January 6: One Year Later

January 19, 2022

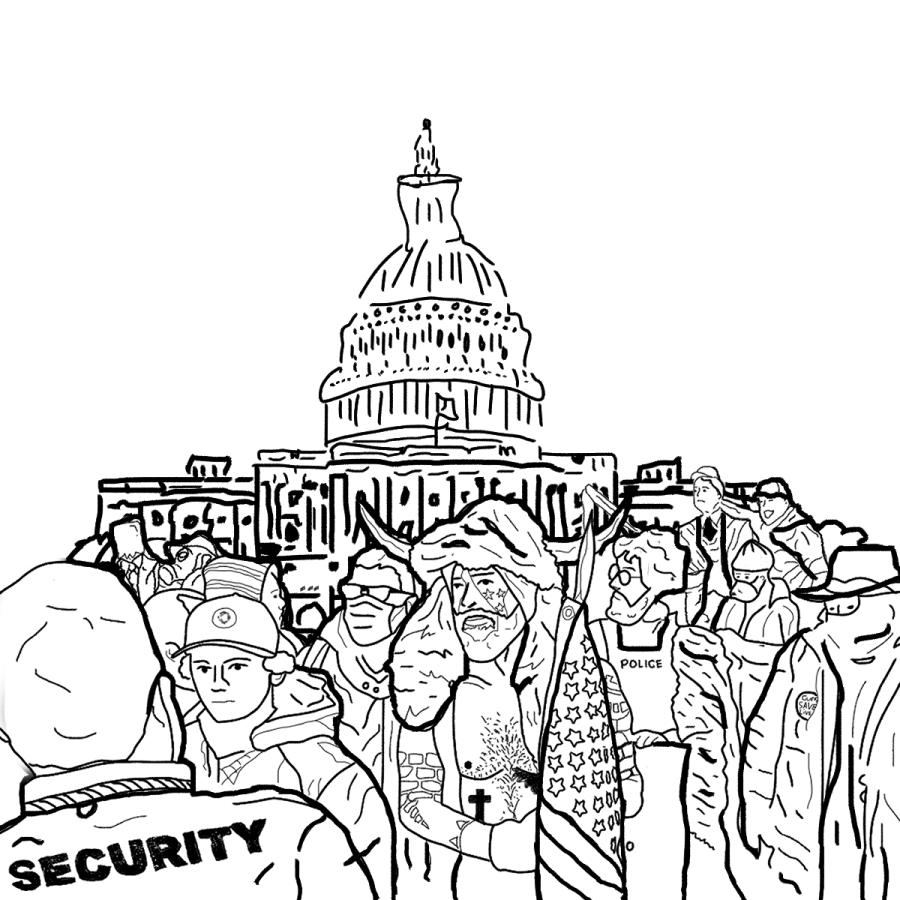

Struggling to pay attention in her physics class on Zoom on Jan. 6, 2021, Olivia Feldman ’22 had been zoning out before her phone began to buzz repeatedly. Overwhelmed by a creeping sense of anxiety and growing curiosity, Feldman flipped her phone over, watching as Twitter notifications about a riot at the U.S. Capitol flooded her screen. After her teacher assigned Feldman and the rest of the class to breakout rooms, Feldman began speaking to her classmates, disputing how many people were involved with the riot and whether it was a coordinated attack.

As the assault on the Capitol continued, Feldman said she was confused, scared and uncertain about what was unfolding.

“At first, I wasn’t really sure at all what was going on, and I was shocked that something of that caliber could happen in our lives in America,” Feldman said. “As the day went on and I saw more of the footage from the Capitol, it got more and more insane. The scale of it, and also the lack of protection of Congress and the election that was being certified. Even then, I don’t think I had any idea what the implications or the scale of this were.”

Feldman said the Jan. 6 attack was representative of how politically polarized the U.S. population has become. Feldman also said misinformation and social media algorithms’ tendency to feature extremist content were two additional factors in the riots.

The Capitol riots’ impact was felt by students and faculty alike.

“[The Capitol riots resulted from] massive polarization in America that affects all of us,” Feldman said. “Politicians have resorted to farming outrage and creating anger and hatred towards the other party to get votes and support for their legislation. That’s made it impossible to do anything via compromise or collaboration. It’s made everything very adversarial, and that has made people drift even further away from each other and towards extremes. Also, once a social media platform catches on to your political views, it just shows you more of that view and more extreme versions of it. You get streamlined into conspiracy theories and extremist views that can lead people to violence.”

Feldman said the Capitol riots will be remembered as an example of how fragile America’s democracy and destructive political polarization are.

“The legacy of Jan. 6 will be a concrete example of the effects of polarization and populism in America and the ways that those [value systems] can turn into violence and an uprising against our political institutions and the dangers of rhetoric and systems that turn people against each other to the point where they resort to storming the Capitol,” Feldman said.

Alumnus reflects on the political climate that sparked the Capitol Riots.

Alumnus Liam Sullivan ’21 said former President Donald Trump’s false claims of election fraud were the main reason for the attack on the Capitol, in addition to wealth inequality and government distrust. Regarding the impact of the attack, Sullivan said the Capitol riot furthered political divisions in the U.S., and the event is currently being exploited by the government as an excuse to restrict civil liberties.

“It’s definitely continuing to exacerbate political polarization,” Sullivan said. “The implications can only be bad, at least for American political discourse considering that the government is using it as justification to crack down further on civil liberties, just like how [9/11] was used as a pretext to crack down on more civil liberties.”

Sullivan said although the government’s response to the invasion of the Capitol is reminiscent of government restrictions such as the Patriot Act, he finds comparisons of Jan. 6 to Sept. 11 or Pearl Harbor as disrespectful to those impacted by the Pearl Harbor and Sept. 11 attacks. Harrison Altschul ’22 also said the Capitol riots on Jan. 6 are not comparable to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, citing the events’ difference in death counts and where the threat originated from.

“A lot of people think it’s similar to [Sept. 11] and in some cases, worse, to which I’ve personally disagreed with that,” Altschul said. “The events are different for a variety of reasons other than just the [casualties], with thousands [of deaths] on [Sept. 11] and just five [deaths] on Jan. 6. Obviously, this was a domestic threat on Jan. 6 from a specific group of Trump supporters, and [Sept. 11] was [carried out by] Al-Qaeda, a terrorist attack from a foreign threat.”

Altschul takes Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. Government and Politics, a course that covers modern political issues and the operation of the American government. Altschul said this discussion-based course provides an environment for students to learn and talk about current events such as Jan. 6.

“I’m quite happy with the way it’s been covered,” Altschul said. “I think that we’ve gotten to observe viewpoints from all sorts of parts of the political spectrum.”

Altschul’s AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher, History Teacher Peter Sheehy, said the Jan. 6 insurrection has already been and will continue to be implemented into the school’s AP history classes’ curricula, especially because he said the event encapsulates many current political issues such as political polarization.

“It certainly will remain an important part of the curriculum in [AP U.S. Government and Politics] and it will be discussed in AP [U.S.] History,” Sheehy wrote in an email. “It’s too soon to fully grasp the significance of the insurrection–we are still learning more about it every day–but it’s clear that it is an event of major significance. We can also study and learn from the present debates over what [Jan. 6] represents. The resistance to recognizing it as a serious assault on democracy provides important lessons about American exceptionalism, extreme partisanship and the impact of social media echo chambers.”

Community discusses what role politics should play in classroom settings.

Margaret Piatos ’23 said the insurrection was covered in her AP U.S. History class and should probably be added to future editions of history textbooks due to its significance and lasting impacts.

“We talked about how Jan. 6 could possibly be the end of the ‘[Sept. 11] era,’” Piatos said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if this was written into the next generation of textbooks and boo, if it hasn’t been already. I feel like this has been a key event in modern history and definitely would need to be included.”

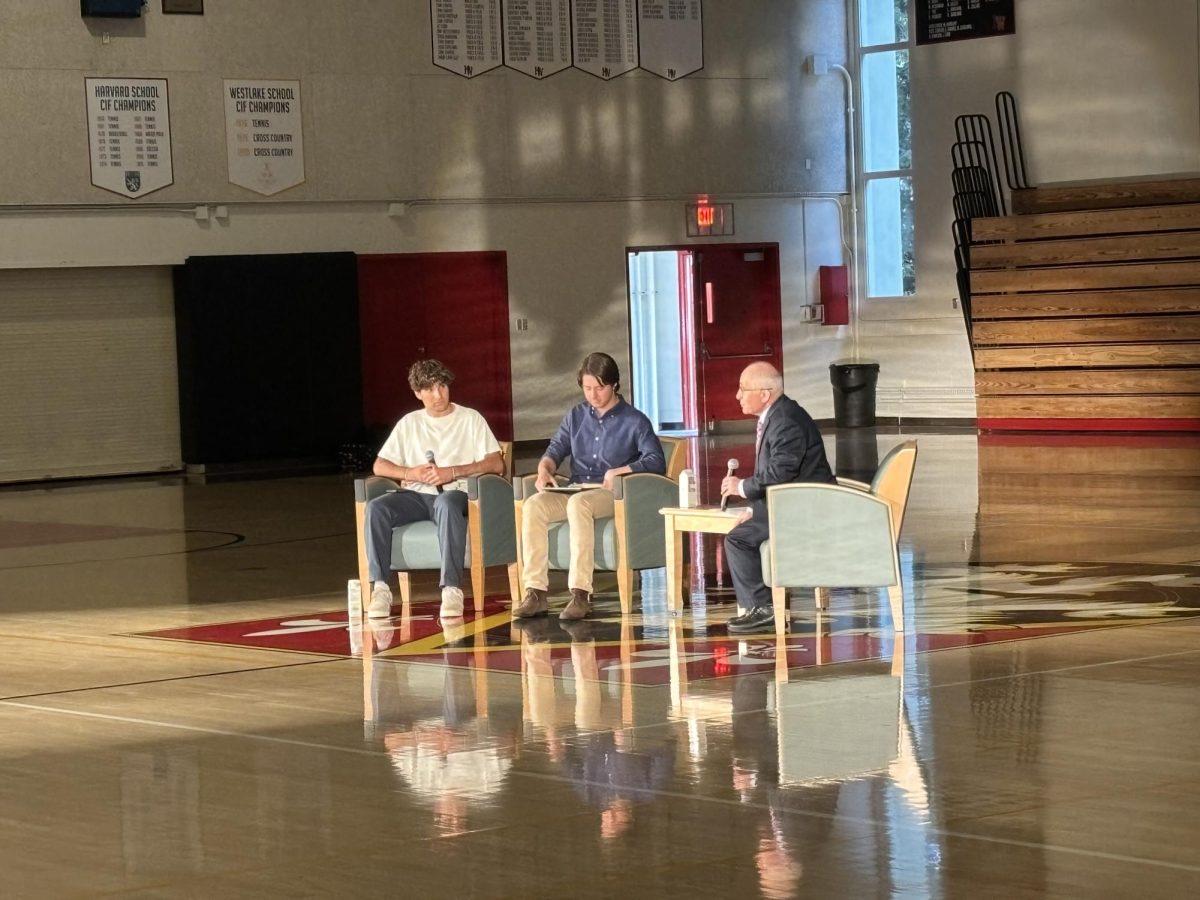

According to a Chronicle poll of 259 students, about 77% of respondents believe that political discussions in the classroom are appropriate whenever they are relevant to the course. Regarding the school’s history curriculum, Head of School Rick Commons said American history cannot be taught without discussing politics and said the Jan. 6 insurrection is an important part of U.S. history that must be studied in a classroom setting.

“It represents a moment in our country’s political history when many things that our country has stood for and has believed in were fundamentally threatened,” Commons said. “Classes, especially history classes, should take on the questions of why [American values] were threatened, how they were threatened, whether they should have been threatened or whether they should be preserved at all costs. I think those are really important questions to be raised and conversations to be had in the right moment in the right class led carefully by a thoughtful teacher.”

When recalling the insurrection, Judah Marley ’23 said she felt repulsed by images of Confederate flags and racist propaganda. Marley said she wishes for the Jan. 6 insurrection to be remembered as a warning to future generations of America.

“I truly hope that the only thing people, especially those of younger generations, learn from this horrific event is that something of this sort should never happen again, and we should be doing everything in our power to prevent something of this sort from occurring in the future,” Marley said.