Highly Recommended

Teachers reflect on their experiences writing college recommendations

August 25, 2022

Jocelyn Medawar walks through her recommendation writing process

Every morning during the final weeks of summer, Upper School English Teacher Jocelyn Medawar wakes up at 6 a.m. to make herself a cup of black coffee and scrambled egg whites. She does not bother to brush her hair or change out of her pajamas before sitting down at her kitchen table. Surrounded by piles of papers and notes, she will not leave her chair until she has written at least two college recommendation letters for her students.

Later in the morning, Medawar is joined by her husband, fellow Upper School English Teacher Jeremy Michaelson. Together, they write on their laptops and sometimes compare sentences to ensure they are making their points perfectly.

Throughout the summer and fall, Medawar and Michaelson write between 50 to 60 letters, part of the school’s recommendation process that supports nearly 300 seniors applying to college. Medawar and Michaelson are known for being two of the school’s most sought-after letter writers according to Upper School Dean Sharon Cuseo .

They said this job was an important part of their relationship: they first socialized outside of school more than 20 years ago at the nearby Le Pain Quotidien to celebrate finishing their recommendation letters.

Since Medawar began working at the school in 1995, she says she has written around 1,000 letters, and since he joined in 1997, Michaelson said he has written around 700.

“I do not write novels,” Medawar said. “I do not write textbooks. I do not write criticism. I write recommendations. I take pleasure in a phrase that feels really satisfying or when I feel like I captured a student with the perfect words. There really is that moment of doing a fist pump when you feel like you got it right, and if I do not feel I got it right, I will tinker all the way up until I [submit it].”

Medawar and Michaelson’s morning ritual is repeated in various forms over the summer and fall as the school’s deans and faculty write a total of 1,000 unique letters of recommendation. Around 90 members of the faculty submitted letters for the past year’s graduating class, with many college applications requiring one letter from the school and at least two from teachers.

Administrators discuss how recommendations effect and expand student-teacher relationships

Before becoming Head of Upper School, Beth Slattery was a dean and later Upper School Deans Department Head. She said dean letters are supposed to offer holistic insight into each student’s identity.

“Deans benefit from having a multi-year relationship [with a student],” Slattery said. “35 letters is a lot, and you want them all to be robust and to capture the kids. You feel a big responsibility to make sure that they fully convey the school’s support. They are important, although not the most important thing in the college process.”

Cuseo has written thousands of letters of recommendation since she started working at the school in 1995. She said her goal with every letter is to offer a perspective about her students that goes beyond grades and test scores.

“The most effective letters of recommendation, both from teachers and the deans, help the student come alive to the reader and come off the page,” Cuseo said. “If [colleges] do not get a sense of the person, it is just harder for their whole application to make sense.”

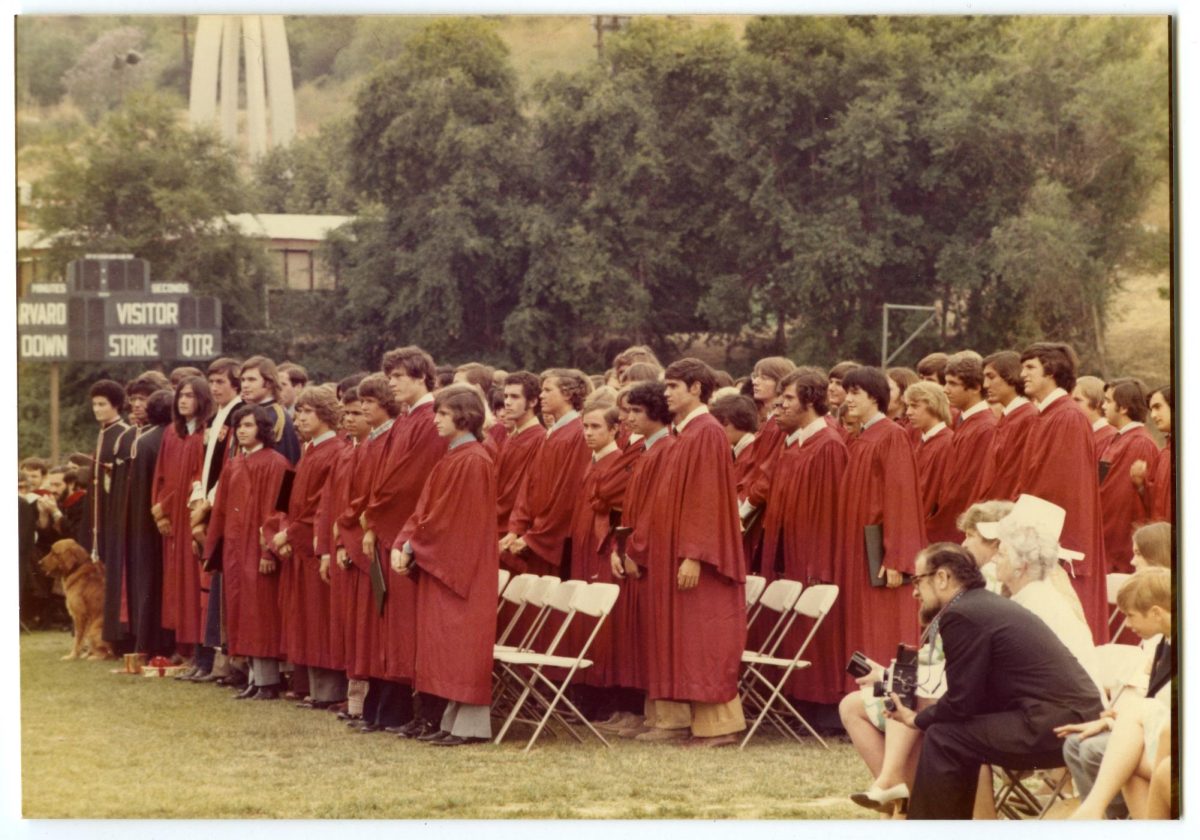

The school’s college admissions system is run from the room outside of Slattery’s office in Chalmers, where Dean Coordinators Camille da Santos and Lynn Miller collate and submit every student transcript and recommendation letter. Da Santos said a typical student submits around 10 to 15 applications. In 2021, for instance, the school’s 283 seniors submitted 2,810 applications to approximately 240 different colleges and universities, da Santos said.

“The crunch time in October and November is definitely one with no downtime,” Miller said in an email. “But we are used to it and enjoy the process. The time with our students is time that we love. It is also an incredibly gratifying process in which we are lucky enough to be able to participate.”

Recommendation writing follows a well-established schedule with only a few months of rest each year. Just when the college admissions process ends for seniors every spring, juniors begin asking for letters for fall applications.

Sawyer Strasberg ’22, who asked his English and Physics teachers to write his letters of recommendation, said he felt the process went smoothly.

“As soon as I started the conversation, they knew exactly what I was asking for because it was just that time of year,” Strasberg said. “So while it was a little nerve-wracking, once it was done, it was easy. I decided pretty early on that I wanted one STEM teacher and one humanities teacher. So once I had asked them, I almost felt like it was out of the way. Even though I sent them thank you notes, I never really had to think about it again.”

Medawar, who said she cannot recall ever saying no to a student, prepares for her letters long before she starts writing in the summer.

“When I know I am going to be writing recs over the course of the year, I will save things that students have written where I see that they revealed something really interesting about themselves,” Medawar said. “I will try to remember that or retain it or somehow put it somewhere so that I can do my best to bring the student to life on paper because my understanding is that colleges want to know how a student’s brain works. If I can just have a college admissions officer read my letter and say, ‘I have a good sense for how this kid’s mind works,’ then I have done my job.”

Teachers discuss the pressure they feel to produce high-quality letters

Upper School Teacher Craig * said in the past, he has written around 30 letters each year but felt the need to cut down in order to submit his best work.

“I think students have this general expectation that teachers have to say yes,” Craig said. “I do not think it’s a problem necessarily, but I just do not want to be misunderstood. The reason I am saying no is because I think the students can get a stronger letter elsewhere. That is ultimately what I and I think any other teacher would want the student to do.”

Craig said once he has said yes, he feels a responsibility to write compelling letters for his students.

“We are supposed to do this, and I think it is like any other expectation [for teachers], like grading,” Craig said. “So I just handle it, and I make sure that it gets done. If it does not get done, the kid does not get into college, and it is my fault. That is not something I could have on my conscience.”

Burton said while writing letters can be intense, especially in the fall, he still finds enjoyment in the experience.

“[Writing letters of recommendation] is extremely stressful,” Burton said. “I should personally start during the summer. Starting it during the fall makes the fall a very stressful experience. Still, I feel in that moment [when I am writing], what I am doing is not only kind of reflecting on that person’s growth, but also, hopefully, in some sense, rewarding them for all the time that they put in, the effort to go the extra mile, to work harder.”

While the teachers’ letters reflect a student’s experience in the classroom, the deans’ letters draw on a variety of sources, Cuseo said, including confidential teacher comments collected in a system called “Vannas,” named after former Director of College Counseling Vanna Cairns.

“The most effective route is one where there is a theme or a narrative,” Cuseo said. “We are not just going, ‘Here is the academic credits of the student, here is what they do extracurricularly, and we recommend them to you.’ It is kind of like writing an essay because you assert certain qualities, then look for evidence. For us, rather than literature or research, we get it from the teachers in the junior evaluations.”

Slattery said the deans strive to find qualities that make each student special.

“Maybe you have a kid who is extraordinarily kind and does tons of community service,” Slattery said. “You really want to lead with that narrative. Sometimes people worry, ‘Am I going to get a good letter?’ You’re always going to get a good letter, nobody is going to agree to write a letter if they cannot write a good letter. It is just that how they are structured is different, depending on the student and what they are good at.”

Once a student has asked for a letter in the spring, Medawar said, their interaction should not be over.

“If I have taken the time to do the work during my summer months, I think it is really important for students to keep in touch about their process,” Medawar said. “Sometimes, students do not do that. That does make teachers feel a little bit, it is a strong word, but ‘used’ when a student asks you in May for a recommendation, and they do not ever come up to you to say, ‘Thank you,’ and ‘This was my result,’ or ‘This is what happened for me.’”

Once teachers have finish their letters, they submit them digitally using Scoir, an online tool the school uses to organize and submit application materials.

Over the last five years, students have matriculated to 180 different institutions worldwide, according to the school’s website. Despite so much emphasis on college admissions, Slattery said she cares more about good fit than about prestige or selectivity.

“I do not actually care where all of you go to college,” Slattery said. “I am proud of you all. I want you guys to end up at places that feel like a good match, but the actual names of the schools or whatever does not matter to me. I am just as proud when somebody goes to a place that is not super selective, that was a good match for them, as I am of the kids who go to an Ivy League school.”

*Name has been changed