Grade A Friendship

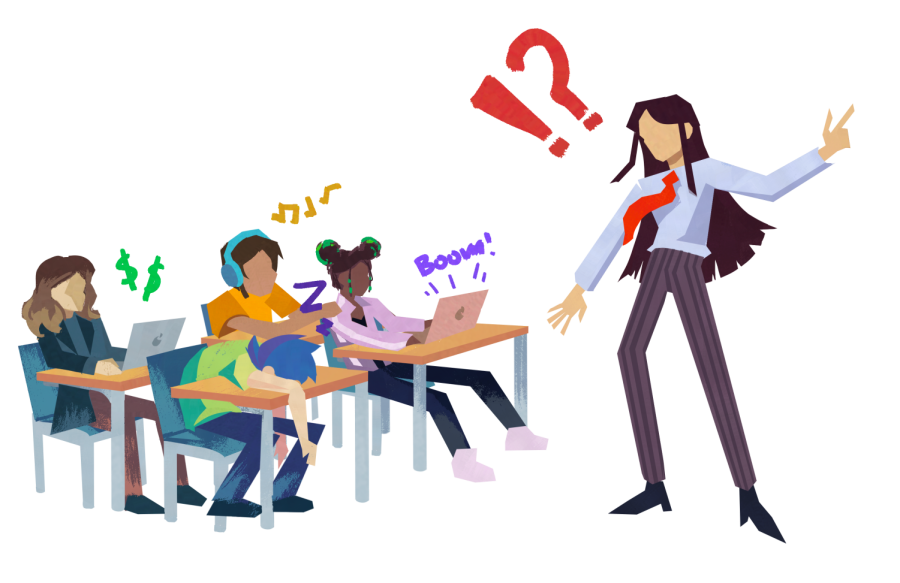

An illustration depicts an angry teacher lecturing inattentive students.

March 22, 2023

Garrett* sat in the back of his math class with his computer open. He watched as Guest6598344956 moved a knight and waited for his own turn in his chess game. Meanwhile, his math teacher lectured about polar coordinates in the background. Garrett, like many other students, said he frequently plays games in class.

“I only play games on my computer in classes that don’t really matter and are easy,” Garrett said. “Like in math, I don’t think it really affects [my grades] too much. Also, in Spanish, my teacher knows that I am playing chess, but she doesn’t care. I play [games] in classes where I don’t need their help and where I don’t really need to talk or interact with the teacher.”

Garrett’s constant laptop usage is a common experience for teachers. History Teacher Dror Yaron said he often notices students are distracted when they are on their computers.

“Rarely do I find a student solely engaged in note-taking without seeing their wandering finger,” Yaron said. “I immediately will call on them and say, ‘So what do you think?’ and they’ll jump. It’s like putting candy in front of a small child, like a lollipop, and saying that you can’t lick it, but you can play with it with your fingers. A big robust, juicy, sugar-filled, fructose lollipop. It’s very damaging.”

Yaron said students would be more engaged in class if there were stricter rules about devices in class.

“If the administration laid down the line and said, ‘No cell phones, and no computers,’ in the long term, it would be tremendously beneficial for everyone’s well-being, mental health and engagement with each other,” Yaron said. “[It would be] an active positive culture in the school, quite frankly.”

In addition to facing issues with technology, Yaron said few students seem devoted to learning without first worrying about their grades.

“Rare is a student that exclusively––and maybe this shouldn’t be the case––that really is focused, first and foremost, on inherent curiosity and investigation, and grades are secondary,” Yaron said. “I don’t blame the students, though. They’re part of a system that has generated an environment of competition.”

Yaron said he worries many students take grades as a representation of their worth.

“The grade that one earns is not a reflection of the person––it’s a reflection of the work that they undertake,” Yaron said. “It’s a reflection of the preparation, the choices, the priorities or just circumstances. I wish, in an ideal world, that grades were not as impactive, but we are made up of a community that’s very type-A personality, very hyper-competitive, very much oriented towards status, and status and in the sense of attaining the highest status of college ranking.”

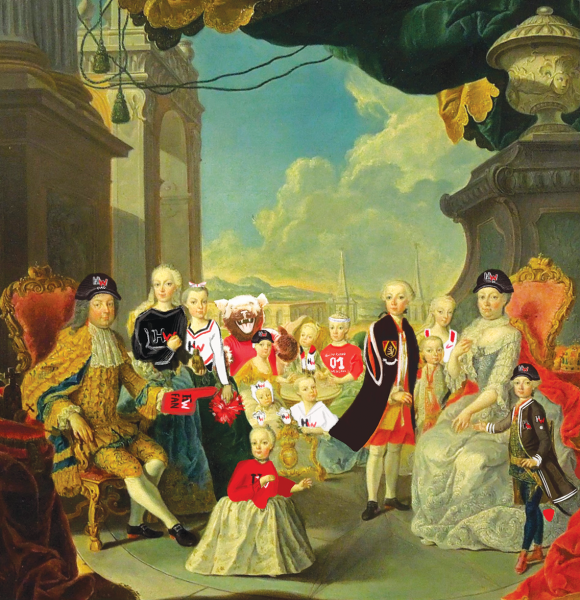

Yaron said he solely gives grades based on merit and not based on a student’s perceived effort.

“I love Harvard-Westlake, and I love the students, and I love engagement with them, and obviously at the immediate level, I want to appease and appeal to students where I can, but at the end of the day, I will never succumb to the idea that me giving high grades is some kind of unwritten agreement that [because] I really like you as a student and know you tried really hard, here’s 105%,” Yaron said. “I think you’re discrediting the student. You’re discarding their dignity as a human being.”

Like Yaron, Nuzzy Sykes ’24 said he appreciates his relationships with teachers, but they primarily depend on his interest in the subject.

“If I have an interest in what’s going on, I’m going to be able to interact and relate to the teacher a lot more through the topics that they’re teaching, than if I’m trying to make small talk with them,” Sykes said. “Some teachers will make jokes in class, and I like some teachers that naturally make their classes engaging and fun.”

Sykes said he feels connected to many of his teachers, even if their relationships with students are impersonal.

“I’ve definitely had my [situations]with the teachers [where] they just say ‘Get this work done, I’ll grade it and then I’ll see you at the next class,’” Sykes said. “Sooner or later, they’ll tell some story or interact in some new way that brings another depth to them. So, there are definitely some teachers that establish more of that personal connection than others, but in general, I feel like all teachers have some level of humanity to them.”

Cole Hall ’24 said he has forged close friendships with his teachers as a junior, especially because junior year can be difficult.

“This year, [teachers] are definitely way more friendly,” Hall said. “I’ve been told not to disclose which teacher I call by their first name because he doesn’t want to — he was like, ‘that’s like a terrible look, and you’re not actually allowed to do that’ — but I do call so many teachers by the first name, and most of them have nicknames at this point. I’ve grown a lot closer with a lot of them just because this is definitely a pressure-cooker year, and teachers kind of understand that. I feel like the teachers now, compared to all my prior years at Harvard-Westlake, are just trying to create even more of a connection with students.”

Hall said he feels disappointed in himself when he does poorly on an assignment but has learned to get back on track.

“With my relationship with my teachers, when I get a bad grade, I feel like I kind of let them down in some way, especially when I do spend some amount of extra time with them,” Hall said. “I personally have definitely had like, ‘teachers suck’ moments, but I don’t think that’s happened this year. More so [I’ve] been like, ‘Okay, how do I hop back on the horse?’ just because I’ve been able to build those relationships with my teachers.”

When students receive poor grades, Science Teacher Nancy Chen said she may not give grades based on student effort but feels proud when her students try to learn and succeed in her course.

“For the students who put in a lot of effort and show a lot of growth, I feel very proud of them, because I know how much work it takes to understand something that you don’t really understand,” Chen said. “So I have a different set of feelings for them because I acknowledge that they’re working hard and am proud of how far they have come.”

Chen said she does not judge students who do not put as much effort into her course as she realizes they have other commitments.

“For the students who do understand the topics and [put less effort into my class], I understand that they’re still putting time into [my class], but they are also putting time into other classes,” Chen said. “[That is] why I do go to athletic events, musicals, or plays and band, because that effort could be put somewhere else that becomes more of a priority for them. Also, other subjects could be harder than my subject. So, I have to recognize that if they’re putting less effort in, that doesn’t mean that they’re not putting effort into who they are and what they’re doing to grow as a person.”

Chen said her relationships with students are not dependent on grades but are based on how much she knows a student.

“I would say my relationships with students do differ, but their performance doesn’t matter,” Chen said. “I tend to find that if I have more individual meetings with students and have more time getting to know them, my relationship with them gets stronger than it would in a class setting. Since the schedule change, I’m meeting with my students less, and it has been harder to get to know my students on individual levels. Having individual meetings makes our relationship a little bit better because students get more comfortable in asking questions than trying to struggle through the problem on their own.”

Math Teacher Eli Lieberman said student relationships can be strained and become more distant because of a student’s performance.

“The reason for detachment could come from previous issues with math, especially at Harvard-Westlake,” Lieberman said. “Sometimes, there’s a difference where [a student] has a certain set of skills and is trying to reach an upper level. It just gets frustrating [for the student] because it’s not always easy to reach, and students often pull back and say, ‘If I can’t get it, then what’s the point of trying?’. When it’s that kind of dynamic, there’s often resentment on the part of the student. I have a hard time bridging that gap because I’m the face of the guy who is saying, ‘I expect you to do this, this, this and this,’ and students have a hard time reaching that. In that case, I think it’s harder to have a warm relationship.”

Lieberman said he has varying degrees of closeness in his student relationships but always sees possibilities for stronger friendships.

“There’s always gonna be some sort of relationship with the student, and some are warmer than others,” Lieberman said. “In determining a warm relationship, I think it just comes down to natural rapport, where there’s mutual understanding. Sometimes if there’s not that immediate connection, then a warmer relationship could just come from the fact that I see the students working, and they see me trying to understand them and just kind of building up a mutual trust.”

Despite this, Lieberman said he believes students with negative mindsets are more difficult to have close relationships with.

“I think there are students who come in with issues: they hate math, and they just don’t want to do anything,” Lieberman said. “They come the first day, and they say in their head, ‘You’re not going to teach me anything’, and they’re right. That doesn’t mean that they’re not a nice person and doesn’t mean they’re not going to connect on a different level.”

In many of her classes, Junior Prefect Isiuwa Odiase ’24 said she feels comfortable connecting with her teachers on an academic level.

“I feel like a lot of my relationship with teachers is kind of business casual, because I feel like I’m able to rely on them when it comes to school things,” Odiase said. “Honestly, I feel like there’s only a certain set of teachers that I can rely on in terms of personal things.”

Head of Upper School Beth Slattery said the difficulty of a class or a teacher does not determine a student’s relationship with that teacher.

“We have plenty of teachers who are hard, but kids feel incredibly supported by them, and sometimes that relationship develops, and it’s really tight-knit,” Slattery said. “In an ideal world, all of our teachers are conveying a sense of support and care for all of their students. Sometimes, just naturally they might gravitate towards a kid, which happened to me as a dean, where you had a lot in common, or the kid confided in you a lot.”

Slattery said students have misconceptions about a teacher’s opinion of them because of their grades.

“Kids often believe that their grade is a reflection of how a teacher feels about them, and teachers never think that is a reflection,” Slattery said. “You could have a favorite student that isn’t doing well in your class. It’s important to really divorce those two things.”

Slattery said grading is less biased than students believe.

“Our teachers are professionals, and they make sure they’re norming the way that they grade,” Slattery said. “They have rubrics, and it’s not like the sorting hat in ‘Harry Potter.’ They don’t just decide that somebody belongs in the A, B or C category. So, I get why kids think that, but most of the time, when they do round grades, it’s really [that the students] are kind of within the A- or A [borderline]. That is as equitable as it can be.”

Odiase said she occasionally feels a close and personal relationship with some of her teachers who are receptive to her concerns and mindset.

“I appreciate that there are some teachers I can rely on for personal affairs, like if I’m not in the mental mind space that I should be in to understand the lesson being taught, there are certain teachers that will give me that day and allow for an off day,” Odiase said. “With these teachers, it’s almost like having an aunt or uncle on campus. They lecture you and give you the information that you need to know, but, if you need them, they’ll be there for you and tell you what you need to do in a certain situation.”

*Name has been changed.