More Than a Month

Members of the school community reflect on Black history and Black activism during Black History Month.

Since 1970, the United States has recognized February as Black History Month.

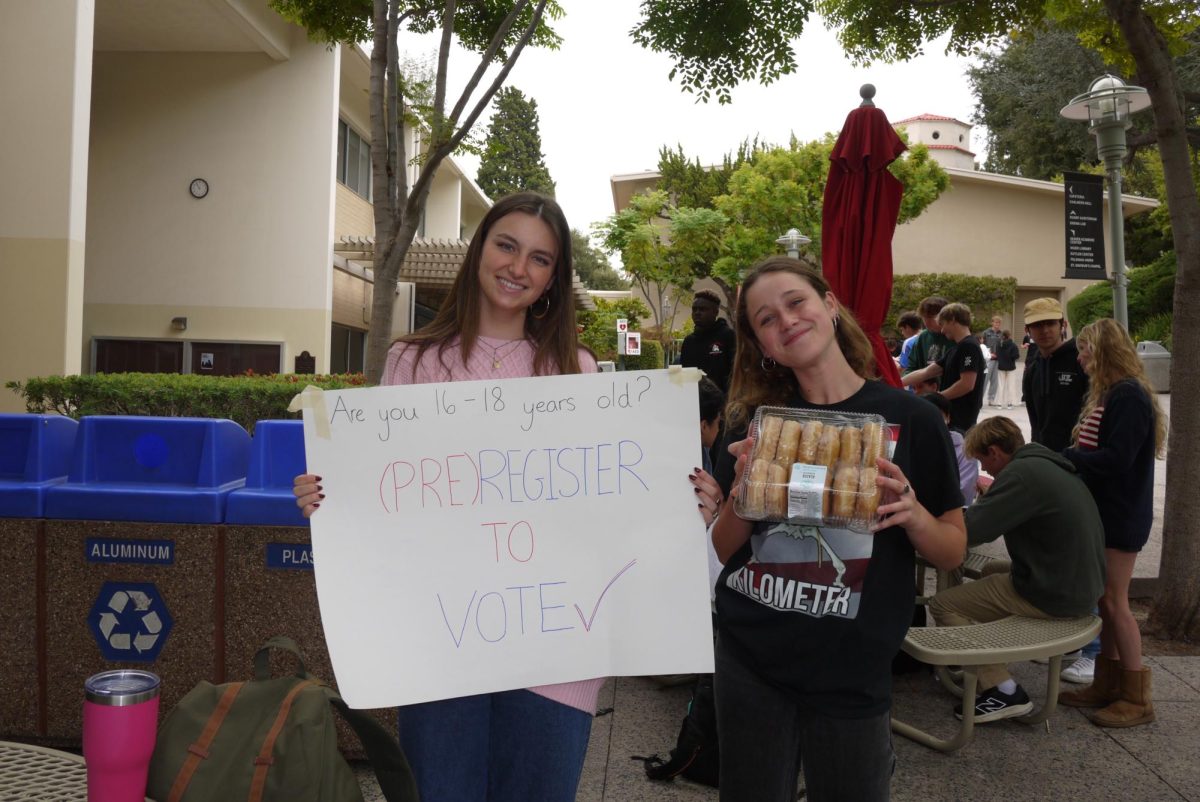

Since 1970, the United States has recognized February as Black History Month. The observance is now recognized in Canada, Ireland and the United Kingdom. However, for Zenmarah Duruisseau ’22, the celebration of Black History Month is not limited to the 28 days of February.

“[Black History Month] is every month, every week, every day, every hour and every second,” Duruisseau said. “I choose to celebrate my Blackness and Black history all the time. I feel like this month just allows more people outside of our community to view us. Black History Month is a time where I can truly show how proud I am of my people and culture, but I don’t [restrict] this to a single month. I do this every day, all day.”

Duruisseau said the Black experience is unique for each Black person. She said she celebrates her identity by resisting negative stereotypes that others place upon Black culture. Ranging from larger-scale movements to raise awareness for Black issues to how she integrates her culture into her art, Duruisseau said she actively combats anti-Blackness.

“Black usually has a negative connotation, representing evil or darkness or even despair,” Duruisseau said. “To me, this is untrue. In my opinion, Blackness is hard to define. It’s everything. It’s power and beauty, it’s even happiness. I don’t associate negative things with the word because it’s also the word for my race. I see my mom, my aunt, some of my friends and mentors when that word is spoken. I see history and art resilience. The stereotypes many are confined to do not define what it means to be Black. Blackness is unique to the individual. That’s why we are such a diverse and amazing group of people.”

In school, Duruisseau said she takes classes about Black history and develops research projects and independent studies about her culture. As a dancer and choreographer, she said she highlights the Black experience through Black styles, dance moves and the storytelling in her pieces.

“I feel like advocacy and my craft intersect,” Duruisseau said. “As a choreographer, I create pieces about Black history, the Black struggle and Black excellence. I am either trying to educate my audience about a topic, inspire them to create change or encourage happiness in times when it is so hard to be.”

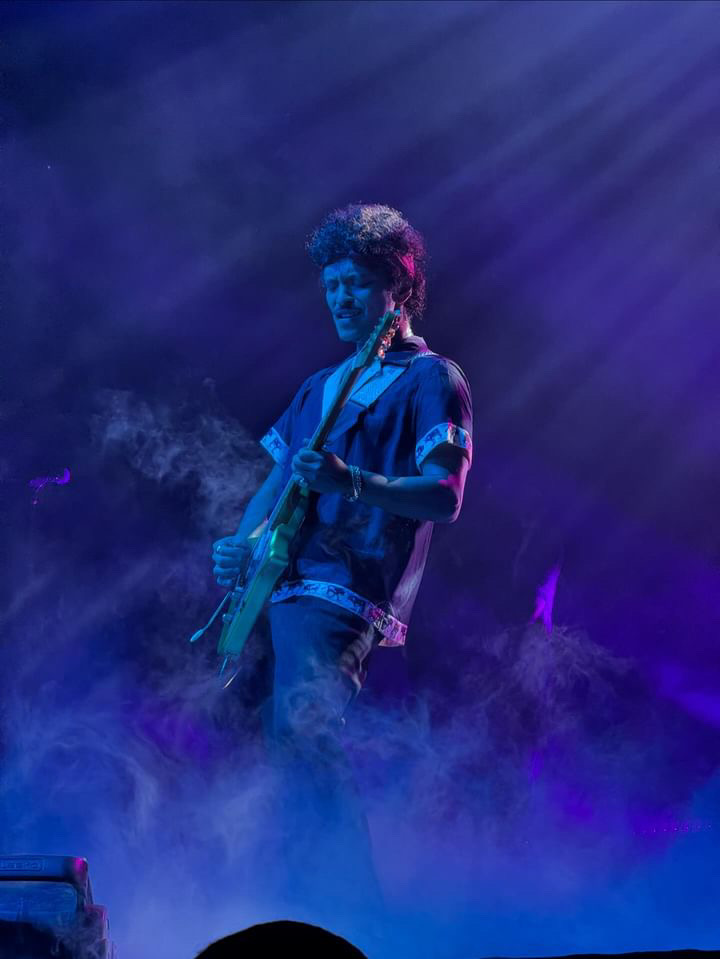

Black Leadership Awareness and Culture Club (BLACC) leader, Student Leaders for Diversity and Equity (SLIDE) co-leader, Westflix leader and filmmaker Santiago Kelly ’22 said he advocates for Black issues through the clubs he participates in and the projects he creates. For the most recent Video Art 3 showcase Jan. 19-28, “The DUALITY of REALITY,” Kelly portrayed his film “Endangered” by using two monitors to depict tensions between African American men and law enforcement. The film’s first panel features BLACC member Tosa Odiase ’22 walking and eventually running away from an entity unknown to the viewer. The second panel, shown simultaneously, features a faceless form of BLACC member Milo Kiddugavu ’22 in a police uniform, pursuing a figure assumed to be Odiase.

Kelly said the intent of his art is to open students’ minds about the meaning of art and to bring attention to important issues.

“My main objective when creating socially-engaged art is just to bring awareness to the issues that continue to plague our society,” Kelly said. “I like to show new ways of exploring our problems through shifting lenses and perspectives. I just hope to open people’s minds to what art means and how it can move people and reflect reality.”

When envisioning the future of Black activism, Kelly said he predicts both art and legislation will take stronger roles in the push for racial equity.

“I anticipate all art from Black artists and surrounding Black issues to continue to become even more illuminating and profound while even more concerted efforts are made towards undoing the racial, structural damage of this country from a legal standpoint,” Kelly said.

Head of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Janine Jones (Avery Jones ’23) said Black activism and discussion about Blackness should not be treated as a monolith and, in order for progress to be made, individual and systematic efforts must recognize the diversity within the Black experience.

“Blackness is what an individual who is Black defines it to be for themself,” Jones said. “As someone who is African American, when I was younger, I used to have these ideas of what Blackness was that were much more concrete and limited in scope, but as I’ve gotten older, and especially as I’ve been leading DEI work, I can’t answer [what it means to be Black]. It is up to every individual who identifies as Black to define what Blackness is.”

When reflecting on Black History Month specifically, Jones said her feelings change every year. While she said she appreciates the more organized efforts to honor Black heritage, she also recognizes the national divisions that prevent productive conversation about race.

“There is a part of me that loves [Black History Month] because as a Black person it’s always wonderful when you are in communities where you are not in the racial minority to see your identities celebrated by everyone or by a lot of people,” Jones said. “However, given our polarized times around issues of race, I worry about the politicization of Black History Month, particularly this year. I’m going to choose to see the positives and the fact that we are celebrating it.”

Jones said when she imagines the next steps of Black activism, she reflects on the progress that brought the country to this point of racial equity.

“It’s hard to imagine the future of Black activism without thinking about the past and thinking about how Black activists have successfully worked for change in this country,” Jones said. “The future is bright, but it is going to continue to be hard. I don’t want the burden to fall upon Black people to fight for Blackness to be recognized, just like I wouldn’t want the burden to fall on any other marginalized community to fight for their own humanity to be recognized.”

Black Kids Who Care (BKWC) co-founder Ava Robinson ’23 said she helps unify and lead young activists through the program, which raises awareness to Black issues and organizes community service events to give back to the Black community. The program’s Instagram account, @b.k.w.c, has amassed over 6,000 followers since its creation in May 2020 and shares news and information about Black history and quotes from notable Black figures.

“Our main purpose is to spread awareness about the injustices Black people face on a daily basis, big and small,” Robinson said. “We also thought it would be very important to start an organization strictly run by Black teenagers to help inspire other Black teenagers to speak out and create change. We wanted to create a safe space for everyone to discuss the hard truths of being Black in America but to also celebrate the importance of Black culture around us.”

BKWC co-founder Christopher Spencer ’23 said he agreed with Robinson, adding that raising awareness to Black issues during Black History Month is particularly important to the organization’s leaders.

“Black History Month is a time where we get to share historical Black figures who might not get the recognition they deserve,” Spencer said. “I want people to understand that just because we have a month doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be celebrated throughout the whole year.”

BKWC co-founder Judah Marley ’23 said she hopes the account can shed light on diverse issues within the Black community and create progressive conversations within Black teenagers.

“We use our account to educate and spread awareness about issues within our community, aiming to reach kids like us who can help educate even younger generations and create a positive cycle of education and enrichment of our history, both the good and the bad,” Marley said.

Marley said her own perception of being Black is nuanced. She said while systematic racism creates more difficulties when it comes to expressing and celebrating Blackness, she is proud of her identity and rich culture.

“I would define Blackness and [being] Black as a beautiful struggle,” Marley said. “Although it can be difficult, it is one of the most beautiful things in the world. Being Black means that I will always have my people behind me and there to help me out and back me up. It is a huge part of my identity and affects everything from my family to daily interactions. It also means happiness because being a part of and uplifting this community makes me happy.”