Content Warning: this article contains the usage of homophobic slurs.

On a cold afternoon in February 2008, Matthew Krumpe ’08, a senior at the time, had just finished dance class in lower Chalmers. Feeling ready for track practice, he changed in the bathroom and walked up to the Quad. This was a normal day for Krumpe —he had done this routine hundreds of times. However, the moment Krumpe stepped foot on the Quad, that afternoon was set apart from all the others. Immediately surrounded by 20 angry sophomore boys, Krumpe froze. He said he eventually realized these were the kids he had unknowingly reported for cheating on their history midterm that January.

“In my head I was like, ‘What is going on right now?’ Krumpe said. “They were all like, ‘What the f**k man? Why did you do this? You already got into college. You don’t need anything.’ I got a lot of, ‘You’re just a f****t. You shouldn’t be coming back to school. Nobody wants you here. ’ The whole time, I was just confused. I didn’t know what was going on, and then I was like, ‘Wait a second. These are the kids who cheated.’ The Honor Board was watching this whole thing go down. The kids admitted in public that they cheated, and that’s when [the school] started giving out suspensions and expulsions.”

Weeks after the test was administered, Krumpe, a peer tutor, was helping Hayley Boysen ’10 study for the same exam since she had been absent during the testing period. In one of their tutoring sessions, Boysen revealed to him that her friends offered her the compromised copy of the test. Krumpe said he advised her to report her friends, which he assumed would be the end of his involvement.

“I said to her, ‘What I recommend that you do is tell your friends to turn themselves in,’” Krumpe said. “Regardless, the kids who cheated were gonna get caught,but if they [turned] themselves in, maybe they’d be suspended, not expelled. We all know how serious the Honor Code is. That all falls apart if people are cheating. I ran into her about seven days later at school, and I said, ‘How are you? Did you do it? Did you talk to your friends?’ She looked me in the eye and said that she did, but I just knew she was lying. Her history teacher was my history teacher, and I felt obligated to tell him. That’s when the s**t show started. ”

Krumpe reported the incident to Upper School History Teacher Dror Yaron Friday after school a few weeks later. On the following Wednesday, the story was printed on the front page of The Chronicle. Weeks of investigations and Honor Board cases followed, resulting in the expulsion of the six directly involved students and the suspension of 12 others who used copies of the test.. The story received attention from several major news outlets across the country. Krumpe said trust between teachers and students experienced a large shift following the scandal.

“It was a very tense year versus other years at the school,” Krumpe said. “It affected the teacher population because they felt like their trust was broken, and they felt violated in the way that they had to make sure that doors [were] locked when they’re making a photocopy. There weren’t any major cheating incidents the rest of that year, but plagiarism was still big. I knew kids who copied papers from previous people . There’s a pressure cooker environment at Harvard-Westlake. Some people can’t handle the pressure, so they’re gonna stoop down to things like trying to cheat.”

Prefect Council wrote and implemented the school’s current Honor Code in the late 1990s. One part of the code states that students are not to “steal or violate others’ property, either academic or material.” Upper School Dean Sharon Cuseo said teachers became more cautious about cheating following the scandal.

“There was less trust on the part of the faculty after [the cheating scandal],” Cuseo said. “For the most part, unless they’re given a reason to be suspicious, teachers are not that suspicious. Immediately after that, [however], teachers were not willing to let students take tests by themselves or let one student take a test before another class did. The incident had an impact on trust.”

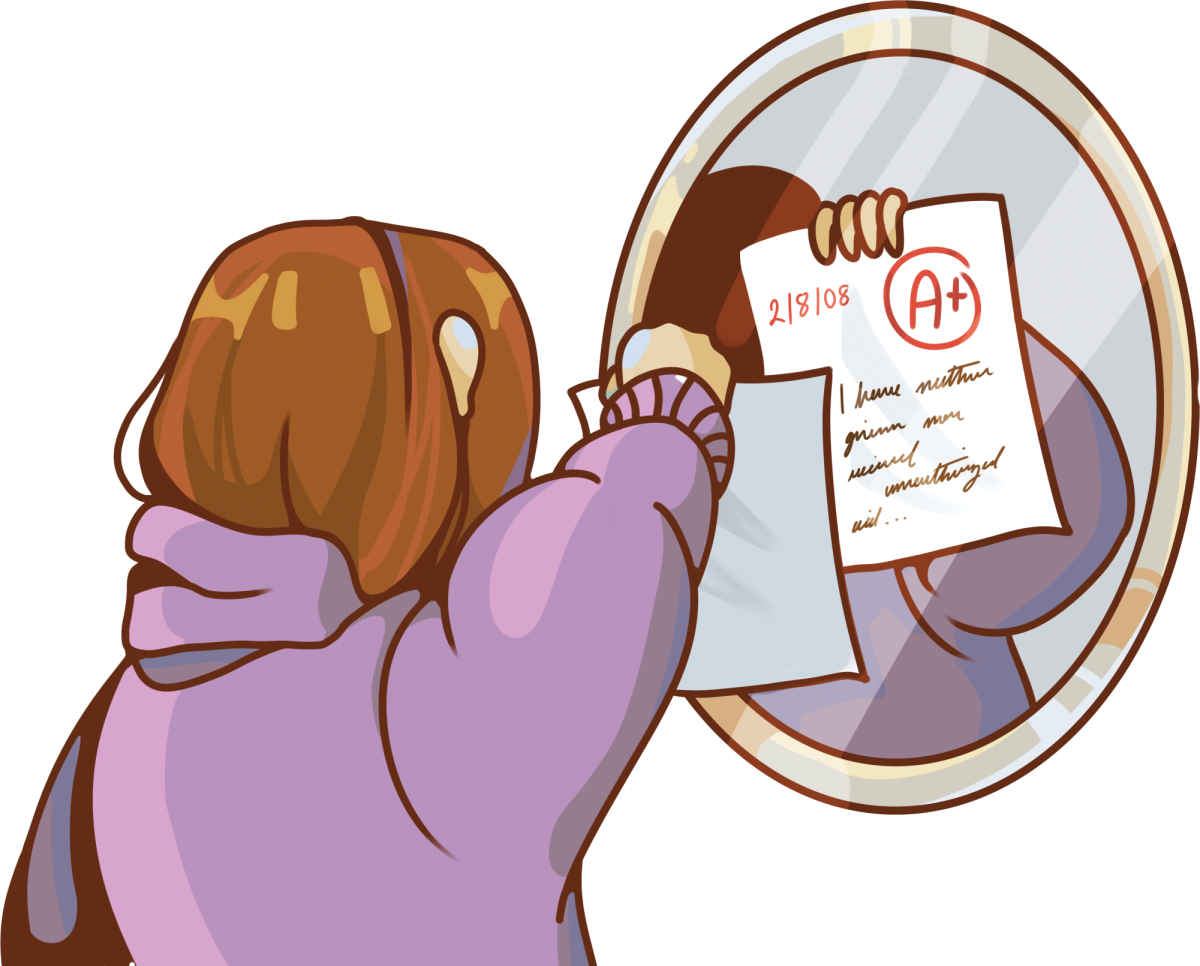

According to a Chronicle poll, 40.5 percent of students have cheated at least once during their time at the school. Cuseo said most students do not make premeditated plans to cheat on assignments, and cheating often happens when a student feels that it is their only option.

“Anybody under the right circumstances could make a bad decision ,” Cuseo said. “The hard part for [a] Harvard-Westlake student [who cheated] to understand is [that] in a moment of desperation, [they] took a shortcut and gained an unfair advantage . They think, ‘What I did couldn’t be cheating because I’m not a cheater. I’m not [going to] make a plan to steal a test.’ But [cheating] usually happens late at night because they’ve procrastinated, and that’s when they realized that they needed something that wasn’t authorized.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the school conducted classes online, and students took all assessments at home. Cuseo said the school noticed a rise in students cheating, causing students to become distrustful of their students.

“The thing that broke all of our hearts a little bit during the pandemic was [the] lack of moral clarity,” Cuseo said. “The opportunity to cheat was there, and it was too tempting. There was so much cheating, particularly with math. We had a rash of Photomath situations because it was right there, and no one was watching. After COVID, teachers in all departments thought when given the opportunity, a lot of kids might cheat. Now, we have more of a problem with people not showing up on the day of a test.”

In Spring of 2022, Advanced Placement (AP) Statistics classes took a one question multiple choice quiz daily called the Probability of the Day. The quiz was taken on The Hub for 45 days, if a student got 30 of them correct, their lowest test score would be changed to a 100. Kendrick*, a sophomore in college, said he helped a majority of his classmates cheat on the quizzes by posting the answers on Instagram.

“[The Probability of the Day] was the same question for everybody, so same numbers, same prompt, literally the same question and [canvas] would tell you the answer [after] one attempt,” Kendrick said. “I was someone who liked stats and did well in stats. I don’t remember how I justified doing it to myself, but I realized that I could help everyone in AP stats by doing the question and getting it correct. I put the answer in my Instagram bio and then I disguised it as a Bible verse. I ended up ruining the entire Probability of the Day for everyone because [the school] had no way of telling who actually [cheated].”

Kendrick said he admitted the truth about his involvement after he was questioned by his teachers.

“The stats teachers got wind of me doing it, or they heard from someone talking about it on the quad,” Kendrick said. “I never asked [how they found out] because it really didn’t matter at the time, but they just found out and then they hauled me in. They basically sat me down and didn’t know the full extent of it, but I came clean. I kind of justified it to myself as something funny, like a harmless troll. It proved not to be harmless at all. I think after the first couple of days, it was just part of my routine. And then obviously I realized in retrospect how bad it was, but at the time it didn’t really cross my mind.”

When a student is caught breaking the Honor Code, their case is dealt with by the school’s disciplinary body. The Honor Board is usually comprised of both Head Prefects, two prefects from each grade, Dean of Students Jordan Church and various faculty members who decide on punishments for violations of the Honor Code. The process is meant to focus on rehabilitation rather than purely focused on punishments, according to Head Prefect and Print Managing Editor Davis Marks ’24. Kendrick said he was grateful that his peers were deciding on his case because they were able to understand his perspective.

“Part of one reason why I didn’t get severely punished and [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] never found out was because I think having my peers, faculty, kids in the grade below me and kids in 10th grade sitting in humanized the process a little bit,” Kendrick said. “They understand what it’s like to be a teen and what it’s like to make very impulsive decisions because you think they’re funny or because you think you’re helping your friends. So I was thankful that [students] sat on [the Honor Board] and I think it was a really good and important part of the process.”

Last year, the English Department made the decision to get rid of take home essays due to the rise of ChatGPT. This year, all English essays are taken in class and written by hand. Upper SchoolEnglish Teacher Eric Olson said there are reasons besides ChatGPT that account for the department’s shift away from take-home essays.

“Since I’ve been here, there has been an ongoing conversation about how we make sure we’re getting authentic work, and it’s only gotten harder in the last year,” Olson said. “It is not a fair process if we have students who are getting tutors to help them write papers at home, and we have students whose parents can barely afford to keep them in the school [and] are doing the best they can, and I’m assessing each paper the same way. What we’ve done this year with getting rid of take-home essays has been a long time coming. ChatGPT is just the straw that broke the model of what we were working with. The idea that we could give students the chance to go home and write on their own was thrown out the window.”

Olson said the extent of cheating remains consistent whether students resort to tutors or the internet.

“Anytime someone is putting ideas or words in your mouth, a line is getting crossed,” Olson said. ” It can happen when a tutor who is financially incentivized to make sure you get good grades goes too far, and they start telling you what to argue. That’s not a whole lot different from going on SparkNotes or ChatGPT and asking the question [or] finding somebody else’s answers and paraphrasing it as your own.”

If a student is caught receiving unauthorized aid on an assignment, their teacher compiles a report of the incident that is reviewed by the Honor Review Committee (HRC), whichdecides whether or not the student will be brought before the Honor Board. The HRC is made up of Church, both Head Prefects and one prefect from each grade. The Olson said taking a student to the Honor Board is a difficult process for both parties involved.

“I always feel bad when I [have] to take a student to the Honor Board because I know the emotional difficulty of that process is disproportionate to the weight of what may have occurred ,” Olson said. “There are senses of betrayal when it feels like it’s manipulative or when a student is just trying to get away with something. The hardest part is when you have a student who is insisting nothing is wrongwhen from a teaching standpoint, there’s something not clear, and you’re not getting a truthful answer.”

Harper Fogelson ’24 said the most common form of cheating is students hearing about what is on a test before taking it.

Cheating happens the most when there are different blocks of the same class on different days, so the blocks on odd days are always taking it first,” Fogelson said. “That just gives an inherent edge to everyone else who’s taking it later who chooses to cheat because they ask other people how it was or what was on it. [The problem] is hard for Harvard-Westlake, and I don’t know how they could fix that.”

Typically on assessments, students write down the Honor Pledge, a shortened version of the Honor Code that swears the student has not received unauthorized aid on the assignment. This has been a standard practice at the school since 2013. Fogelson said signing the Honor Pledge so often can make it seem insignificant.

“I don’t put as much thought into [writing the Honor Pledge] as other people do,” Fogelson said. “You sign it so often because you have a quiz or a test almost every day, so when you are writing ‘my name affirms my honor’ and [signing] it everyday, it becomes a bit monotonous, and you forget the purpose to it.”

Fogelson said finding out that others are cheating can be frustrating and demotivating for students who complete their work on their own.

“I know there are people who cheat in every class, but I try to not hear about it [and] just to keep to myself,” Fogelson said. “I take pride in my work ethic because I put a lot of work into school. When people cheat, it’s just discouraging, and it doesn’t make me want to work as hard because it feels like everyone else is [going to] do better than me because they’re cheating.”

Peter Jason • Nov 18, 2023 at 11:45 am

Terrific article. This should appear every year to remind us of how important the truth can be and why we use a system of honor to begin with. Certainly our government and press should be schooled in the merits of this article. Great job everybody!