Jane’s* ’18 head was pounding as she made her way into the kitchen in the afternoon. She was about to take her first a bite of food that day when her dad came into the room, yelling that she needed to keep her annual promise to God.

Jane was fasting for Yom Kippur, a Jewish holiday in which Jews go without food or water for 24 hours to facilitate self-reflection. Last year was the first time Jane broke the fast before the day was over.

“My health was preventing me from doing it, and I always feel like my health comes first before anything,” she said. “My dad definitely was not on the same page as me. He thought the fast and the Jewish holidays come before anything else.”

Although she usually fasts for Yom Kippur, Jane attributes her Jewish identity to the culture rather than the belief system. She said she does not regularly go to temple or pray.

Jane’s dad, however, is much more religious and spiritual, she said.

In addition to placing great value on Jewish practices, her dad meditates frequently and tries to persuade Jane to participate in spiritual exercises. Jane said she gets frustrated at her dad’s suggestion that she needs spirituality in order to better herself.

“I don’t feel like I need to do anything more to be in touch with myself,” Jane said. “Sometimes [my dad] thinks I do, and that’s a little offensive. I feel like I’m pretty comfortable in my own skin without doing that.”

25 percent of people 18 to 30 years old are unaffiliated with a religion—agnostic, atheist, or “nothing in particular”—versus the 14% of all adults over 30 years unaffiliated with a religion, according to the Pew Research Center.

Grace Swift ’19 is part of the 59% of students on campus who said they feel less religious than their parents, according to a Panorama poll of 328 students. Like 34 percent of students who responded to the poll, she identifies as an atheist.

Swift said she started considering herself an atheist in seventh grade. Initially, it served as a mechanism to defy her mom, she said. Looking back, however, Swift said she never truly identified with Christian beliefs.

When Swift expressed herself as an atheist to her parents, it created significant tension in her house, she said.

“It almost felt like ‘coming out’ to my parents,” Swift said.

Swift’s mom was ardently unaccepting of her atheist convictions, she said. Swift said her mom now forces her to participate in church monthly as an acolyte.

In contrast, Anita Anand ’19 said that while her mom is more religious than she is, she accepts Anand’s agnostic beliefs. Both of Anand’s parents mainly care that she receives the core values and culture from Hinduism.

Anand said that she connects to her Hindu culture through Indian dancing. The dances she performs portray religious stories and texts.

Similar to Anand, Swift said there are appealing characteristics of the Episcopal Church that she is able to separate from belief in God.

Swift said she has been going to church since she was a baby and has grown up enjoying its structure.

“It’s less about God for me than it is about routine,” Swift said.

She also said she values the morals that the church instills in its congregation. Swift said she would not feel comfortable being involved in another sect of Christianity or in another religion that does not give considerable weight to ethics.

“This church is a lot less about religious dogma and a lot more of just trying to teach people how to be good people, which I appreciate,” Swift said.

Swift said she wonders about the number of people in her church who are there to practice their religious beliefs versus the number of people who are there to benefit from the church’s moral lessons.

Zeke* ’19, like Swift, values religion for its moral guidelines rather than for a belief in a divine being.

Zeke’s parents saw religion as a crucial aspect of growing up, Zeke said, and sent him to a religious elementary and middle school.

While Zeke said his parents have a stronger belief in a divine being than he does, they also believe the most beneficial aspect of religion is its moral principles.

“[My parents] have definitely introduced me to this world of religion, but I feel like my beliefs have been shaped mainly by my experiences,” Zeke said.

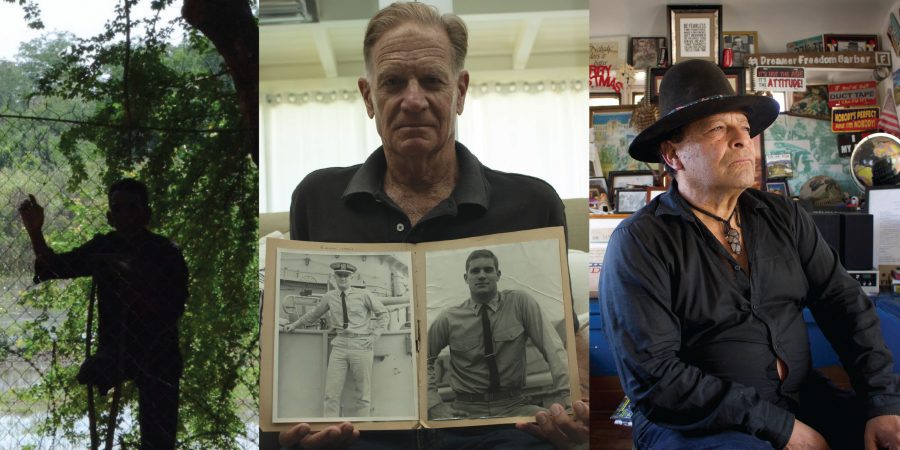

Zeke said he started grappling with the idea of a divine being after his dad was diagnosed with lymphoma cancer and two family-friends died of breast cancer.

“I was wondering ‘Why are all these bad things happening in my life?’” Zeke said. “That was a time of questioning. But, I do think that everything happens for one reason or another.”

As a kid, Zeke and his family went to church on a regular basis. Now, they only go for Christmas and Easter. Zeke said his family no longer has the time to practice religion, which, in turn, has led to them becoming less religious.

Julia Maccary ’19 is another student who said she and her family have become much less religious over the past few years. However, Maccary attributes this to personal tragedy.

Maccary was raised in a Catholic home. She was baptized, went to Sunday school and took her first communion.

“It was a family thing—every Easter, every Christmas—to go to church and have a big meal after,” Maccary said. “I was raised like that. That was my culture.”

Her parents have now stopped taking her family to church, Maccary said. After her grandfather passed away, she said her parents lost their dedication to the church.

“My parents are both very pragmatic people, and I think they probably wanted to believe in some higher power,” Maccary said. “I think it’s very comforting to think that, but I think they both sort of knew.”

Now, Maccary said she and her sister consider themselves atheists. They started questioning the existence of God at the same time, Maccary said.

“I think we sort of fed off of each other,” Maccary said.

After Maccary started to question God, she said she also questioned why people ascribed to religion in general.

“I think a lot of it comes from people’s desire to be comforted by some explanation for what’s happening,” Maccary said. “For example, ‘Why does this tragedy have to happen? Oh, because some higher power has made it happen.’ I also felt like it was a way for people to control their destiny in some way to think, ‘If I do all these great things in my life, it can pay off in the afterlife.’ I like to think there is a place after earth, but I don’t know if I believe that.”

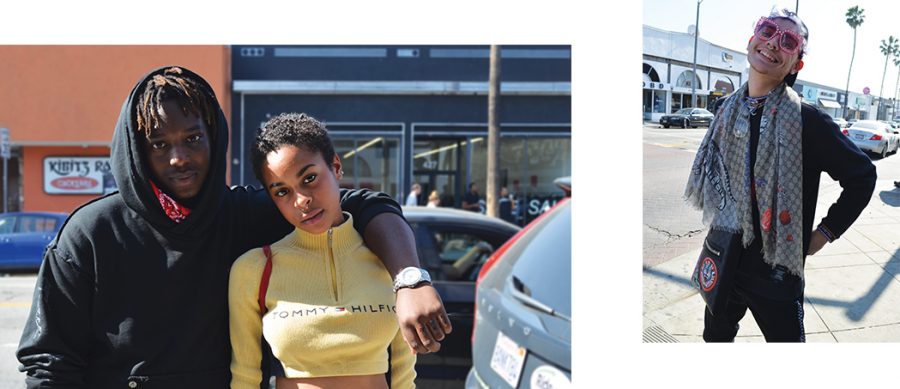

Maccary said her beliefs were shaped by growing up in Los Angeles. Both her liberal parents and community allowed her the freedom to explore her relationship with religion, she said.

“If I had lived in a place where being atheist or agnostic wasn’t common at all, it probably wouldn’t have occurred to me,” Maccary said. “I feel like my liberal environment in LA has allowed me, early on, to find what I think is true.”

In a Panorama poll of 271 students, 57 percent said that the liberal climate in Los Angeles has influenced their religiosity.

Both Anand and Swift said they have found that their peers do not hold strong convictions in any particular religion or faith.

“I think it’s more and more common to get away from the structure of a religion and just lean towards more of a free, open idea of, ‘well, there might be somebody out there, but I don’t really know,’—more of an agnostic take on the world,” Swift said. “I feel like less people are atheist or Catholic or some religion with really strict rules.”

Upper school Chaplain J. Young said he thinks Harvard-Westlake unintentionally attracts families who are less religious.

“I think that if you are a family in Los Angeles and you are sending your kid to a private school, and it’s important to you for that school to have a strong religious base, you’re going to be looking at Loyola, or a Jewish day school or Oaks Christian,” Young said. “I do think because we don’t fall into those categories as being uber religious, by definition, we end up attracting families who are less religious. Not because we’re intending to, but kind of a side effect of what the other schools are offering.”

Anand expressed her appreciation for the school’s acceptance of diverse religious beliefs, including those who don’t strongly identify with a religion.

“It’s always nice to have people with different perspectives and beliefs coming together in unity,” Anand said. “I like that my friends — and my parents—don’t judge me for not believing in God.”

*Names have been changed.