Not Your Costume

Students discuss their experiences with and opinions on racially-insensitive Halloween costumes

October 17, 2021

Indian American student Anika Kumar ’23 said she never understood why some students choose to wear other cultures’ garments as Halloween costumes. Kumar said, given the variety of options to choose from, dressing as another race is unnecessary and offensive.

“Halloween costumes based around culture are inherently problematic, as you diminish an entire culture to a costume,” Kumar said. “A person’s heritage isn’t something you can or should dress up as for fun. These costumes are based off of a stereotype. There is no way to be another race while being respectful. It isn’t possible. Just don’t do it, especially when [there are] tons of other options that aren’t racist.”

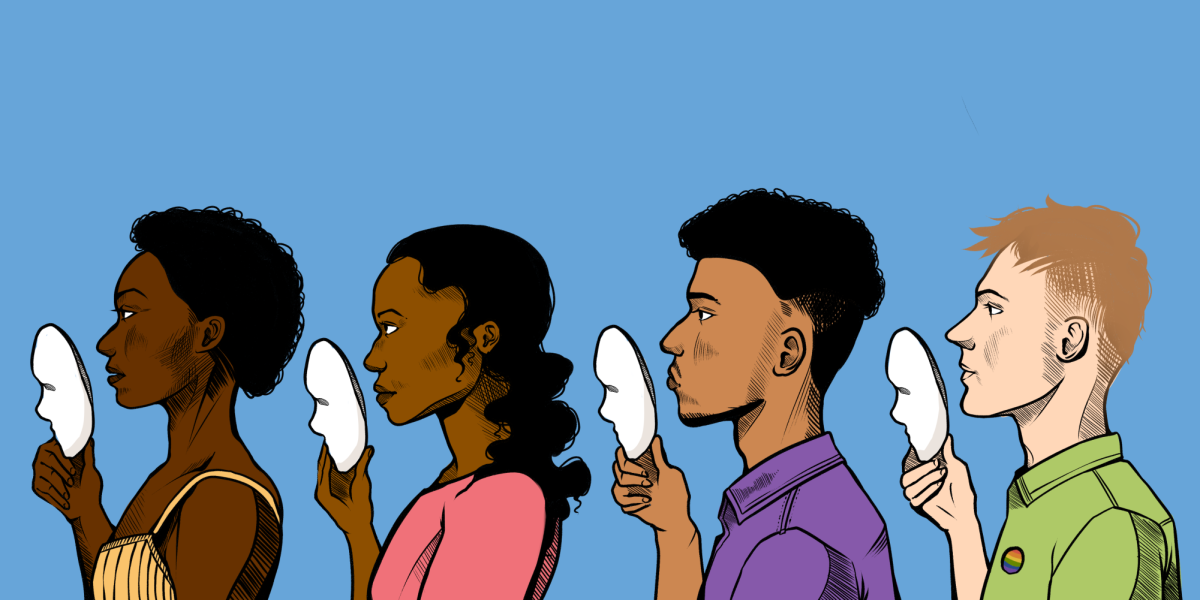

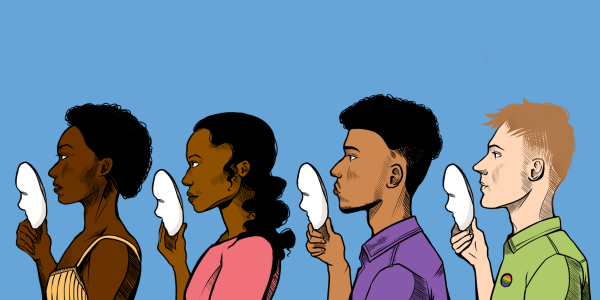

Halloween costumes that impersonate marginalized communities represent an aspect of cultural appropriation, which Webster’s Dictionary defines as the reclaiming of another culture’s identity and failing to credit its origins.

Often, these costumes emphasize sexualized elements of traditional garments, such as lingerie-qipao hybrids or skin tight Native American outfits. Attire relating to terrorism, Islamaphobia and the Holocaust is also readily available for purchase. For example, costume manufacturer Candy Apple sells a children’s Anne Frank costume.

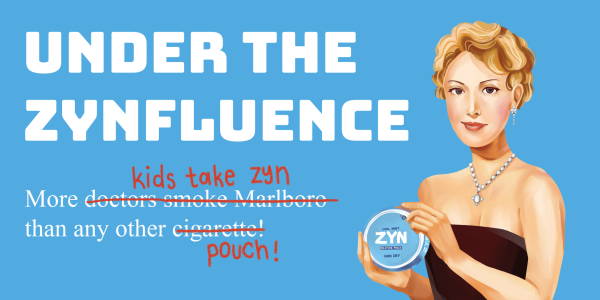

Backlash against these costumes has demanded companies do better to represent minorities accurately

For the last ten years, resistance against stereotypes and cultural tragedies has led to significant change in the Halloween costume marketThese campaigns include virtual advertisements, informational videos and historical education on cultural insensitivity. For instance, Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group (LSPIRG), a nonprofit that sponsors student activism, began the hashtags “#IAmNotACostume” and “#NotYourCostume,” two social media campaigns sharing information about costumes that misrepresent people of color.

Colombian American Venture leader Sophia Rascoff ’23 said no business should profit from glamorizing harmful stereotypes. She said while businesses capitalize on these images, the propagation of these ideas is the root of the problem.

“White-owned companies should definitely not profit from stereotypical costumes from characters,” Rascoff said. “This problem goes higher than costume companies–it is incredibly important that as diversity is added into our media, writers and creators are especially cognizant and avoid playing into stereotypes and offensive characteristics.”

Rascoff said she hopes children can enjoy Halloween without unknowingly perpetuating racist imagery. She said much of the ignorance in the media could be avoided by encouraging people of color to play larger roles in the creative process.

“When it comes to [children’s] characters, as long as people of color are involved in the creation process, it’s great to create these costumes for all kids to dress up in,” Rascoff said. “The main problem comes either when the character itself is a stereotype or when the costume company makes a generic costume that in itself is a racial stereotype.”

While Rascoff highlighted the importance of corporate awareness and cultural sensitivity, Student Leaders for Inclusion, Diversity and Equity (SLIDE) and Latin American Hispanic Students Organization (LAHSO) co-leader Cionnie Pineda ’22 said she hopes students understand the impact these costumes have on each person of color. Pineda shared an experience from her first Halloween after transferring to the school as a new ninth grader: she said she was taken aback and disappointed by her peers’ costume choices that year.

“I remember this one time a kid almost got in trouble for dressed up as a cholo [Mexican American gang member],” Pineda said. “He told the deans he was dressed up as a rapper, but culturally, that is what a cholo would wear. I don’t know if the administration was aware of which cultures wear what, but they didn’t give him detention or any punishment. For me, it was really upsetting that nothing happened because the kid is white.”

Nigerian American Black Leadership Awareness and Culture Club (BLACC) co-leader Eghosasere Asemota ’22 shared a similar experience. Asemota said he grew up taking note of his peers’ costume choices. He said, often, he didn’t like what he saw.

“I would see white students dress up as cholos or Black people,” Asemota said. “It is very hard to use a culture as a costume without reducing the meaning of the culture, and it’s especially wrong to mock marginalized communities for fun. This case was an example of that, in which these costumes were meant to be jokes, which made them even more disrespectful.”

While Pineda and Asemota both encountered students dressed as cholos, they highlighted other ways that people appropriate Latino culture on Halloween. The costumes in question continue to be sold online and in person, donning names like “Mexican Hot Tamale,” “Saucy Senorita” and “Bandita Shot Girl.”

Students express their disappointment with racial misrepresentation and sexualization

Cultural appropriation on Halloween appropriates more than Latinx culture: before encountering any traditional Asian garments, searching “Asian Costume” into Google provides results such as “Sexy Japanese Geisha,” “Sexy Asian Girl,” and “Sexy Oriental Cosplay.” Asian Students in Action (ASiA) co-leader and Senior Prefect Joy Ho ’22 said these outfits diminish the increased rates at which women of color experience sexual violence.

“Sexualized race costumes for Halloween are incredibly detrimental and problematic for those cultures and communities,” Ho said. “These outfits neglect the painful histories of sexual violence and further dehumanizing stereotypes women, reducing them to sexual objects. One big issue is that, even with so many campaigns fighting for an end to targeted racial costumes, we tend to separate this advocacy from defending the communities themselves. One major example of this is the lack of attention on violence against Indigenous women even with backlash when it comes to people wearing Indigenous peoples’ costumes.”

According to VAWnet, a database from the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, Native American women are 2.5 times more likely to be victims of sexual assault in comparison to women of all other races, and 34% of Native American women are raped in their lifetime. Ho said she is deeply disturbed by the continued production of sexualized Native American costumes and the violence costume wearers perpetuates.

Japanese American student and Junior Prefect Aiko Offner ’23 said she is upset by all race-based costumes but finds the sexualization of Japanese uniforms particularly pedophilic and disturbing. Offner said she spends nearly half the year with friends and family in Tokyo, and she was surprised and mortified by how foreign industries interpret Japanese culture.

“To sexualize what students actually wear is disturbing and disrespectful to Japanese culture and people,” Offner said. “If I were going to a Japanese school and saw that foreigners were wearing sexualized versions of my school uniform, I’d feel violated and objectified. These shortened skirts and tops aren’t actually what students wear but kept the same design elements to specifically sexualize young Japanese girls. I know these outfits are also based off of sexism and [the] general weirdness of certain anime, but we don’t see as many sexualized Western or European schoolgirl outfits. It’s all pedophilic, but [it] particularly reflects the perverse ideas about virginity and innocence associated with Japanese and East Asian culture.”

Chinese American student Joshua Cheng ’23 said he is more concerned with the actions of the wearers of the Asian-inspired costumes rather than with the costumes themselves. Cheng said, while he understands that many people born and raised in Asia love when foreigners wear traditional garments, he takes issue with the racist accents and gestures that ensue.

“I’m all for a white kid dressing up as Bruce Lee,” Cheng said. “I dressed up as Bruce Lee. He’s awesome, but if a kid starts squinting his eyes and doing racist accents, he’s gonna turn into the type of person that Bruce Lee would beat up.”

Cheng also said, while physical gestures like eye-pulling are often clearly racist, the subtleties in one’s intentions are often equally revealing.

“Dressing up as an ethnicity or nationality feels very wrong, but dressing up as Asian American characters is fine,” Cheng said. “It’s really the intent that matters. Is this person dressing up as this character to make fun of the character or are they genuinely a fanatic of their story and background?”

Students encourage others to properly appreciate cultures, rather than appropriate them

African American student Samuel Hines ’24 said heritage is more complex than one night of dress up, and he encourages students to explore these cultures in considerate ways.

“I believe that a [group] that is not subject to the cultural, ethnic or religious background of the culture-oriented Halloween costume they are wearing is very insensitive and in many cases, offensive,” Hines said. “As someone who enjoys expressing myself with clothing, I would suggest [that] those who are interested in wearing costumes that represent other cultural backgrounds and ethnic groups seek relation to them in other forms.”

Chinese American streetwear brand ShopJaydenHuang owner Jayden Huang ’23 said incorporating traditional Chinese details in his designs and learning from other cultures in developing his fashion sense has become second nature. Like Hines, Huang said clothing is an essential aspect of his self-expression. He said he strives to be inspired by other cultures in the most responsible way possible.

“While the conversation for what is appropriation and what is appreciation is highly debated, I think one major rule is to always make sure you are crediting the right people,” Huang said. “Don’t wear a qipao from [clothing company] DollsKill and call it a ‘silk dragon dress’ just because you saw Kim Kardashian wear a similar one. Personally, my everyday outfits are heavily inspired by many trends from the 2000s, and particularly Black stars I love and admire. Beyoncé, Lil Kim, Aaliyah, Missy Elliott, Kimora Lee Simons and so many more laid the blueprint for the trends we see now.”

Huang said, while these celebrities have influenced his wardrobe, there are certain aspects of their style he cannot adopt, like hairstyles. He said he hopes others can recognize the cultural significance of an article of clothing before impulsively appropriating it.

“It’s important to note that some cultural pieces of clothing are not meant to be worn by others and that sometimes the best way to appreciate another culture’s clothing is to simply admire it, not wear it,”

Huang said. “Often people have good intentions when paying homage to a culture, but if your actions end up hurting people from that culture, then the intentions don’t matter because harm was done.”

Huang said dressing as another race is wrong and unnecessary, given how many other Halloween costume choices are available. Huang said students should stick with outfits the character wears and not attempt to alter their appearance to match a character’s race.

“Do not try to emulate the features that any character of color might have,” Huang said. “Don’t use darker foundation or use eyeshadow to try to make yourself have smaller, more slanted eyes. If the character you want to dress up as has an afro, don’t curl your hair to make it look like you have an afro too. If you do, or if something happens, make sure to be understanding that some people will find things offensive that you did not think of, and that it’s okay to admit you’re wrong and learn from your mistakes.”

Mexican American LAHSO member Fernanda Herrera ’23 said she also condemns people altering physical attributes to dress as another race. Hererra, who didn’t grow up trick or treating and attended predominantly Hispanic schools, said she became aware of culturally insensitive costumes fairly recently. She said the imitation of another culture is both confusing and disrespectful given the various options on the market. She said she does not understand why someone would glamourize struggles they do not face.

“Now that I’m older, seeing these costumes just makes me angry,” Hererra said. “I don’t see my culture differently, [but] it makes me upset that others would think my ancestry can be put on and taken off [through costuming]. These people can be a ‘drunk Mexican guy’ for one night and then continue to live their privileged lives. Actual Hispanic people who are stereotyped that way cannot go home and take their skin off.”

Hererra, a member of the Get Lit Players, said she tells many stories about her culture in poetry. She said heritage is not something that should be encapsulated in a Halloween costume but instead honored in more comprehensive ways.

“I think culture is art,” Hererra said. “Everything, from our unique celebrations, to the way my grandmother kneads dough, to the bead necklaces indigenous communities make is art. Culture and art don’t just intersect. They are almost always indistinguishable from one another. The way my grandparents talk to me, the early morning masses I hated attending as a child, the loud chatter of aunties gossiping: it’s all poetry. That poetry is written on the architecture of our buildings, the way our food looks in pots and pans and of course, our traditional garments. It’s all art.”