Good for a Girl

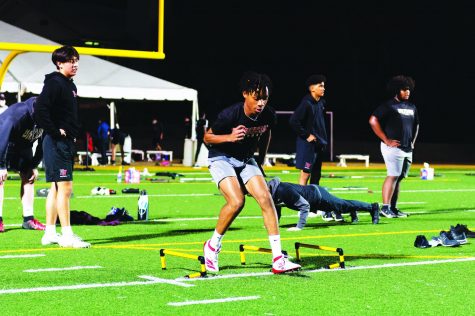

Kiki Iriafen ’21 looks to shoot the ball in the CIF-SS Division I Championship in 2020.

June 1, 2021

At the height of the 2021 NCAA Division I Women’s Basketball Tournament, girls basketball player Kiki Iriafen ’21 scoffed at the sight of the pictures of the women’s undersupplied weight room posted on Instagram. Looking at the lavish training facilities the men’s teams received at the NCAA March Madness Tournament, Iriafen said she felt defeated. Even for Iriafen, a five-star Stanford University commit currently ranked No. 19 by ESPN for women’s basketball, gender inequality and sexism in athletics is old news.

“I wasn’t surprised, honestly,” Iriafen said. “It’s disappointing, and it’s awful, but it wasn’t surprising at all, especially in that big of a stage. When I saw the picture, I was just so sad.”

The treatment of women’s basketball players at March Madness sparked controversy and public outrage, as it reflected the value society places on women’s athletics, both at the professional and high school levels.

According to an analysis done by the National Women’s Law Center of 2011-12 Department of Education, there are nearly 4,500 public schools in the U.S that could be in violation of Title IX, which requires all federally funded educational institutions to provide equal access and funding to all athletes, regardless of sex or gender.

Although the school is a private, non-profit institution, former varsity field hockey team captain Astor Wu ’20 said she feels the school is complicit in perpetuating the stereotype that women’s sports are unimportant. Despite her squad going undefeated for three consecutive seasons during Wu’s tenure, she said the allocation of field space relative to boys sports was unequal and that this same implicit “less than” message meant that community support and attendance at field hockey events was consistently lower than it was for boys sports.

“I never was on the team at a period where we were respected in the same way as a male counterpart sport,” Wu said. “It was definitely frustrating at times to see how much attention football received, or maybe baseball or boys water polo. I believed that me and my teammates were working equally as hard on the field and even winning and so that was definitely frustrating.”

Despite Wu’s frequent disappointment with the lack of attention and respect the field hockey team got from both the student body and the school, she said she felt powerless to fix the situation.

“If we were standing on the sideline, waiting for football to get off and for us to start our practice as a varsity winning team, that’s a little bit demoralizing,” Wu said. “Especially as the captain of the team my senior year, I really felt like I couldn’t do anything about it. Because I had seen the captains before me try, and nothing happened. We were just constantly shut down. I feel like I was told that we were overreacting or that it just wasn’t a big enough deal to fix. We were treated [as] relatively disposable at times, and I just feel like we were really underappreciated.”

Although field hockey player Sarah Rivera ’21 said she is satisfied with the number of fans and classmates that come to watch her squad’s games, she thinks most of the inequality stems directly from the school’s lack of respect for the sport.

“It gives a feeling as though the field hockey team is something the school can find pride in until it comes to asking for something more than a school bus to ride to away games, or even better, sticks and more balls for those who are just starting out for the first time,” Rivera said. “Although we have respect locally from students, parents and teachers alike, a lack of funding conveys the message that no matter how well we do or how hard we fight, our extremely skilled program will always struggle with finding respect from the school itself.”

Football player Sonny Heyes ’22 said he agrees with this sentiment, as he said he notices that the football team enjoys more fans and special treatment from the school, such as getting better field times and more publicity.

“I think the football team enjoys a lot of privileges, like convenient field time, complete access to the weight room and televised games,” Hayes said. “I don’t think that the field hockey team enjoys those privileges to the full extent that we do.”

Head of Athletics Terrence Barnum responded to claims of gender inequality by stating that all sports, regardless of gender, receive equal treatment.

“We are extremely proud of our girls athletic teams,” Barnum said. “Girls sports have enjoyed great success at our school, regularly winning league and CIF championships. We are committed to supporting and promoting our girls teams as much as we do our boys teams. Girls games are featured on HWTV and highlighted via our various social media platforms. We want all athletes to feel an equal sense of belonging.”

Iriafen said she felt that the school treated the girls and boys basketball programs equally, yet she said that her peers frequently diminish her success in the sport because of her gender.

“The one thing I get the most is guys saying, ‘you’re pretty good for a girl,’” Iriafen said. “It’s never, ‘you’re a good basketball player.’ It’s always, ‘you’re a good girl basketball player.’ It always has to be a gender thing. Guys not really seeing me as a basketball player, but forcing me to be a female basketball player and not giving me the same respect that they would another male basketball player.”

Although Wu and Iriafen agreed they want more fans at their matches, starting varsity outside hitter and Villanova University women’s volleyball commit Skylar Gerhardt ’22 said students didn’t come to her games to cheer for the team; instead, she said they came to watch the girls in their uniforms.

“The guys made [me] feel kind of uncomfortable,” Gerhardt said. “If they’re just looking at [my] butt the whole game, and I think most girls kind of feel that way on volleyball. As a girl, that’s always in the back of my head. I’m always adjusting because I don’t want my shorts to ride up too much, and I always pull them down because I don’t want to be sexualized in the stands or be embarrassed when coaches and parents tell me my shorts are too short.”

Gerhardt said the sexualization doesn’t stop on the court. Oftentimes, she said her peers send her posts on social media degrading women’s volleyball or women’s sports in general, which discourages her as an athlete.

“When I see posts like that it makes me feel frustrated and sad,” Gerhardt said. “I feel women already get less respect than boys and men’s sports so it is upsetting. I wish things were different in that people stop feeding into posts that degrade women and women in sports. It is already hard enough always feeling compared to and getting less than men in sports, so comments and posts sexualizing young women is very annoying.”

Whether women’s athletics is sexualized, ignored or disrespected by peers or institutions, Iriafen said the consistent help and encouragement of professional male athletes and her male classmates is vital to ameliorate gender inequality and sexism in athletics. This, she said, will allow female athletes to receive proper recognition and resources at both the high school and professional levels.

“I will say that the NBA players have a lot of influence, especially with their fans and everything,” Iriafen said. “If men support women’s basketball, I think that helps a lot. Because those same people [who] are making comments about women’s basketball and diminishing it, they can see the people that they look up to supporting women’s sports. So I think that’s really positive, and that’s a step in the right direction.”