The Name Game

Students of color reflect on how they have assimilated into American culture by changing their given names to more traditionally Western names.

March 29, 2021

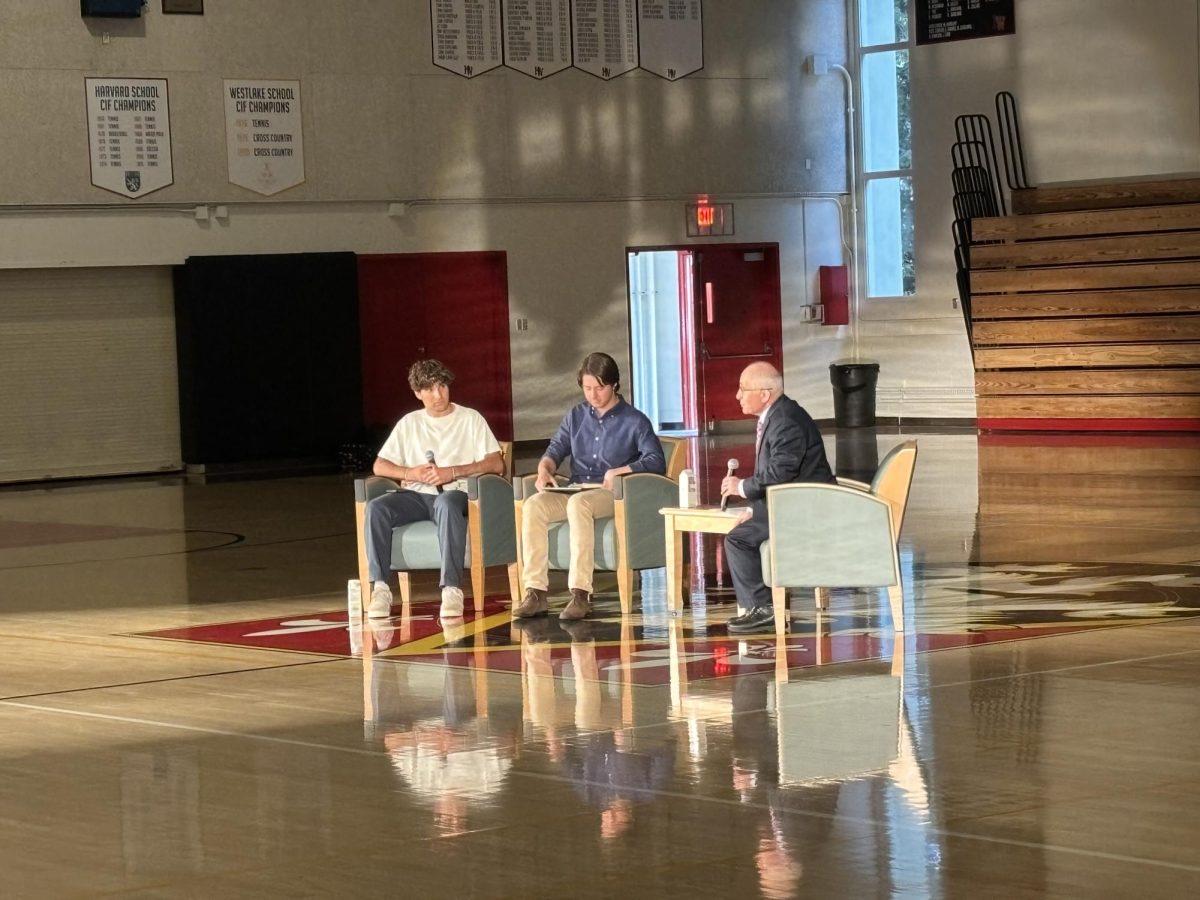

Late in her junior year, Kimberly Wang ’21 arrived at the Upper School to take her SAT Subject Test. She felt extremely nervous, but her stress for the exam was outweighed by an awkward situation. Instead of calling Wang by her given name, Xiaoyang, her proctor addressed her as “Mr. Wang.” For Wang, who identifies as a woman, the proctor’s ignorance was not something new, as she has struggled with others mispronouncing her name for her entire life.

“There have been countless incidents for as long as I can remember with pronunciation, which I completely understand because it is a hard word for [English] speakers to say,” Wang wrote in an email. “I choose to go by my English name because I have gone by Kim or Kimberly ever since I could speak English. Also, overall it is easier for people around me to pronounce, which means [correcting others less often]. ”

For students with names originating from different countries, having their names mispronounced is a common occurrence. In a 2020 study from the University of Alberta, 75% of the surveyed students with ‘ethnic’ last names said their names have been mispronounced.

Many students with these names have chosen to adopt new, easier-to-pronounce names in order to assimilate into American norms. A 2018 study conducted by the University of Toronto explored the prevalence of international students adopting “Anglo names.” From the surveyed group of Chinese international students, more than half took on “American-sounding” names. Cultural assimilation is the practice of minority groups changing one’s presentation and behavior to better integrate with the societal majority.

Canadian etymologist Mike Campbell traced the origins of English and American names to the 13th century when the Catholic Church encouraged people to name their children after saints and other religious figures. The United States Social Security Administration documented 100 of the most common names from 1920 to 2019, in which six out of the 10 most common male names and five out of the 10 most common female names had roots within Abrahamic religions.

While Wang said she has grown accustomed to people calling her Kimberly, she still feels a strong connection to both of her names.

“I was not born in America but still in an English-speaking environment—I think [my parents] wanted me to have a name that would be easier for me and those around me,” Wang said. “I go by my given name whenever I am speaking Chinese, [and] all my family and friends who speak Chinese refer to me by my given name.”

Similar to Wang, when Eghosasere Asemota ’22 immigrated to the United States from Nigeria, he said he started going by his middle name, Michael, so other people could address him more easily. After reflecting on his identity, however, he began using his given name in the classroom, a move that has since prompted varied reactions, he said.

“Most people were okay with [Eghosasere],” Asemota said. “I’ve had times where people try to say ‘Oh, can I just call you this nickname?’ Or like, ‘Can I shorten it?’ I’ve just said ‘no’ because I am not trying to change myself for anybody else this year.”

Asemota said this decision was part of an internal battle about becoming more comfortable with his name and taking pride in his African heritage.

“Why have I always tried to make other people feel more comfortable with what they call me rather than [being] comfortable myself?” Asemota said. “I’ve noticed that I have such discomfort with my own first name that I shouldn’t have. I shouldn’t be uncomfortable when I hear people say Eghosasere instead of Michael. I need to change that. I shouldn’t be allowing how others see my name [to change] my perception of my own name.”

Although Asemota said he would like to embrace his given name, he acknowledges the privileges that come with using an American name, especially with racial bias.

“When people see my [American] name, they don’t automatically assume that I’m Black,” Asemota said. “[I’ve had a] conversation with my parents about being in a professional setting [and how an American name] would help. A lot of the time people make assumptions based off of our names and how we look, so having a different name does get you through the door a lot of times.”

Aiden Cho ’22, who has used an American name since he arrived to the United States from South Korea, said he had a similarly uncomfortable experience when using his given name at school.

“The main reason why I didn’t like using my Korean name is that my name has a different pronunciation in Korean than in English,” Cho said. “It’s supposed to be pronounced YOON-JAE, but the English spelling is Y-U-N. So then people wouldn’t take it as seriously as I would’ve liked. They would be like ‘Yunjae, Yunjae’ whenever teachers called my name for attendance. It made me uncomfortable in that way, when kids are laughing. And it wasn’t the students purposely making [fun of my name], it was just natural, but it made me feel uncomfortable at school.”

Cho said his parents asked him to start using Aiden as his name because his Korean name would not be American enough.

“It would be hard for people to take me seriously as an American, and it would be hard to become accustomed to American culture,” Cho said. “So, even then, I knew there was always something about using a foreign name on American soil—it’s hard for you to become American.”

While Cho said he will continue using his American name in the United States, he uses his Korean name with his family, almost all of whom live in Korea. There, Cho said he feels most comfortable going by both names because many Korean people speak English as well.

In contrast, Colin Yuan ’22, who is Chinese American, said he identifies more with his American name because he has used it regularly since emigrating from China at a young age.

“I kind of have to assimilate, [and not] in a bad way,” Yuan said. “It’s not inherently uncomfortable for me. I don’t really feel forced to. Or I don’t feel bad about [using] an American name. […] I think I fit in more with this American name. I do feel I have this dual identity with these two names. [My American name has] pretty much grown on me. My mom sometimes also calls me Colin. Yeah, I’m Colin now. I don’t have this desire to go back to my other name. I would just say I’m pretty used to it now.”

Simon Lee ’23 also said he felt accustomed to his American name because he has used it since preschool. He said his family, friends and classmates call him Simon, the Catholic name from his baptism. Nevertheless, he said his Korean name, Sang-hyun, leads teachers to squint and pause at their attendance sheets every year.

Lee said he feels that certain environments often force people to assimilate, regardless of their openness to doing so.

“There’s this subconscious thing where you have to adjust to what is comfortable for the people around you who [aren’t familiar with foreign cultures],” Lee said. “I don’t think any of my friends were like ‘you have to be 100% American, and you can’t be Korean.’ That didn’t happen, but [assimilation] was definitely something subconscious.”

Asemota said understanding how forced assimilation can be harmful is key to creating a more inclusive society.

“[I would like people to recognize] how damaging it is to always have to feel like you have to change a big part of your identity to feel accepted,” Asemota said.