Expanding Financial Aid

June 6, 2021

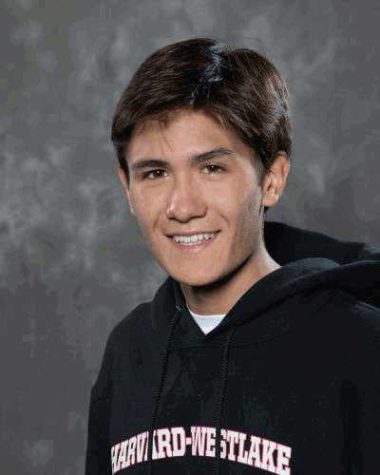

While other athletes on the boys golf team purchased new equipment before the season, Ford McDill ’21 browsed the thrift store for golf clubs. Later, at practices and competitions, he noticed the differences between his pre-owned gear and his teammates’ new equipment. McDill recalled his experience on the school’s golf team, which left him feeling slightly estranged from his teammates at times.

“[While I was on the golf team,] people didn’t make fun of me, but I just felt a little out of place when people had the newest expensive [clubs], and I was kind of stuck with these secondhand things,” McDill said. “I think there’s a little bit of a stigma towards people on financial aid, but nothing major or too serious.”

McDill announced the creation of the Financial Diversity Group, an affinity group for students receiving financial assistance from the school, in an upper school assembly last year.

“I said, ‘I’m on financial aid, and it’s great,’ and then everybody laughed,” McDill said. “I like to think it was a joke, but it was a little bit, I think, because I was on financial aid. I feel like [the assembly] changed how some people viewed me, even though it was just a little thing.”

Director of Financial Aid and Upper School History Teacher Greg Gonzalez said that one of his goals is to erase any stigma associated with receiving financial aid.

“We’re trying to normalize it,” Gonzalez said. “We’re trying to make it so it shouldn’t be unusual to be on aid. It should be normal, and it should be something we celebrate more.”

According to the school’s website, 315 students, about 20% of the student body, receive an average grant of $31,000, which is about 75% of the school’s tuition. Financial aid at the school is need-based, rather than merit-based, and the school provides 100% of its students’ needs. Need is determined by a family’s assets and income relative to tuition. Students receiving aid also benefit from an account for the school bookstore and cafeteria, as well as help purchasing books, course-related materials, athletic team-required clothing and equipment and school-related trips.

“Our philosophy is that all our students have merit, so the best way to determine financial aid grants is through need,” Gonzalez said.

McDill said that such efforts demonstrate the school’s continued support of students receiving financial aid.

“When quarantine started, [the school] sent out an email and asked if you need headphones or [supplies] for back to school,” McDill said. “It did seem like we were important.”

The school allocated $13.7 million to financial aid this year, significantly more than nearby independent schools such as Brentwood School ($7 million), Polytechnic ($5.2 million) and Windward School ($2.3 million), according to each school’s website, and at higher or comparable rates of each institution’s student body.

Despite the school’s comparably large financial aid program, most students continue to come from families of great affluence. Ethan Rose ’22, who is not on financial aid, said he can see how this might impact the social experience of students from less wealthy families.

“I’ve never witnessed anyone be bullied for their financial background, but you definitely see people flaunting their wealth, so I definitely understand why someone who does not come from a wealthy background might feel uncomfortable at times,” Rose said.

Alumnus Axel Rivera-de Leon ’18, who was also a financial aid recipient, characterized his early experiences at the school as difficult. He now attends Stanford University and works as a research assistant at Stanford Medicine Brain Stimulation Lab.

“Entering a space like Harvard-Westlake as a queer Latino seventh grader from a low-income family was alienating and demanding,” Rivera-de Leon said. “Harvard-Westlake as an institution was intimidating and unwelcoming for a young queer kid. Support was there if you sought it out, which I eventually learned to do.”

Rivera-de Leon also said there were fundamental differences between students of varying financial backgrounds.

“There was a tangible difference between students on financial aid versus students not receiving aid,” Rivera-de Leon said. “I feel that Harvard-Westlake tried to minimize the difference in experience between these two groups and provide an equitable experience as an institution; however, the cultural and social differences based on socioeconomic status among the students are certainly still there. It’s deeper than whether you wear designer clothes to school, if you can afford to go off campus for lunch every day, or what car you drive—if you even have a car. As a low-income student, I see myself, treat others and navigate society differently than the people at Harvard-Westlake with massive amounts of wealth. We were simply shaped by different backgrounds.”

Gonzalez said he helped create the Financial Diversity Group in part to address the social inequities that can come with receiving financial aid.

“If we are encouraging students to welcome each other, their financial backgrounds shouldn’t matter to people either,” Gonzalez said. “That’s something we’ve been working on. Last year, we began the student Financial Diversity Group, and that’s one of the things we began discussing, and I think the students who went to the group found that there was no single type of student, they were surprised to see each other and they were grateful to find out [they’re] not alone.”

Since 2012, the financial aid budget has grown from $7.6 million to this year’s $13.7 million––the number two line item in the school budget behind faculty salaries. The financial aid program draws from the school endowment, donations and fundraisers, including the annual Spotlight Dinner, which honors students and alumni who benefit or benefited from financial aid. This year’s honorees are being recognized in pamphlet form.

Gonzalez said he is still looking to expand the school’s financial aid initiative.

“We’d like to grow the program [to cover] closer to 25% [of students],” Gonzalez said. “And then at some point, we’d like financial aid not to be a factor in admission and be need-blind.”

He cited the demographics of Los Angeles as one reason to continue to expand the school’s financial aid program.

“If you look at the entire population in Los Angeles, [based on] income and number of children, something like 85% to 90% of all students would qualify for financial aid, so that means we’re not drawing from the entire city,” Gonzalez said. “If we are able to tap into those students who qualify for aid, then one metaphor you can think about is [it’s] like we’re picking an all-star team from a giant pool, and the quality of the school would rise.”

Rivera-de Leon credits the assistance he received from the financial aid program as a contributing factor to his ability to pursue higher education.

“Ultimately, financial aid allowed me to reach my full potential by preventing money from being a barrier to success,” Rivera-de Leon said. “Financial aid removed financial barriers throughout the college process and allowed me to be as competitive as my peers. It provided me with school supplies and a laptop, participation in sports and extracurriculars and access to school trips and events. Access to all these resources helped boost me to attend Stanford, and I am still grateful for the support of financial aid today.”