Keeping the Olympic flame alive

August 26, 2021

My heart pounded as I rubbed chalk onto my hands, hoping I would remember the intricate sequence of skills that comprised my uneven bars routine. I rehearsed it mentally for weeks, a welcome distraction from fourth grade classes. But despite my experience with competitions, stress clouded the excitement of sticking my landing. This setback led me to quit gymnastics, but the sport remained an important part of my life. Why? It goes back to the first Olympics I can remember: London 2012. Ever since I watched gold medalists Gabby Douglas and McKayla Maroney soar through the air, the Olympics, and particularly gymnastics, captivated me.

Although I love the Games, there is clearly a systemic issue with gymnastics and the Olympics themselves. In 2017, Judge Rosemary Aquilina sentenced former U.S. women’s gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar to 175 years in prison for sexually abusing hundreds of young women. The following year, USA Gymnastics closed a U.S. Olympic training camp owned by coaches Bela Karolyi and Martha Karolyi; the ranch allegedly incited physical and psychological maltreatment and exposed athletes to Nassar’s abuse, according to the Washington Post. U.S. gymnast and Olympic gold medalist Aly Raisman sued USA Gymnastics and the U.S. Olympic Committee, claiming they were aware of Nassar’s abuse and failed to act. A victim of Nassar’s abuse, Raisman said USA Gymnastics is “rotten from the inside out.” Sexual abuse within gymnastics has a decades-long history. But the Olympics, the pinnacle of elite gymnastics, have only intensified this issue, allowing abuse to occur on the sport’s most influential platform.

The 2021 Tokyo Olympic Games spotlighted additional issues caused by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and other U.S. athletic associations. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency prohibited track runner Sha’Carri Richardson from competing after she tested positive for marijuana consumption following her mother’s death. Conversely, in a misogynistic and morally incorrect twist, the IOC allowed fencer Alan Hadzic, who has three rape allegations, to compete. The IOC also banned swim caps for natural Black hair and Black Lives Matter apparel during anthems. And above all, COVID-19 cases in Tokyo reached a record high while the Games were taking place.

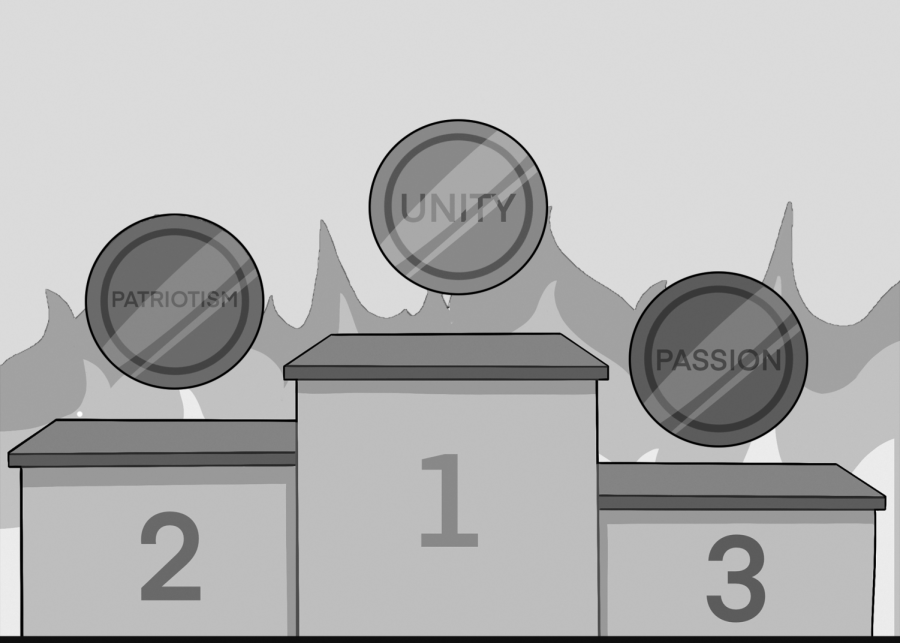

These problems are urgent. But after a year of separation and loss, can we afford to lose the camaraderie of the Olympics when we need it most? We should be critical of the parts of the Olympics that are inequitable, and, when necessary, of the institution as a whole. It is impossible to deny there is much work to be done, legal action to be taken and voices to be heard. There is a need, however, for the Olympics, especially after the isolation caused by COVID-19. We need the togetherness and joy that come with the Games. Athletes need to see their years of work pay off, and we need the pride and patriotism of cheering them on. We need the chance to shift focus from our everyday lives and consider what it means to operate as a country and a world. We must remember that at the core of the Olympics are the Olympians themselves.

The Olympics both divert our attention from our lives and teach us about life. They inspire us to be perseverant but also to take care of ourselves, as Simone Biles exemplified by stepping down from the individual gymnastics finals. It is crucial that we remember these international representatives are humans who grapple with obstacles ranging from trauma to tendonitis.

The Olympics are a microcosm for our global community: flawed, dynamic, diverse and human. They are possibly the only thing we truly have left in common and the last platform we have to coalesce. Although I gave up on gymnastics myself, the Olympics allow the sport to remain a treasured piece of my life. We can’t give up on the Games, for the sake of all the people like me who cherish watching them, for the athletes and for the international unity the Games encourage.