Enlisting for an Education

March 22, 2023

In her third grade classroom, Natalia Johnson ’23 said she was always amused by her teacher’s antics. Every time she got a name wrong, Ms. Anderson would drop to the floor and do thirty five push-ups. Though Johnson didn’t know it at the time, Ms. Anderson’s background as a military veteran would go on to play an influential role in Johnson’s own life. Today, Johnson is set to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, a goal she said she has been building toward for her entire life. According to the school’s matriculation data, only three students at the school have attended West Point in the last five years, but Johnson said she feels comfortable attending a service academy.

“One thing I like about service academies is that everyone’s more well connected and knows each other afterward,” Johnson said. “I wanted to be a part of West Point in particular because it has a long history, and there are a lot of great people there. I knew that a civilian college wasn’t right for me, so I wanted to go to a place that fully captured the military culture.”

According to the West Point website, service academies differ greatly from conventional colleges. The largest difference is that all students who graduate are required to serve in the military for at least eight years. To prepare for this, students are required to participate in military training and play a sport, while also maintaining a rigorous academic schedule. Because of the service components, all students attend school for free and even get paid $1000 every month for expenses such as laundry, books and activity fees. After graduation, all students also immediately become a second lieutenant in their branch. West Point receives many applicants, but it only lets in 10.7 percent of them each year, according to U.S. News and World Report. Johnson said much of this is because of its unique application, which contains many difficult requirements.

“I think it’s around an 80-hour application, and that’s only if you’re applying to one academy,” Johnson said. “You have to get a nomination from a congressman, a senator or the Vice President, which is very rare. You have to pass their medical [exam], and then you have to pass their fitness exam as well. That’s all in addition to the regular essays. I was lucky to get my congressman’s nomination, so I wasn’t stressed about getting one from a senator.”

Johnson said her dean had to learn about the school with her during the application process since applying to a service academy is not common at the school.

“My dean was doing research along with me because the school doesn’t have any data,” Johnson said. “The application process is so different for service academies, so the deans actually had to do a lot of research as well to help me. I would recommend that there [be] more resources going towards service academies, because it’s a great opportunity, and I think a lot of Harvard-Westlake students would do well there.”

Despite this, Johnson said service academies have a bad reputation in the private school community, despite the excellent education they offer.

“There’s this misinterpretation that going into the military is what to do if you can’t get into college,” Johnson said. “It’s like your second option, but it’s really not. There are so many intelligent people, and you’re basically getting an Ivy League-level education and all this training for free. So it’s really an opportunity that I think a lot of students, especially in private schools, don’t realize. I also knew that a civilian college wasn’t right for me. I wanted to [go to] a place that fully captured the military culture.”

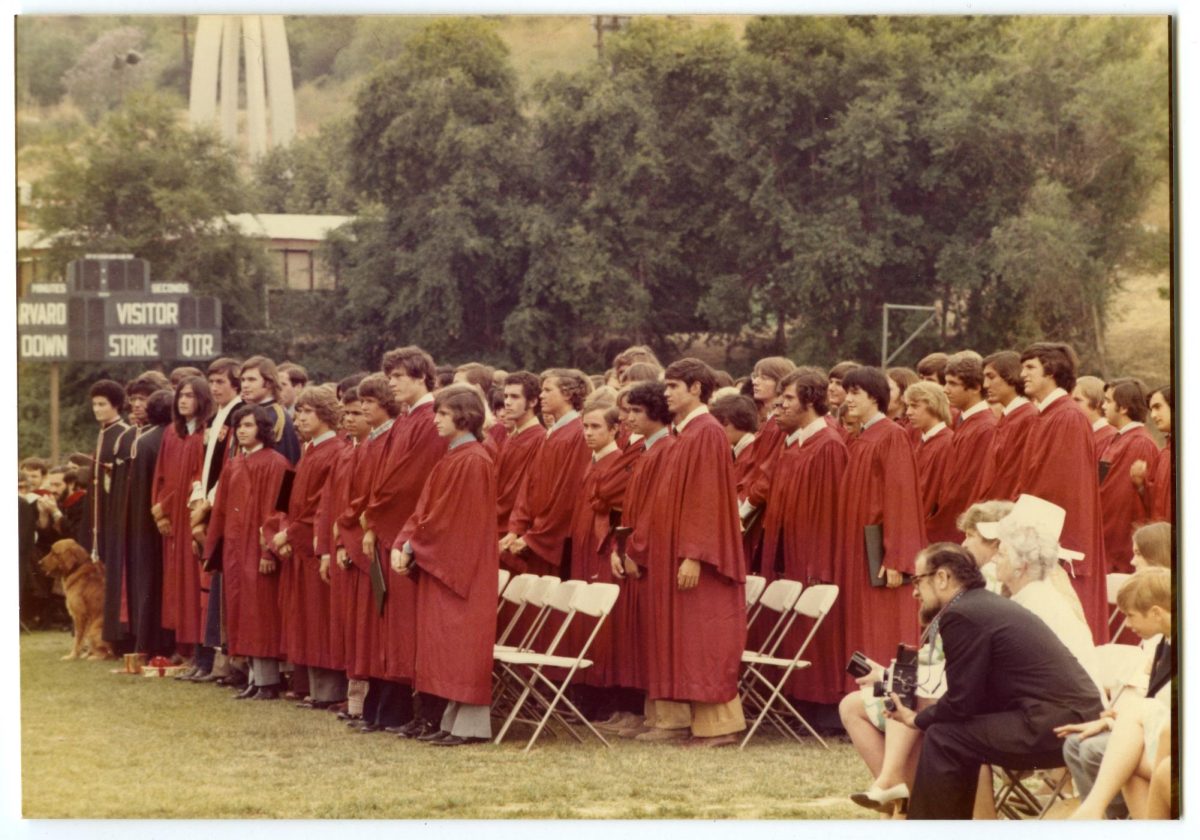

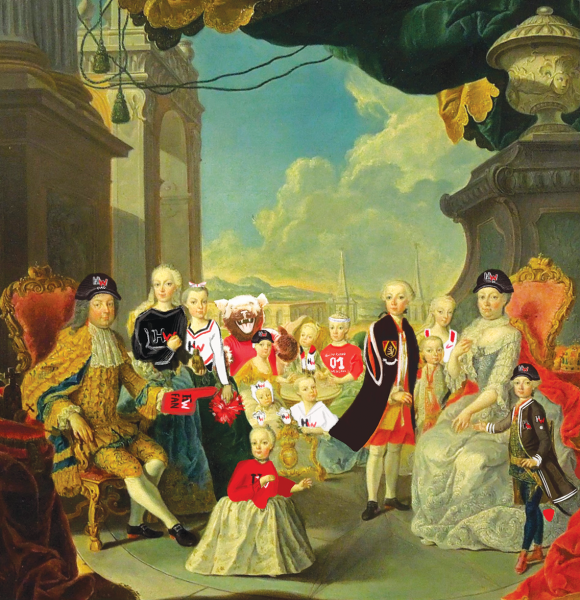

Colin Weidmann ’08, who attended West Point 15 years ago, said he was also enticed by the great education offered by the school.

“For me, [going to West Point] was about the great education,” Weidmann said. “West Point is the fifth highest producing Rhodes Scholar school of any college in the country, which a lot of people don’t realize. I also wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do, and it was an opportunity to do something a little bit different, which I’ve always enjoyed. I now have 11 total years in [the military], so I didn’t look at that five-year commitment as a negative.”

Once he arrived at West Point, Weidmann studied international relations and Chinese, eventually securing majors in both areas. Like all students at West Point, Weidmann also had extracurricular activities, which he said made the days grueling yet rewarding.

“I woke up at about 6 a.m. every day, and I had formation at 6:50 a.m.,” Weidmann said. “At West Point, you take a lot of classes relative to a normal college schedule. I probably averaged like 20 credit hours while I was there, and I also double majored. Everybody at West Point also has to play a sport, so I was on the club marathon team, and every afternoon, we would go do our running practice from about 3:30-5 p.m.”

Like all West Point students, Weidmann was immediately commissioned as an officer after graduation. After working in different positions for a few years, including deployment in Afghanistan, Weidmann decided to make the switch to special forces, a selective military unit designed to conduct operations with complex parameters. Weidmann said he enjoyed his time with special forces because it allowed him to experience his studies from a different perspective.

“Special Forces [is] probably one of the more intellectually rigorous jobs in the military,” Weidmann said. “We’re practitioners of international relations at the tactical level. So, on the ground, we’re in foreign countries working with foreign militaries, going to embassies, talking with different people. It’s a really cool application of what you learn in the classroom actually on the ground, in being able to think through some of those problems.”

When Weidmann first told his friend Jack LaZebnik ’09 that he was thinking about applying to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, LaZebnik said he didn’t understand the decision due to the school’s mandatory service obligation.

“Nobody joins the military coming out of Los Angeles, let alone Harvard-Westlake,” LaZebnik said. “I will never forget the first time he brought up West Point. I thought, why would you throw away your life like that? There’s a stigma that the military is where the rejects go.”

Just three years later, however, LaZebnik would find himself following in Weidmann’s footsteps. While there were many factors that influenced his decision to attend a service academy, LaZebnik said he was drawn to West Point because of the challenge it presented him with.

“There was a point [at] which I was looking around at other universities, but they all seemed more similar than they did different,” LaZebnik said. “When I considered West Point, I felt like I would finish that experience in four years and have been through the hardest experience of anybody from my high school or, holistically speaking, from the country. It gave me a lot of pride.”

After graduation, LaZebnik said he immediately entered the army as an infantry officer responsible for around 40 soldiers. When he was deployed to Afghanistan, his role became far more abstract, and he said he eventually found himself leading an undercover, two-person reconnaissance team. Although the work was challenging, LaZebnik said he felt prepared by the pressure he faced at the school.

“Harvard-Westlake makes you do really hard things, and that intense, pressurized process actually prepared me for West Point and the military because I knew that I had done hard things before,” LaZebnik said. “Maybe the pressure was turned up a little bit, but I could continue to do hard things, and that didn’t mean I was going to succeed every time, but it meant that I knew I had been there before and that I could do it again.”

Due to this connection with the school, LaZebnik said he decided it would be beneficial to bring back the military alumni network.

“I suspect that the majority of Harvard-Westlake students would actually be very interested in joining the military as a leader in an official capacity,” LaZebnik said. “It’s aligned with some of the professional and personal goals that Harvard-Westlake students have. The veteran alumni group that we have at Harvard-Westlake has people who served in every branch of the military and went to every military service academy. They would be happy to talk to Harvard-Westlake students and honestly tell them the good, the bad and the ugly.”

One member of this group is Earle LeMasters ’04, who didn’t attend a service academy. Instead, LeMasters said he participated in a Navy Reserves’ Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program at Northwestern University.

“I just did a traditional ROTC program,” LeMasters said. “I always tell people, it’s really kind of the same as being a student-athlete. You’re up early on some of the days for training and exercise, and all the while you’re getting ready to go be a part of the military.”

Similarly to service academy graduates, LeMasters said students who complete ROTC training enter the military as officers. Because of this added responsibility, LeMasters said the training consisted of both physical exercise and leadership classes.

“There’s a lot of times where we did team building exercises, and we did scenarios to understand how to work through tough situations,” LeMasters said. “You walk into the military, and day one, as a 22-year-old young kid, you’re put in charge of a group of 15-20 sailors that are ages 18-45, and you’re told to run their lives. Then in your off time, you’re told to go drive a $2 billion ship in the middle of the night while the captain is sleeping. You kind of get thrust into a lot of these very high pressure scenarios.”

In his current job at an elevator and escalator company, LeMasters said he uses many of the lessons he learned in the military to lead his employees.

“I have a much better perspective of working with all of the people that report to me,” LeMasters said. “And again, these are people who know the industry and know the company way better than I do, because they’ve been around for 15-20 years, but I’m still their boss, and they will sit there and listen to me.”

Student discipline and attendance coordinator Gabriel Preciado said joining the military was an alternative to a traditional college experience.

“[Joining the military] was a decision toget me out of the place where I was at,” Preciado said. “In my home area, there’s a lot of violence, there was a lot of drugs, the neighborhood was bad and I can’t say I had the best advice as far as going to college. I could have probably jumped into college, but I didn’t have any money, and I didn’t know that there was financial aid, so I figured my best opportunity was the military.”

Once in the Air Force, Preciado was an aerospace propulsion specialist at Edwards Air Force Base in San Bernardino, Calif., a job that consisted of quickly fixing planes and their engines. Preciado said this job gave him a different perspective on how to be efficient with time, a value that he carries into his work at the school.

“You see a lot of screens [in my office], and all of that is because of my competency in using tools to improve the way I do things,” Preciado said. “For the large school that we have, I have to be managing different things at once. At some of the schools, you would need more people, but the fact is that Harvard-Westlake is able to provide me [with] the technology here that I need to accomplish what I do through Didax and the iHW app, and it makes life easy.”

Aside from these advantages, Preciado said his favorite part of being in the military community at the school is connecting students with veteran alumni.

“I love to talk to the students who are looking into the military academies,” Preciado said. “I can really kind of guide them through their thinking, whether it’s a life that could be suitable for them. Sometimes I connect them with alums from the school like those who went to the academies. So I love that [serving in the military] has really helped me be a part of this community in that way.”

Head of Upper School Beth Slattery said she encourages students to pursue a school that caters to their interests.

“The truth is that the majority of the colleges and universities that our kids look at, are going to be a lot like the school,” Slattery said. “There are wonderful things about Harvard-Westlake, but in terms of academic stress, that’s not actually in everybody’s best interest. I think [service academies] feel foreign to a lot of our kids but should be celebrated. The idea that somebody wants to go someplace with that kind of discipline and make this commitment to service that extends past their graduation [is] incredibly noble.”