after turning in my statement, my hearing was scheduled for after school in a Seaver classroom.

The door swung open and my teacher walked out, carrying a large folder stuffed with papers. I wasnât aware that she had been called in first.

“Good luck in there,” she said. I could tell that she meant it.

Head Prefect Sammy McGowan called me in without looking me in the eye. My dean followed. Honor Code violators are accompanied by their deans in the hearing to serve as advocates or to provide broader viewpoints about the wrongdoerâs work ethic or personality. Since I had spoken to my dean on only three occasions, I figured she was there for moral support.

Four faculty members and eight prefects seated at desks assembled in a circle introduced themselves. A sophomore representative, a childhood friend, said “Hi,” without lifting his head from his notes.

The preliminary questions were easy enough â I just corroborated what I had written in my statement. I said that I understood the harm my action had caused. Father J. Young looked concerned.

“Do you understand how this violates the entire community, not just your teacher and the class?”

“You mean, my teacher wonât trust any of her students anymore because of me. Is that what you mean?”

He asked if I understood how it affected the whole community.

I had no clue what he meant. How did this have to do with anyone beyond my teacher and immediate peers?

The hearing ended after only 10 minutes of grilling.

I stopped by my deanâs office a few days later to face my punishment. I read the statement, which said that I seemed embarrassed and that I understood the impact of my actions on a small scale, but that I was too compliant, that I went along with everything they said. Was I supposed to argue with them, to stand up for myself? I simply agreed with their assessment of the infraction. Why was that a problem?

The Honor Board had recommended, among other tasks, to “re-integrate me into the community,” a one-day in-house suspension, which would ruin my record. College and future happiness had slipped away.

But on a page stapled to the Honor Boardâs recommendation, the administration disagreed with the Boardâs penalty. No suspension.

Instead, I would come in on a Saturday afternoon and write a research paper about famous cases of plagiarism.

That the administration mitigated my punishment didnât alleviate my guilt or make the experience easier or less terrifying in retrospect. The teacher who brought the case against me worked hard to make me feel comfortable for the rest of the year. Life, as I knew it, went on without a hitch.

Itâs only now, with two years of space, that I can reflect on the impact of facing the Board. My record isnât tainted and my college changes arenât impeded, but that cold hallway and the draft against my skin is a memory that doesnât fade.

Authorâs name withheld by request