Superhero movies are always the same. Powerless, struggling characters are in trouble and only the superhero has the ability to save them. The protagonist defeats the villain, saves the helpless characters and maintains good in the world.

In reality, this is not where the movie ends. Our superheroes are the white saviors, and though they may not wear capes, they do envision it to be their duty to spread their culture and wisdom to the rest of the world.

The white savior complex is a term encapsulating the cultural practice of Western people traveling to foreign areas with the notion that they can and will save entire communities from all problems, even those unfamiliar to Westerners themselves.There might be good intentions behind such endeavors, but we must ask ourselves: at what cost are we doing this, and for whose benefit? Promoting which stereotypes? Playing into what narrative?

The satirical Instagram account @barbiesavior documents a Barbie doll on “voluntourism” missions in Africa, posing with children in run-down classrooms and posting photos with captions like, “This little one’s greatest joy in all her life is sitting on my lap and drinking Coca Cola!” or “It’s so sad that they don’t have enough trained teachers here. I’m not trained either, but I’m from the West.”

The story often goes something like this: “We want to travel to far-off, dreamily exoticized lands and bring the light of truth to the people there,” Anne Theriault writes in a HuffPost article. “Like the missionaries, we assume that we will bring wonderful, life-changing revelations to these people. We imagine ourselves standing before a crowd of dark-skinned women, their mouths little round Os of amazement.”

We are incredibly privileged to have access to higher education and the range of opportunities our community provides, but it is easy, as a result, to cultivate a false sense of superiority and self-righteousness from these experiences. This creates an underlying mentality that there is less suffering and less oppression as a whole, and as a result, any one of us can help those that are oppressed. Theriault warns of the consequences of this perspective: “When we take a closer look at these statements, however, their core message becomes clear: our culture is better. We are more enlightened, more rational, and more civilized. Other cultures should strive harder to be more like us.”

The concept of the “white man’s burden” as justification for Western imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th century is mirrored in many of our foreign policies and actions today. The idea of the Western savior figure is reinforced through media, from classic novels and films (To Kill a Mockingbird, Lincoln, the Indiana Jones series), to foreign policy, which perpetuates the sense of a more superior and accomplished West that furthers the assumption that we are more qualified to aid those who are considered less capable.

2015 CNN Hero of the Year Maggie Doyne exemplifies this theme’s pervasion into volunteer work. Although building a school, women’s center and children’s home in Nepal is extremely commendable, her photos easily provide a visual and perpetuate the stereotype for the “white savior”: a lone, Western figure surrounded by darker-skinned, beaming children. Immediately, the children are reduced to an exhibition-like representation of oppression, helpless and dependent upon the volunteer.

A side-effect to the age of viral TED Talks and social media activism is what Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole calls the “banality of sentimentality,” claiming that society’s normalization of sentimental acts causes those same actions.

This perception results in the belief that “the world is nothing but a problem to be solved by enthusiasm,” Cole said in a tweet. The issue with the drive behind actions guided under the myth, Cole writes, is that it does not come from a desire for justice but from the need to have “a big emotional experience that validates privilege.”

Before we educate others, we must educate ourselves. We cannot rely on our background in living in our “model” society and use it as the standard for the rest of the world. We must consider if people in other societies truly want to be “saved,” and if so, how best we can constructively help.

“There is much more to good work than making a difference,” Cole writes. “There is the principle of first do no harm. There is the idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them.”

Uninformed but well-meaning actions easily backfire and cause more harm than good. In 2013, the radical feminist group FEMEN, originally created in protest of the Ukrainian sex industry, organized International Topless Jihad Day, a topless protest in front of mosques “on behalf of Muslim women.” Activists inflamed Muslim stereotypes with slogans scrawled in pen on their chests, reducing women and their experience to their headscarf and clothing–an image of oppression to many Westerners.

Many Muslim women struck back, forming a Facebook group called “Muslim Women Against FEMEN” with pictures of them holding signs that read “I’m a Muslim feminist…FEMEN does not speak for Muslims or feminists,” “Nudity does not liberate me and I do not need saving” and “I don’t appreciate being used to reinforce Western imperialism. You don’t represent me.”

Intended to empower Muslim women, the protest only marginalized them. Even something small as texting 90099 to donate $10 to the Red Cross should be done with what Cole calls “awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.”

Falling into the savior mindset reinforces a cycle of superiority. The image of non-Western oppression promotes “voluntourism,” which in turn furthers the perception of inferiority. As a result, these acts become more about ourselves and our privilege than those we really are trying to help. Instead of perpetuating this superiority myth, we must really understand the ramifications of our actions; instead of raising ourselves on a pedestal, we must empower and amplify the voices of others.

There are atrocious acts occurring internationally that do need attention, and humanitarian aid is absolutely essential and should be encouraged, but we must redefine our own role in providing aid beyond simply mirroring our own culture. The emphasis on continuous and sustainable actions and results ought to be a major prerequisite of non-white savior work.

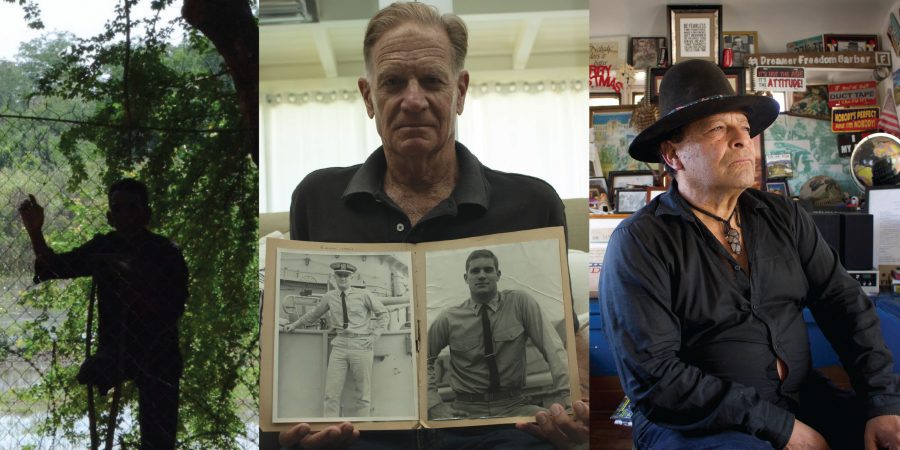

Domestically, Robert Egger demonstrates this work through L.A. Kitchen, a social enterprise committed to reducing local food waste, combating unemployment and aiding seniors in poverty. The culinary training program offers foster care youth and parolees a means to support themselves, which in turn combats issues of homelessness and recidivism, while fulfilling its main goal of feeding the food-insecure elderly. This leads to positive effects such as a decreased dependency on medical care and a reduced financial burden on society.

Egger brings an energy that breaks through pre-existing notions that low-income seniors can’t be well-fed or that parolees won’t make good employees. His favorite moments, he says, are when these transformations occur, when “someone who’s like fifty, [is] excited because this is the first paycheck they’ve ever gotten in their life.”

He doesn’t establish himself as a savior figure. Instead, he works among the community and creates opportunities for disadvantaged people to reinvent themselves and the status quo. Egger understands that problems cannot be solved with enthusiasm alone and stresses the importance of “marrying a social mission with proven, business-driven strategies,” fortifying L.A. Kitchen’s sustainability by seeking the advice of restaurant founders, legal advisors and community leaders.

“I just think that everyone and everything has value,” Egger said. “I would like to see my project redefine the world of elders, parolees, foster youth [and] culinary experts in American society.”

Egger is able to work with his community to challenge the traditional narrative of what is accessible to whom. We should take this concept to heart when we do volunteer abroad and challenge the savior, “superhero” structure by empowering others to wear their own capes–or better yet, not wear one at all.