Misrepresentation in Media

Students and faculty weigh in on diversity in media and contemplate how pressure for “progressive” writing may lead to inauthentic representation.

October 13, 2021

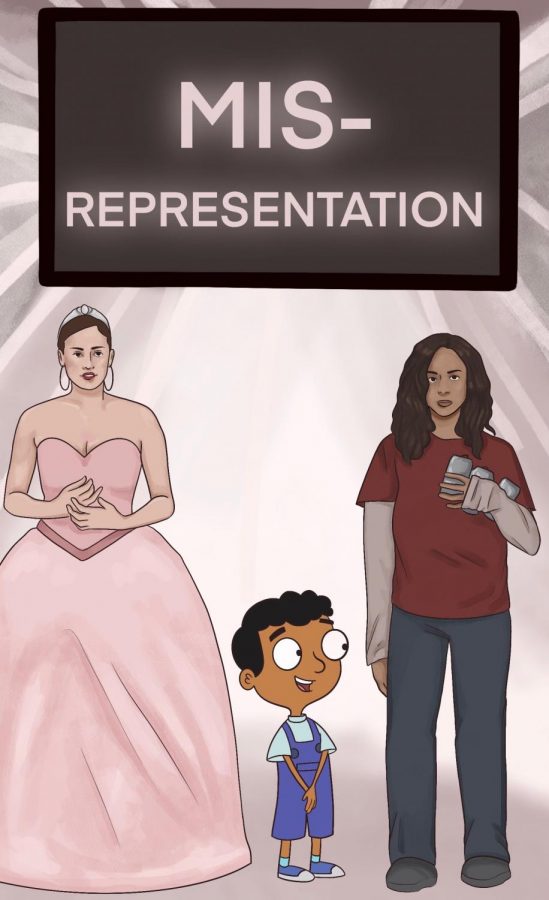

Fernanda Herrera ’23 flipped through the channels on her television, wondering why she did not look like any of the characters on screen. Could she ever be like the princesses and superheroes in her favorite movies? Or was that a possibility only afforded to her caucasian friends? Growing up, Herrera said she felt alienated by this lack of representation and was resentful of her own ancestry.

Herrera said her main issue with the lack of diversity in media is that the people of color portrayed are represented inaccurately or negatively.

“There were never, and still aren’t, very many TV shows with Hispanic characters,” Herrera said. “A lot of the Hispanic characters that did show up were token characters who were either really Americanized or whose only traits were speaking Spanish and eating tacos.”

Herrera said the only representation she could find as a child was harmful or stereotypical, since the shows she watched amplified common misconceptions and racial tropes as a form of comedy. She said Olivia, a Hispanic girl from the teen drama “On My Block,” feels like an offensive and unsuccessful attempt at representation.

“In ‘On My Block,’ [Olivia] spoke Spanish with an American accent, which makes no sense because she was born to immigrant Mexican parents,” Herrera said. “Ronni Hawk, the actress, is non-Latine white and has played Latina characters on other shows as well. Can’t they find any Hispanic actresses? I thought that if [my culture] wasn’t showing up on the big screen, then there must be something wrong for people to not demonstrate it.”

Shanti Hinkin ’22 said the lack of minority representation in the media is worsened by insensitive racial tropes and stereotypes. She said the inaccurate portrayals of these groups also appear in some children’s shows. Hinkin said Baljeet from the children’s show “Phineas and Ferb,” who is characterized as highly studious, is a specifically relevant example of misrepresentation.

“Growing up, I wasn’t disturbed by [Baljeet’s portrayal], but I never felt connected to it either,” Hinkin said. “Now, I see how offensive it is. I loved [‘Phineas and Ferb’] as a kid, and it would have been cool to see an Indian character who had depth beyond just school on one of my favorite shows.”

Hinkin said a character whose entire personality is based on their ethnic identity is a disingenuous portrayal. She said that true diversity should both inspire those who identify with a character and educate those who come from other backgrounds. Hinkin said ethnically diverse and LGBTQ characters are often portrayed in a dehumanizing manner and are given stereotypical names and traits.

“For a long time, characters of color or characters in the LGBTQ community were used as comic relief, and [these portrayals] upheld the idea that those groups are to be laughed at,” Hinkin said. “True representation serves to dismantle stereotypes and empower people of all ages who want to see someone that looks like them on a screen or a stage.”

History teacher Erik Wade said diversity in media should stem from a genuine, positive place and should inspire those who identify with the character shown. Wade said actors of color are often pushed aside in the media and movies to make room for their white counterparts.

“People of color want to see themselves in different roles that they see white men and women in,” Wade said. “Why can’t we play all kinds of roles? Why do we have to be stuck in problematic, minimal roles that only make white folks shine? Why can’t we be the superheroes who are going to save the day?”

Wade said the representation in the movie trilogy “Fear Street,” directed by Leigh Janiak, felt inaccurate and avoided racial discussions despite including two Black characters.

“The writer could have added the texture of the erased experience of the Black kids within that context,” Wade said. “If you’re not going to actually grapple with [race], why not just make these kids white? It didn’t match experiences I had being Black and being a kid in 1984. If you’re going to [include diversity], then you’ve got to write it with as much authenticity as possible.”

Hinkin said to her, tokenism is the inclusion of a diverse character to create the illusion of inclusivity. She said it is easy to tell when a character was included for the sole purpose of avoiding criticism.

“Tokenism is lazy, condescending and super obvious,” Hinkin said. “It reflects bad writing and thus [creates] a bad show or movie. It’s so easy to have well-written diverse characters, and the answer is to have diverse writers.”

Like Hinkin, Herrera said tokenism is often noticeable and shows a lack of authenticity. She said token characters’ stereotypical names and personalities clue into a writer’s lack of research and reflect an inability to characterize a person beyond their racial or sexual identity.

“Often, writers who [include diverse characters] for ‘clout’ describe their characters stereotypically and separate them from their humanity,” Herrera said. “I can tell when an author is being genuine because they don’t bother to put in those stereotypes, and they actually develop the character beyond their basic traits and physical attributes. They’ll give the characters hobies, emotions and interests.”

Rustom Malhotra ’24 said writers who depend on tokenism fail to create diverse stories, and said he believes they should establish the character’s role beyond their race.

“It’s obviously important to be diverse, but you shouldn’t [feed stereotypes] just to say you have one diverse character,” Malhotra said. “I remember seeing shows and movies when I was younger with characters of my own ethnicity that I saw as stereotypes, and I bet that occurs for people of all races and genders.”

Additionally, with the rise of cancel culture, Hinkin said she believes writers feel pressure to diversify their casts for the public, leading to poorly-written characters. She said cancel culture is ineffective in achieving its original purpose and may benefit the “canceled” person.

“Celebrities’ names being in the news helps them,” Hinkin said. “I can’t think of a single person who was ‘canceled’ for something trivial that didn’t end up bouncing back in some capacity, even if it meant making money off of their infamy.”

Ofek Levy ’23 said cancel culture is unproductive even if it stems from social awareness. He said cancel culture restricts debate and leaves little to no room for nuanced discussions.

“Cancel culture doesn’t set up a productive environment for conversation,” Levy said. “It sets strict rules on what is acceptable and what is not, and anything outside of those is not even open for discussion. It leads to silencing more people than it [leads to] creating and encouraging diversity.”

Levy said increased visibility of marginalized communities in the media can help them feel included in society. He said although the effects of negative representation are not always obvious, addressing them can uplift underrepresented groups.

“The thing about lack of representation is that you don’t realize how it has negatively impacted you until you find great representation,” Levy said. “Positive representation creates a sense of empathy with one another. The feeling of finding someone you can connect to in media and TV is such a wonderful feeling, and you miss out so much when you can’t do that.”