Blue, red and white lights flashed in front of Xenia Bernal ’19, blurred by the tears that swelled in her eyes.

Bernal, a first generation Mexican-American, was in the backseat of a car driving through the streets of Los Angeles with two family members, one of whom was undocumented in the passenger seat.

Two police officers came to the window of her car, which was pulled over on the side of the road. One was kind to Bernal and her family members — the “good cop.” The other was aggressive.

“I remember just sitting in the back seat and bawling and crying and being so scared,” Bernal said. “I felt like I was about to be ripped away from this family member, and I was scared. There’s really no other way to put it.

“After rolling through a stop sign, police pulled the family over which launched Bernal into a state of fear and panic, she said.

“It was paralyzing because I didn’t feel like I could talk or say anything,” Bernal said. “Even with the supposed education and opportunity that I have, what does that matter when I don’t have my family anymore?”

Although the family left without incident, as it was only a minor traffic violation, the experience exemplified the angst that Bernal said she feels when thinking about her family members who are undocumented, especially in today’s political climate, when anti-immigrant rhetoric feels prevalent.

“I wouldn’t wish the feeling that you sometimes have to carry on anyone, not on my worst enemy,” Bernal said. “It’s very isolating. It makes you feel like at any moment you can be alone.”

With the introduction of government policies, such as the travel ban and zero tolerance policy that are meant to curtail immigration to the country and are filled with anti-immigration sentiments, students like Bernal say they feel unsafe and uncertain.

Despite the fact that 75 percent of people in the US say that they support immigration, according to a June 2018 Gallup poll, 31 percent of 326 respondents to a Chronicle poll said they feel there is a growing anti-immigration sentiment in the country.

One student, Faramarz Nia ’21, whose parents immigrated to the U.S. from Iran and whose cousins from Iran are unable to study in the country due to the travel ban, said he was disappointed when he heard the rhetoric being used towards immigrants.

Sophia Nuñez ’20 experienced such rhetoric firsthand after commenting on an Instagram post saying that people should not stereotype and villainize immigrants, another user commented back saying, “It’s not like your family came here legally.”

Nuñez, who is of Mexican heritage and whose family has lived in America for many generations, said she immediately started to cry after seeing the comment, overwhelmed by the hostility and offended by the stereotyping.

“The color of my skin doesn’t change that I was born here, and the color of my skin doesn’t mean that you get to make assumptions like that, or that any assumptions that you make are inherently bad,” Nuñez said.

Of the students who said they feel there is a growing anti-immigration sentiment in the country, 18 percent said that they feel personally affected by it.

“Basically everyone in the US is an immigrant,” Nia said. “We’re the land of immigrants. I think it’s kind of ironic that as soon as somebody comes inside we all of a sudden close the doors to the people trying to get in, even though over a hundred years ago someone else did the same thing, whether or not they wanted to let them in.”

Upon learning that the Supreme Court upheld the travel ban, which bars people from seven countries from entering the US, Nia couldn’t help but draw parallels to other periods he had learned about in American history.

“It’s so much easier for people to generalize and exclude a whole group of people,” Nia said about the travel ban. “It’s the same thing that happens in history.”

From the first wave of Irish and German immigrants to the US in the 1840s to Eastern European immigrants in the late 1800s to immigrants today, history teacher Francine Werner said the words used when addressing immigrants have not changed.

“You can find laws in Congress proposed in 1908, and the language is the same,” Werner said. “It’s the same hostility, and usually it’s in times of economic distress.”

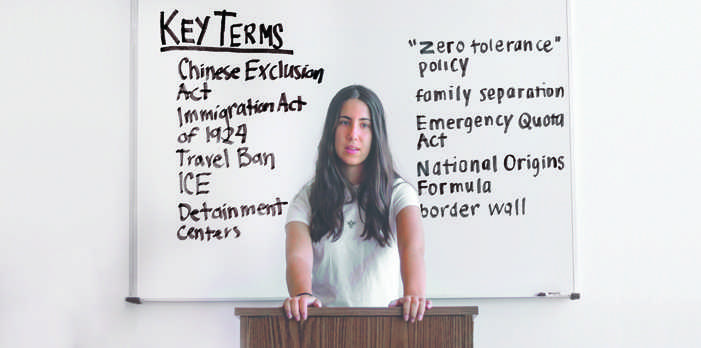

To bring up this conversation on the first day of school, Werner showed her United States History classes a video of MSNBC reporter Rachel Maddow, who broke down when reporting on the separation of families at the US-Mexico border in June.

“She kept saying ‘this is not who we are, this is not who we are,’ and I was thinking, ‘yeah, it is,’” Werner said.

One difference between the anti-immigration sentiment today and those in other periods of history that Werner pointed to is the pushback from those who believe immigrants should be welcomed into the country.

“There are pockets of people in this country where it’s like they’ve been given license to be anti-immigrant,”Werner said. “But, there are a lot of other people responding by saying ‘what can we do?’”

Following recent controversial immigration policies, protesters lined streets demanding to bring families back together and lawyers flocked to airports and border cities to offer their services.

As a co-president of the Human Rights Watch Student Task Force, Catherine Crouch ’19 has been working to spread awareness about immigrant rights, specifically those of children protected under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), for the past year by hosting speakers and facilitating discussions on campus.

“It’s been really upsetting seeing the blatant rudeness toward immigrants, the total ignorance toward their situation and the lack of any solutions,” Crouch said. “Any kind of effort to think about people other than yourself is just really gratifying, and also makes you more in touch with the world. We have so much, so we should use that to help others.”

Whether the anti-immigrant rhetoric has emboldened groups to echo similar sentiments or motivated groups to work to help immigrants, the issue of immigration was one of the most important issues to young first time voters this summer, Andrea Yagher ’20, who worked with a voter registration organization called Our First Vote extensively, said.

As the issue of immigration becomes increasingly more visible, Bernal said she hopes students will take the time to not only inform themselves about the issue but also to take action.

With a place for conversations about immigration in the classroom, Bernal said she hopes students will use their knowledge to create change outside of the classroom by calling their elected officials.

Empowered by the opportunities that come with her education, Bernal said that she feels a responsibility to speak up and help those that need to be heard.

Coming from a Latin-American family that values tradition and togetherness, Bernal said the thought of some of her extended family members who are undocumented being forced to leave the country motivates her to work to uplift those who do not have a voice in the conversation.

“Just imagine all of [your family traditions] being gone — we don’t have any Christmases, we don’t have any Thanksgivings, we don’t have anything anymore,” Bernal said. “What else can you say? That’s my whole life. My whole life can be taken away. And the only thing I could really do is protest, but people forget about that as quickly as it comes. It’s a terrifying thing.”