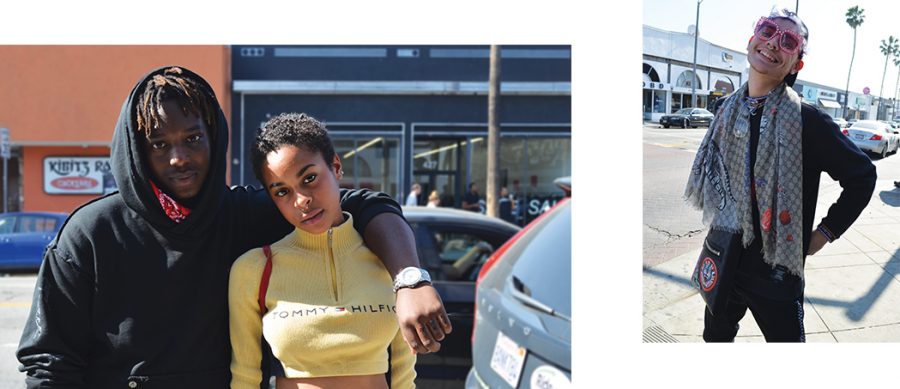

Máté Major ’18 likes routine. During the school week, he wakes up at 6 a.m., battles traffic on the 101 in his 2007 Honda (“the village donkey”), goes to his classes and goes home. He might go to a La Femme meeting during break and on Mondays, he goes to Peer Support. Recently, he’s been working on college applications, but if it were up to him, he would cook a meal or go on a hike with his family like he usually does when he isn’t overwhelmed with work. As a new junior last year, he found friends in the class of 2017, last year’s senior class. He tries to keep in touch with them, but it’s hard, him being in the middle of the college process and them being busy college freshmen.

He may seem like a typical teenager making his way through high school, but any day Máté could receive a notice in the mail that could take away this “normal” life. Máté immigrated to America from Hungary in 2014 after his father, an economics professor, was contracted to teach at the University of California, San Diego. He first came with a temporary, non-immigrant visa, but made the decision to stay and apply for a Green Card the same year. Now, over three years later, he’s still waiting for United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to accept or deny his Green Card application. When we asked him when he’ll receive the decision, he shrugged. It could be tomorrow or a decade from now, he said.

He’s adopted a “one step at a time approach” to life, learning not to plan too far in advance, knowing that his future is largely uncertain.

“I don’t know if you would ever find anyone saying that they just love waiting for a green card,” he says. “I would rather have a definitive answer and know what my next move is or has to be. Again, it’s just disempowerment. You’re suspended and you’re not going any which way.”

But Máté accepts the situation for what it is.

“It’s a gamble, I knew that coming in,” he said. “The fact that I am in this limbo, if you will, and have been is just part of the deal, more or less.”

This gamble was one that he himself decided to take. Since his father lives in San Diego, he lives in Los Angeles with his sister. He was given the option of returning to Hungary and living with family there, or staying in Los Angeles with his sister. He opted to stay. Although he still considers Hungary his homeland and his country, he recognized there were more opportunities for him in America.

“I looked at what would’ve waited for me back in Hungary,” he said. “Hungary is still a European country, and we are by no means a developing nation, but it is a post-socialist country with a lot of corruption. [There are] not too many opportunities for young people for quality higher education. The government has centralized all power and is basically censoring education. You cannot leave the country for ten years if you decide to get a degree at a Hungarian university. It is a very restrictive and somewhat oppressive country, and that did not quite sit with me knowing that I had the option to move to America, because who wouldn’t want to do that?”

Similar to Máté, Hunter* emigrated to the United States from a European country on a temporary visa. He asked that his name and the country he emigrated from not be printed to protect his privacy. However, he had one reason for staying and applying for a green card: attending Harvard-Westlake.

Unlike Máté, Hunter’s decision to stay was made largely for him by his parents.

“It wasn’t an easy decision for me,” Hunter said. “I didn’t make the decision. It was an easy decision for my parents. I mean, granted I’m on financial aid, so I’m not paying all of the tuition. All the money my family ever owned would probably [not] be enough to live in America and go to this school, just based on [my family’s] employment. The fact that we got financial aid meant that it would be a sustainable thing to do, but also it’s a really good school, right? And it is in America. So for them the decision was very easy.”

Despite how easy the decision to emigrate was for his parents, Hunter struggled with the prospect of uprooting his life. He said leaving Europe meant leaving his entire family and moving to a country where he did not know anyone his own age.

“Obviously I couldn’t have carried every single one of my friends with me or taken them to America, so it’s a difficult thing, and probably what makes it most difficult is the feeling of familiarity and similarity that you have in a community that you grew up in,” he said. “You go, ‘Ok, I guess I just won’t have that for a while.’ Anything you can think of—teachers that I liked, friends that I had, family relations, just habits, like every Tuesday I took violin lessons and I took that bus and I would ride from here to there, and I would get off at that stop. It all had a feel to it. And that sort of thing is completely gone.”

Máté also left behind much of his family when he moved to America. Although he tries to stay in contact with them, he said they often don’t have access to internet, which makes communication valuable but also infrequent.

“My great grandmother passed away a while back,” he said. “She was very old, I think she was 95 or 96, but learning about her death through an email, it really drove home the fact that I’m as far away as can be.”

Despite the difficulties of moving to Los Angeles, “it is what it is,” Máté said. What makes it worth it to both Máté and Hunter is the greater educational opportunity in America.

“If I went to the best school in my country, I may have tried for an application into Britain. I would not have even dreamed of sending an application to, like, ‘insert name of great college here,’” Hunter said. “The fact that I have this opportunity here now is basically what the main reason of moving out was.”

Máté said the benefits of receiving an American education extend beyond attending a prestigious college. Since moving to America, he has had a more enriching high school experience, he said.

“I really enjoy studying, which might be shunned by some, but this school has facilities that go beyond measures [compared] to all of the other schools I’ve attended,” Máté said. “That doesn’t get lost on me and I want to use that to the utmost extent. Whenever I feel mopey about the homework I have, I remind myself that is why I’m here. To get the most, and to me that’s learning as much as I can.”

Although they have both made sacrifices for their education, there are still additional hoops that they must jump through in the college process that come with not being an American citizen. This includes the lower probability of receiving financial aid for college tuition compared to students who are citizens.

“Most colleges aren’t nearly as generous as Harvard-Westlake is,” Hunter said. “Where I go from here is who gives me the most money.”

Hunter, however, doesn’t want us to feel bad for him. His outlook on life is still one of gratitude.

“I realize that I don’t have all the money in the world, and I’m not sure what I’m supposed to say,” he said. “I don’t think it’s unfair and I’m not saddened by this fact. I realize that even if I have to restrict my options to whichever college gives me the most money, that’s still a whole slew of universities I never would have thought of had I stayed [in Europe].”

Besides the obstacle that financial aid presents, Hunter recognizes that he is also disadvantaged in starting the college process later than other students.

“This train, this ‘getting to college rat race’ that you guys are in, starts very early,” Hunter said. “I started late. So, in hindsight, I get a late start on the whole college thing, and by that I mean basically everything—the amount of APs that you can take, whether you think you should be taking [them] or want to take [them] . I didn’t even know what an AP class really was, so I said ‘Ok, I guess I’ll take two, that’s fine,’ whereas most people took more than two.”

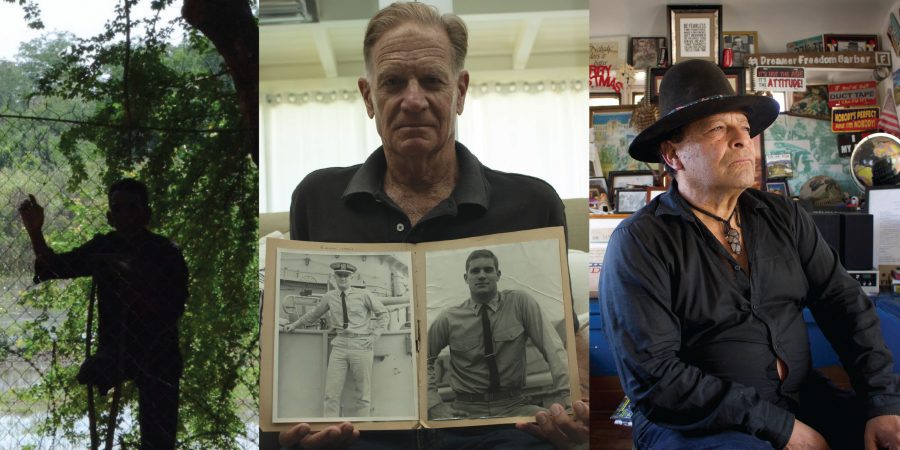

Although neither Hunter nor Máté consider themselves to have the extenuating circumstances that they believe many students in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program have, both agreed that there are some similarities with their current status. Máté has been waiting for his Green Card for over 3 years. Hunter declined to state how long exactly he has been waiting for his Green Card, but it has been over a year.

DACA recipients are unsure of the future of the policy that allows them to legally stay in America following President Donald Trump’s announcement Sept. 5 that his administration intends to end DACA if Congress does not reach a deal to extend the program by March 5. After that date, DACA recipients could face deportation.

Jens Hainmueller, a professor of political science and a head of the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford University, helped lead a study that found that DACA protections significantly improve the health conditions of people enrolled in the program, according to news.stanford.edu.

“Childhood mental health problems are associated with serious challenges later in life,” Hainmueller said. “Struggles in school can lead to limited job prospects and long-term reliance on welfare, and adults who experienced trauma during these formative years have higher rates of substance abuse and chronic health problems.”

Hainmueller said that these health problems during adolescence can have long-term negative effects during adulthood.

“By curbing acute anxiety in young children, programs like DACA could have cascade effects in improving health and other outcomes across the lifespan,” he said. “In addition, there are significant implications for costs given that childhood mental health disorders account for the lion’s share of pediatric health care spending in the U.S.”

Máté said that the biggest frustration that comes with being in the waiting phase of finding out whether or not he can continue living in America is his sense of helplessness in deciding his own fate.

“It’s always present,” Máté said. “I’m constantly in this situation, but I also cannot change it. There are very clear limitations to what I can do to affect the situation that I’m in.”

He treats the obstacles he’s faced in applying for citizenship as learning experiences and remembers to keep things in perspective.

“I gained perspective from this,” he said. “I know that I’ve been saying this a lot, but it is one of my favorite words. Putting everything in perspective can help with a lot of predicaments we face in the first world. We often get sidetracked and terribly consumed by things that might not matter all that much.”

Until he hears back from the USCIS, he waits. He still loves living in the city. He does it every day, but driving down streets lined with palm trees, rarities in Hungary, never ceases to blow his mind.

*Names have been changed.