At 13 years old, Elliot Kang ’16 imagined what it would be like to be the protagonist from his favorite show, “Dragon Ball Z.”

The latest episode in his series of superhero daydreams frequently interrupted his learning in math class.

“I wouldn’t get much done because I would be thinking about possibilities rather than what actually needs to be finished,” Kang said. “But you don’t really need to get anything done in middle school.”

Kang said he would daydream whenever he got bored, an experience shared by many students across the country. Similarly, Mady Schapiro ’16 daydreams every day in class because she is bored.

“I think I had my first actual daydream in the third grade on the swings at school,” Schapiro said. “I used to try and force myself to daydream in first grade because my friend would tell me about her daydreams, and I wanted to do the same.”

Daydreaming is often cast in a negative light, and kids who daydream are absent-minded “space cadets” who are often found with their heads in the clouds.

However, counselor and humanities teacher Luba Bek does not believe that is true.

“We need to turn off our consciousness every now and then,” Bek said. “Sometimes, it takes a little moment for us to recharge because we’re bombarded by millions of bits of information every second, and if we noticed everything, we wouldn’t be able to function.”

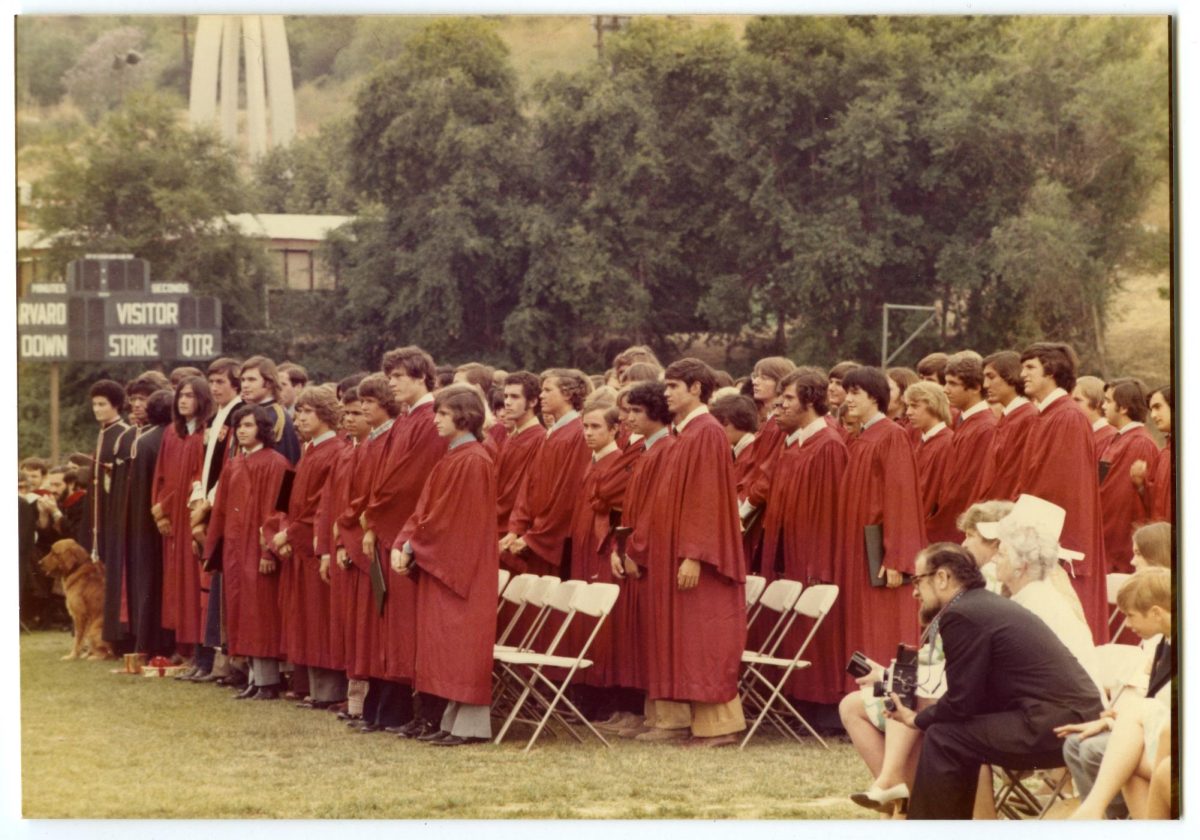

Although humans have been reported to spend around 50 percent of their waking lives in some state of mind-wandering (particularly daydreaming), according to a 2010 Harvard study by Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert, they also discovered that this mind-wandering contributes to higher levels of unhappiness.

“A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind,” Killingsworth and Gilbert wrote in the journal “Science” in November 2010. “The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost.”

This experience rings true to Schapiro, who said that as she continues to daydream, her dreams have become more negative.

“The daydreams [became] more [about] dreams of failing and being an outcast and unwanted by society,” Schapiro said.

However, another theory of daydreaming was suggested by Scott Barry Kaufman, Scientific Director of the Imagination Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. Kaufman’s research suggests that daydreaming helps people start to pursue goals that carry personal meaning, which “fosters creativity” and results in increased self-awareness.

“Much of the same awareness and goal-setting that is pursued in schools is actually encouraged by daydreaming, according to this theory,” said Ali Cram, a clinician at University of Southern California’s Psychology Services.

As a result, Cram said Kaufman’s study attempts to prove how daydreaming can often lead to sudden connections and deep insights due to an ability to recall information despite facing distraction.

This theory, however, does not fit Bek’s experience with the Harvard-Westlake community.

“From what I know, [daydreaming] helps you catch a break in this huge informational flow that is out there,” Bek said. “I don’t think it ever resolves an issue or ever makes somebody plan something because when you daydream, you’re not quite consciously there. [With] dreams, maybe, but not daydreams.”

This observation is supported by Kang, who finds daydreaming useless in his everyday life and has stopped daydreaming with his transition to high school.

“I don’t have time now,” Kang said. “I’m stuck in the now, not in a fantasy world anymore.”

Schapiro has continued to daydream in high school. She said that it has no effect on her academics or extracurriculars and allows her to “escape stress” while in class.

According to Kaufman’s book, “Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined,” when students taking standardized tests allow their minds to wander and make personal connections to their lives, they are able to perform better on exams and in school.

However, Cram said the difficulty with daydreaming is maintaining its balance with mindfulness. Conscious awareness has been linked to improved knowledge acquisition, reduced stress and higher levels of compassion.

“Mindfulness is what you hear a lot of schools emphasizing,” Cram said. “These practices are usually related to being in the here-and-now, paying attention, focusing only on what’s right in front of you. And even though it’s always smart to wonder if you should be living in the moment, always being in this state can cause a kid to miss out on important connections between their inner thoughts and the outside world.”

However, to Bek, a teacher’s role in maintaining student attention does not lie with the student, but with the teacher.

“Things distract you. When they distract you, you stop paying attention, you start daydreaming,” Bek said. “Teachers can encourage kids to pay more attention, but I think ultimately, it’s the teacher’s job to make sure that there is something to pay attention to.”

The creativity that is emphasized and encouraged in school curricula, such as increased student discussion and self-expression through art or writing classes, is said to be connected to the creativity in daydreaming.

“The latest research on imagination and creativity shows that if we’re always in the moment, we’re going to miss out on important connections between our own inner mind-wandering thoughts and the outside world,” Kaufman told the Huffington Post in 2013. “Creativity lies in that intersection between our outer world and our inner world.”

However, Bek has experienced different daydreaming patterns in students.

“I don’t think people who daydream in class think about anything large, […] but the vast majority [of people find] sometimes something really big that’s bothering them [will distract them, and] you drift off and think, ‘oh my god, my mom is sick, my paper is due.’ But most people think of about something immediate,’” Bek said.

However, it is difficult to find definite research on daydreaming, Bek said, because, “it’s self-reported, and…as human beings, we have this innate desire to be liked, so we don’t necessarily report the truth. I’m not saying we’re lying, but we’re embellishing a little bit.”