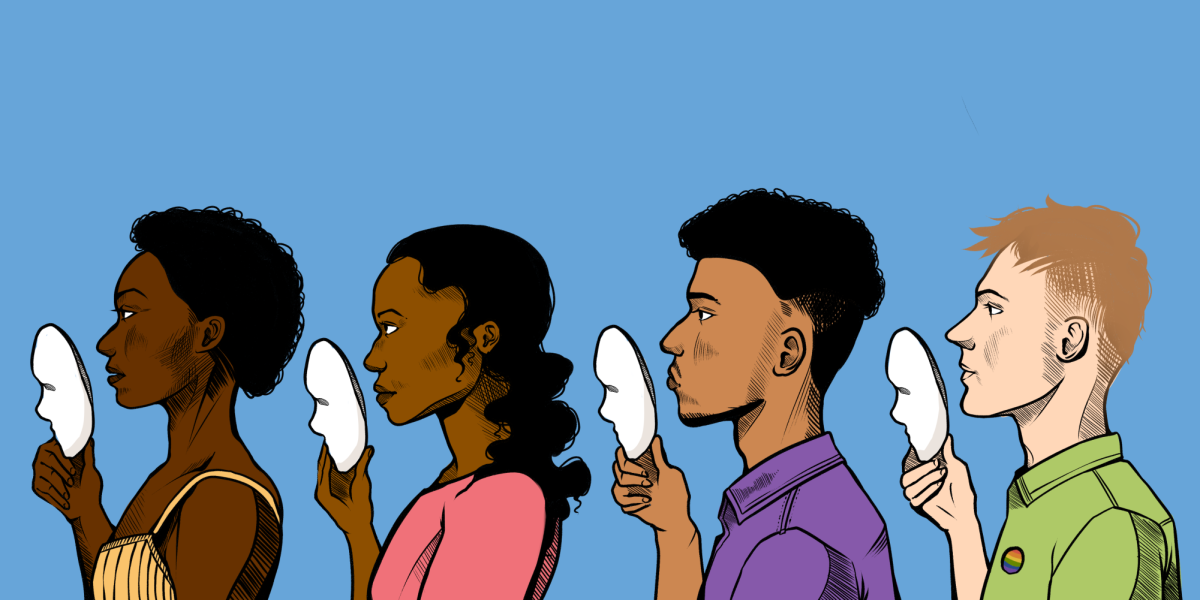

It is testing day for third graders in California. Micah Parr ’25 sits in a classroom full of students as he prepares to take the Educational Records Bureau (ERB) test. Before the exam begins, he fills out the personal information section of the test. Despite being part white, Asian and Black, Parr said he did not think twice about his answer to the question: “What is your race?” Parr said growing up, he never embraced the different parts of his identity.

“There [have] been times where I [didn’t] feel like part of one race at all,” Parr said. “When I was younger, because I was darker, I just thought of myself as Black. I did not see myself as Asian [or] white. I just saw myself as Black because that’s what I was told to see. When I filled out the standardized testing papers, we would only [select] one race. I would think, ‘Okay, I’m just Black.’”

The multiracial population in the U.S. has increased by 276% from nine million people in 2010 to 33.8 million people, 10.2% of the country’s population, in 2020, as per the latest census. At the school, 18% of the student body identifies as multiracial, according to Assistant Head of School for Community and Belonging Janine Jones.

For many in the school community, the holiday season gives them a chance to celebrate and spend more time with their families. However, these celebrations can offer a unique set of challenges for the multiracial population. Sarah Parmet ’25, who is part Korean and part white, grew up in Hong Kong, and as a result, is fluent in Mandarin but not Korean. Parmet said it can be difficult to connect with her grandparents and her Korean heritage because she feels more Chinese than Korean.

“My grandparents speak English, but there still is a barrier,” Parmet said. “It’s difficult because they wish I knew how to speak Korean, and I also wish I knew how to speak Korean. Then, I could better communicate with them. I feel disconnected from the Korean part of my heritage. In a way, I feel more Chinese than I feel Korean, even though I’m not Chinese.”

Similar to Parmet, Riyan Kadribegovic ’25, who is part Indian and part white, said being half Indian sometimes makes it difficult to connect with her Indian heritage.

“My grandparents and uncle on my mom’s side are all in India, so we generally go every other year,” Kadribegovic said. “Being half Indian makes it harder for me to connect with some full Indian people because sometimes I feel that I don’t know as much of the culture as they do, or that I’m not as involved as I could be.”

Kadribegovic said she feels pressure to conform to a different set of cultural standards depending on the side of the family she is with.

“Being mixed is interesting because people expect you to act a certain way when you’re with Indian people, and then people expect you to act a certain way with white people,” Kadribegovic said. “For me, since I’m racially ambiguous, people will tell me when I’m with my mom, I look exactly like her. Then, when I’m with my dad, people will say [I] look exactly like [my] dad. People expect me to act more white when I’m with my dad and more Indian when I’m with my mom.”

However, for others in the multiracial community, the holidays can be a time to form deeper connections with their family. Nilufer Mistry Sheasby ’24 said opening up to her family about her identity struggles relieved a lot of the disconnect that she felt.

“I’ve always been aware that my mom’s side of the family is fully Parsi and I’m mixed,” Mistry Sheasby said. “Two years ago, around the holidays, I decided to read them something that I wrote about being mixed. I’d been thinking about my identity and struggling with it for some time, but I never mentioned it because I didn’t think my family would really understand. I also didn’t want to bring something up have I was already worried was a point of separation or distinction between me and the people I loved. For me, after I expressed myself, any anxiety I felt about how this might change or alter my relationship with my family completely dissipated. What matters is that we care about each other and will always honor experiences that matter to any one of us, even if we don’t always understand or share them.”

Likewise, Parr said spending time with his family has helped him feel more connected to his identity.

“I used to not feel connected to my Japanese and Jamaican culture,” Parr said. “I’ve been slowly learning more and more about my cultures by connecting with my family and asking questions. That is how I’ve been able to grow and start to feel more in touch with my different cultures.”

Ava Hakakah ’25, who is part Persian and part white, said she noticed that there are a lot of cultural differences between her parents.

“Being mixed is really interesting, especially when you have divorced parents, because there are different cultures in different households,” Hakakah said. “At my dad’s household, especially because he’s Middle Eastern, he’s really family-oriented. [During] the holiday season, that [value] comes out, and it becomes a main priority in our household. We always have family over, and we’re always spending time with each other. On my mom’s side, even though we love our family, we’re not as close together, so that’s felt more around the holidays. My mom’s side doesn’t have the same kind of community that is prioritized in Middle Eastern culture.”

Beyond Mistry Sheasby’s parents’ ethnic differences, her dad is Catholic, and her mom is Zoroastrian. Mistry Sheasby said her family’s holiday celebrations honor a combination of different cultures and religions.

“I love that it is not as much religiously mixed as it is culturally mixed,” Mistry Sheasby said. “Even though Zoroastrians don’t celebrate Christmas, and my dad isn’t a super devout Catholic, we love celebrating. Usually, our traditions end up being a weird fusion. For example, my dad will make gingerbread cookies for one course, and my grandmother will make tandoori chicken for the other course.”

In addition to many students being multiracial, many also celebrate multiple winter holidays. For example, Hakakha has celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas, ever since her mom converted back to Catholicism. Since Hanukkah and Christmas aren’t determined by the same calendar, they do not always coincide. Hakakah said she appreciates being able to celebrate both when Hanukkah and Christmas overlap.

“The couple of times that one of the days of Hanukkah has fallen on Christmas, it’s been fun to celebrate both holidays at one time,” Hakakah said. “I spend the morning with my mom, opening gifts and listening to Christmas music. Then, I spend the evening with my dad, lighting the menorah and playing dreidel.”

Both Hanukkah and Christmas have been celebrated for over one thousand years with drastically different religious messages. Over time, both holidays have evolved to represent much broader messages. Hakakah said she enjoys celebrating both holidays because they spread a positive message and create more time with family.

“Both holidays have the same message,” Hakakah said. “For me, Christmas is about spreading the message of joy and kindness, and Hanukkah has been transformed to spread the same message of holiday joy and family togetherness. Both holidays allow me to spend more time with my family, and they’re both fun to celebrate.”

Kadribegovic said her family celebrates Christmas, despite following Zoroastrianism as opposed to any form of Christianity. She said she sees celebrating Christmas more as part of being an American rather than as part of a religion.

“Christmas is becoming more of a secular holiday,” Kadribegovic said. “It’s a national holiday. People get the day off, and it’s recognized as something prevalent in America, even though there isn’t a national religion. We feel like celebrating Christmas is more of an American thing to do rather than a Christian thing. Since both of my parents immigrated to America and are now American citizens, it felt like a thing that we had to do to show that we’re American.”

Mistry Sheasby said the holidays are more about the ideals behind them as opposed to the actual traditions in America.

“I love that my family has been able to take something that’s culturally American, and not really ours, and make it into a celebration of family,” Mistry Sheasby. “It’s reflective of how in this particular country, concrete traditions matter less than the aspirations and values behind them. Anyone, regardless of religious background or nationality, can celebrate the holidays in this country because it’s about caring for other people and love between families.”