The Fight Against Fentanyl

Students and experts reflect on the growing relevance and threat of the fentanyl epidemic in America.

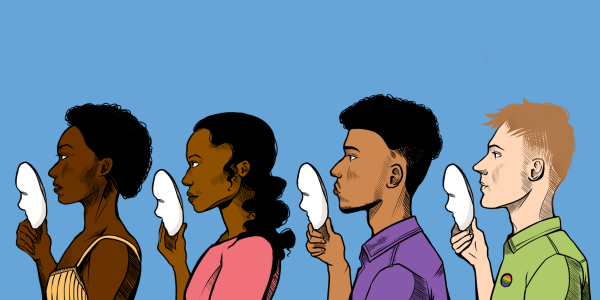

Illustration by Alexa Druyanoff and Fallon Dern

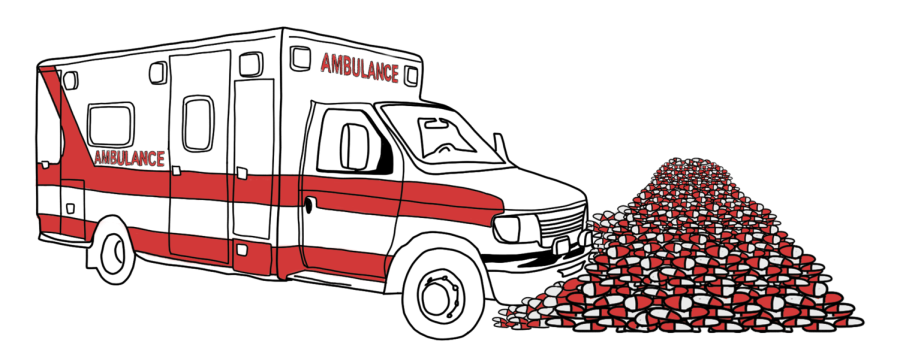

According to the DEA, more than 25 % of counterfeit pills are laced with fentanyl.

January 21, 2022

On Sept. 25, tucked away in Mandeville Canyon, a party raged: In the backyard of a large white house, kids packed tightly together, laughing and screaming joyously. Despite their jovial attitudes, most of them were total strangers to each other, with one of their only similarities being the Instagram account they followed to be added to the event’s guest list. Lights flashed too bright and music played too loud, echoing across the surrounding hills and drowning out the sound of an oncoming ambulance’s siren, Nora*, a student who attended the party said.

It all came to a stop, though, when the ambulance appeared in front of the home. Nora said kids scattered, scrambling over fences, running down the street—anything possible to distance themselves from the party and the paramedics and officials putting an end to it. However, two remaining attendees would require the help of those paramedics to leave; one of them suffered alcohol poisoning, while the other had ingested and overdosed on a fentanyl-laced narcotic.

Students reflect on the party where an overdose occurred

Nora said the event felt more uncomfortable than others she attended in the past, even before the overdose occurred she left early in the night.

“It definitely didn’t feel like most parties, it felt like something was off,” Nora said. “My friends and I felt safe, but we’d felt safer [at other gatherings]”

Nora said the party’s location was extremely inconvenient, and ultimately exacerbated the panic that arose after the overdose.

“When we were leaving, it was impossible to get an Uber,” Nora said. “There was no service, and [the Uber] took 20 minutes to get up to us, and all of this was an hour before everything even happened. So I can’t even imagine what it was like when [that girl] overdosed.”

Toby*, a Crossroads School student at the party who witnessed the event firsthand, said when he saw one of the victims, he immediately knew something had gone wrong.

“I see this girl lying on the grass lawn, motionless, with five or six people around [her], clearly stressed and worried for someone who seemed to be their friend,” Toby* said. “I’ve known people in the past who have [overdosed] on fentanyl, so my first thought was maybe it was that.”

Toby said there was immediate unrest as rumors of the unconscious girl spread throughout the party.

“People were saying, ‘Oh, she’s dead. They’re giving her CPR. The ambulance’s coming and the cops are arresting us, so everyone leave,’” Toby said. “I knew she was alive, but it seemed like everyone was going around and saying she wasn’t.”

Toby said although he did not personally know the girl who overdosed, and the experience did not directly affect him, the incident changed his perspective on fentanyl.

“It became more real,” Toby said. “You see stuff like this in movies and [other media] but it doesn’t actually happen. But it happened.”

Toby and Nora* said they have seen the atmosphere surrounding parties and drugs change since that night in September.

“I’ve been to a party since and the security has definitely been different, and there have been parents at every one of them,” Toby said.

“I told my mom about it,” Nora said. “Now every time I go [to a party], she says, ‘never take anything from anyone, don’t even take a granola bar, because you really don’t know anymore.’ And I totally understand.”

Toby said the party made him realize fentanyl should be something on everyone’s radar, even if it can seem like a distant threat.

“It would be delusional to say it’s not something to be worried about,” Toby said. “You only ever really hear stories about it, but it’s really messed up stuff.”

This overdose, which was subsequently featured in a Hollywood Reporter article, is merely one isolated event in a mass surge of fentanyl-related incidents across the country.

Certified Pediatrician shares the history of fentanyl

In recent years fentanyl has rapidly become a leading cause of death in both adults and teens, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fentanyl has caused the overdose of numerous celebrities, leading to the deaths of Mac Miller, Lil Peep and Prince, among others.

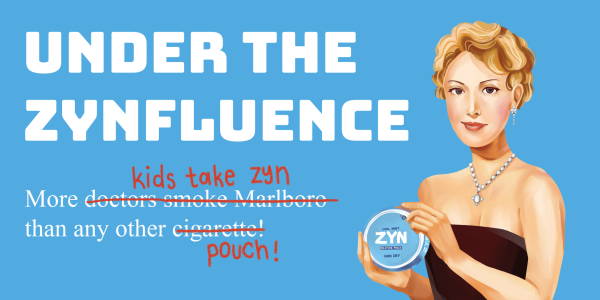

According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), over 25% of counterfeit pills are laced with fentanyl. Becky Mandel, a board-certified pediatrician and mother of a Marlborough student said the drug originated as a rare medical supplement.

“It’s 80% stronger than morphine,” Mandel said. “It’s a really powerful drug used for chronic pain associated with cancer. It’s not, for instance, medicine I would prescribe as part of my pediatric practice, and it would be so unusual for parents to have it.”

Despite its medical rarity, Mandel said the counterfeit production of fentanyl is alarmingly fast and widespread.

“It’s easy to make, and it’s cheap to make,” Mandel said. “[Fentanyl is cut into drugs] the same way, for instance, cocaine is laced with different substances to reduce the potency and make more product,”

Mandel said this method of manufacturing makes pills or other drugs highly dangerous, regardless of the context.

“Everything can be counterfeited,” Mandel said. “So at this point, kids need to know that nothing is considered safe. Nothing is considered okay.”

Juli Shamash discusses counteractive measures toward the drug

In a recent parent meeting, the school recruited Juli Shamash, co-founder of Moms Against Drugs, to share her unique perspective on the fentanyl epidemic and alert parents to the dangers of the drug. Shamash founded the organization after losing her son to a fentanyl overdose in 2018 and now spends much of her time educating groups about the drug’s dangers.

“We do awareness events in both [Los Angeles and Las Vegas], plus we help other grieving moms organize events in other states,” Shamash said. “I just got a sponsor for a law that will be called Tyler’s Law, [which] makes it mandatory for emergency rooms to do a fentanyl test whenever anyone is brought in for a suspected overdose.”

Shamash said events like these are necessary because actively stopping the spread of fentanyl is impossible and great amounts of damage have already been done.

“There is already enough fentanyl in our country to kill everyone here,” Shamash said. “It is too profitable for the cartels to stop making and importing fentanyl. Our only chance at beating this epidemic is through education.”

Shamash said she feels the fight against the drug is insufficient, which she said makes her activism all the more important.

“I do not think a good enough job is being done to spread awareness,” said Shamash. “I think the health department should be doing radio ads, billboards and blast it all over social media just like they do about getting vaccinated.”

Student’s share their level of knowledge surrounding fentanyl

Naalah Cohen ’23 said she knows little about the drug and said she rarely has conversations about it.

“I’ve mostly only heard about it from [HBO television series] ‘Euphoria,’” Cohen said. “I’ve never really talked about it with parents [or] teachers, [which is] really interesting.”

Nick Guagliano ’23 said he, too, rarely engages in education about the drug.

“I only talked to my parents about it one time when [the mom of] a family friend unknowingly took fentanyl in a lethal dose,” Guagliano said.

Shamash said she has seen the effects of this inadequate fentanyl education firsthand, both in her personal life and in the greater Los Angeles community.

“Three years ago, when my son died, he was the first young person that most people in West LA, including myself, knew, who died from fentanyl,” Shamash said. “Now, I think it would be difficult to find someone who doesn’t at least know one person who has died of an overdose.”

Shamash’s campaign against the drug hinges largely on mental health, which she said is the primary reason for victims attempting to acquire counterfeit drugs.

“If you are feeling anxious, depressed or even just have a headache, and a friend says, ‘Try this pill, it will make you feel better,’ you have to have that voice in the back of your head saying, it might be fentanyl,” Shamash said. “I know kids like to experiment, but you no longer have that luxury.”

Stella Glazer ’23 said she has seen friends ignore Shamash’s advice and turn to narcotics while under mental pressure.

“A couple of my friends have had hard times with their family and school and stuff, and so they were introduced to [drugs],” said Glazer. “It made them numb to the pain but it didn’t make them happier.”

Glazer said she has discouraged her friends from engaging with drugs.

“I was really worried for them, and I talked to them and told them that’s really not the way to fix your problems,” said Glazer. “I told them they should find support systems to talk to—friends, counselors or whatever they have, instead of [endangering] themselves like that.”

In her talk with school parents, Shamash said she was concerned for the greater school community.

“Fentanyl has been found in cocaine, pills, meth, heroin and even marijuana, [so] as far as how soon it will affect someone in your community, it is probably going to be sooner than you think,” Shamash said. “On average, I get one text or phone call a month from someone asking if I can talk to another parent who recently lost their child [to] fentanyl.”

Still, Shamash said she sees the school’s willingness to educate its community on the drug as a source of optimism.

“The school seems to be doing a really good job of educating the parents and the students about the dangers of fentanyl-laced drugs,” Shamash said. “Hopefully, this knowledge will keep the students safe.”

Both Mandel and Shamash said the role of parents is paramount in preventing fentanyl-related incidents.

“Parents need to start talking to their kids about fentanyl-laced drugs, from when they are in middle school,” Shamash said. “There should be no stigma in speaking about drugs or addiction.”

Mandel said she agreed with Shamash and said communication is beneficial communication in preventing drug exposure.

“It’s always just about talking to kids, having open lines of communication,” Mandel said. “Then you’re able to start the conversation with kids and say, this seems really scary. I want you to know about this.”

*Names have been changed